Solving the problems of generative AI is everyone's responsibility

As we look to the near future of generative AI, we need to decide what we want to do with it

Welcome to the final part of Electric Nightmares, a short series about generative AI and games. So far we’ve seen the past, the present and the problems surrounding this new buzzword as it filters its way into our games and communities. In this final part of the series, I want to try and think concretely with you about what the future might hold; to go beyond what we think is just or legal, what we might be excited by or fearful of, and instead think about the practicalities of making and playing games today and how that might be impacted by generative AI's growing dominance.

What does it take for a new technology to take root in our lives? In the late 90s, two science policy researchers proposed that there are two things you need: comfort and credibility. Credibility is about how good the thing is, the desire to actually have it in the first place. Comfort is about how easily you can integrate into your life. We see this all the time in games. VR is a good example – there are a lot of great VR experiences, and the technology is unusual and exciting to many of us, but it’s tiring to use, disorienting, expensive, requires a lot of empty space and is still prone to accidents. It might be a lot of fun, but over a decade on from the beginnings of the Oculus Rift, VR still doesn’t really feel like it's found its feet. Other technologies have the opposite problem. NFTs actually became quite easy to use at their peak, and would’ve been quite easy to integrate into a lot of existing game stores - it’s just that no one cared. Every attempt to convince us that NFTs were going to add something to our gaming experiences floundered, and without that enthusiasm and excitement, it didn’t matter how easy or difficult it was to use.

Generative AI hasn’t really settled yet. Is it easy or difficult to use? In some ways, it’s quite easy. Sign up to Midjourney or ChatGPT for a few dollars and you can start typing in requests for content right now. But there’s no ownership over this technology, nor any indication of where it might go in the future, meaning you can’t easily rely on it to still be affordable this time next year, or even exist at all. In terms of credibility, look at the right press releases and you’d be forgiven for thinking AI could replace every human creator today. Yet every tool seems to work a little differently, and the mistakes we see range from funny to catastrophic. It’s no wonder that both AI’s supporters and detractors seem to feel uncertain about the present moment – the confusion of sales pitches, viral marketing, exposés and hands-on disappointments are all mixing together to leave us feeling completely lost.

Often with new games tech, it’s the quieter, smaller and more reliable systems that thrive in the long term. In his 2005 GDC talk, just before launching Spore, Will Wright spoke at length about what he saw as the power of procedural generation to solve the game design problems of the future, particularly the demand for larger quantities of high-quality content. Yet by and large, the solution companies found was to simply hire more people, and work them harder on bigger-budget productions. Procedural generation did break through to the industry eventually, but mostly in very specialised ways, in tools you may not have heard of or ever seen such as SpeedTree, a tool responsible for most of the video game forests you walk through. It worked because it was simple, specific and reliable.

We are beginning to see the first examples of generative AI tools that are more like this, such as Motorica. Motorica was born out of AI research at KTH, a university in Stockholm, and is now its own venture supported by Epic’s MegaGrant program. Their goal is to create a plug-in that can animate any 3D model in a variety of different styles, controlled through text input – so you can load in your big grumpy ogre that your 3D artist created, tell Motorica to animate it dancing a waltz, and you’re good to go. Motorica are building up their own databases of captured motion and gestures that they’ll have the full rights to both train on and license to game developers, with the aim of making “much of the work of a mocap-studio unnecessary”. Tools like Motorica aren’t free from the issues we’ve discussed throughout this series, especially if, say, you work at a mocap studio. But they may be free of enough issues to make their toolsets appealing to people who run publishers and developers, and that might be all that’s needed for generative AI to find a place in the industry.

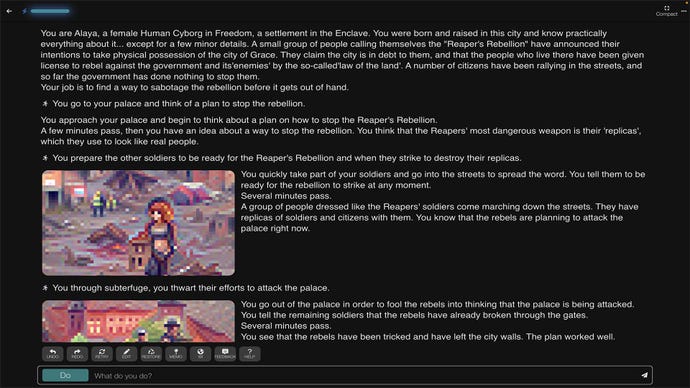

Ultimately, the best insight into what the future holds for AI in games might be right under our noses. In 2019, OpenAI launched GPT-2, and with it they opened up API access for people to build apps using it. Most of the prototypes people made weren’t very good, but two demos went viral: one showing that GPT-2 could write simple programs, which would eventually lead to GitHub’s Copilot programming assistant, and another demo by Nick Walton which let you play an interactive fiction game that GPT-2 wrote in real-time. This latter demo was very quickly spun off into a game called AI Dungeon, with its own website, a company, Latitude, to develop it, and updates that expanded its knowledge of genres and styles. AI Dungeon was lauded as the future of gaming - Walton was interviewed and spoke around the world, Latitude hired and grew, and AI Dungeon repeatedly popped up in papers and talks about games research, design and development. This showed not only that AI could change how games were made, but that it was in high demand and successful.

Today, AI Dungeon sits with Mixed reviews on Steam. Negative reviews complain about the poor quality of the writing, the system’s inability to understand the player, the aggressive subscription plan that locks users out of high-quality AI dungeon masters, and the restrictive filtering on messages and output. That last point is understandable though – AI Dungeon most likely had to intensify their moderation when it was revealed the tool was being used to generate graphically violent abuse fantasies, and that it often tended towards writing sexual content with minors seemingly of its own accord. AI Dungeon is a good demonstration of how the dream of a new AI product sours over time. Maintenance costs rise because running models is expensive (at its peak, Walton estimates that AI Dungeon paid $200,000 a month just to make queries to OpenAI). Moderations and restrictions must be built-in to account for rogue user activity and catastrophic mistakes by the system, and because of the inherent unpredictability of such large AI models. There’s anecdotal evidence that many of these models degrade over time as they are iteratively trained on user interactions, too.

That doesn’t mean generative AI is useless or doomed. I don’t even think it means it can’t be applied ethically. What it does mean, though, is that we should be careful when exciting press releases and viral GDC demos promise us the moon on a stick, and when the real costs of that new technology are hidden from us. Generative AI hasn’t quite yet proven its comfort or credibility to either game developers or players yet. It remains to be seen if it will suffer the same fate as VR or, worse, NFTs.

In 1950, Alan Turing wrote of AI (before the term AI was even coined), “We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done.” Turing was most likely thinking only about technical problems when he wrote that, but today I think it’s clear that the work we see ahead is the responsibility of all of us. As we’ve seen throughout this series, the answers to the problems we face lie outside of AI labs - they lie in courtrooms, in union negotiations, in investor pitch sessions and in fan-run Discord servers. AI researchers like myself are partly responsible for many of the problems we face today, but we are definitely not the only source of solutions. There won’t be a quick or easy answer to whatever issues we do end up facing in the video games industry going forward, but I do think there’s a path to be found toward a better future, if only we can work together to decide on where we want to go.