Visions Of The Future: Face-On With Oculus Rift

Next Stop: Holodeck

John Carmack is building the future. Well, technically, he's only helping this time. Along with Palmer Luckey and the other fine folks at Oculus Rift, Carmack's diving headset-first into the world of virtual reality. Of course, this isn't the first time gaming's tried taking Bambi-like first steps onto the Holodeck. But then the Virtual Boy happened, and everyone got really sad. Now, though, Carmack and co are claiming the tech's reached its threshold for “useful coolness,” and – after a hands/eyes/face-on demo with a duct-tape-and-hot-glue prototype of the Rift – I'm sold. This thing's the future. Or at least a big part of it, anyway.

Oculus Rift made me fear a ladder. I was trying my hand (and head) at Doom 3, and I'd climbed up one floor to flip a switch. Then it was time to go back down. Now, admittedly, I fear many things. Spiders, clowns, the fanbase of the Insane Clown Posse, those weird fish with the lights on their heads that live at the bottom of the ocean, the fact that humanity's supply of coffee is finite, social awkwardness, finding out that all my friends like Nickelback, etc. But gosh, heights are basically the worst. We are not birds, squirrels, or hovercrafts. Our feet were made for the ground, and that's where mine quite like to stay. So I approached Doom 3's ladder, glanced down it via the future magic of the unwieldy plastic box strapped to my face, and felt a deep-seated, instinctual tingle of fear slither down my spine. “This is high!” said my brain. “We could fall and bruise something and then die!”

These, of course, are not the concerns of BlastoBiff McSpaceMarine, granite-jawed hellpuncher. But in that moment, I couldn't help it. My mundane worries crept into a patently unreal setting because – on some subconscious level – my brain believed it was there. I mean, these events were unfolding right in front of my eyes, and if I moved my head, my field of vision shifted exactly as I expected it to. As far as my brain was concerned, I'd taken an abrupt vacation to demon-overrun outer space, and I was one wrong step away from certain, well, doom.

My multi-runged metal nemesis was just the beginning. When enemies moved in close to take a swipe at my most precious of visceras, I physically – as in, in the real world – took a step back. It was a bit strange, too, because only part of it was motivated by a fear of getting hit. The remainder, meanwhile, came from simple boundary issues. If someone gets that close to me in real life, I step away. They're in my bubble, after all. These demons were making bloodthirsty lunges right into my personal space. It was very rude of them.

So what, exactly, has changed since the days when virtual reality plummeted from its pie-in-the-sky space realm back down to earth in the most blood-curdling of fashions? Raw hardware muscle, mainly. To hear Carmack tell it (and admittedly, he might not be the most representative sample for mere mortals like ourselves), the headset itself is a relatively simple piece of tech. It does, however, require a massive amount of resources to render stereoscopic 3D at a high level of graphical quality, and we're finally hitting the point where that's very feasible.

Granted, the Rift is still far from ready for primetime. For one, the graphics were still fairly blurry – and it becomes all the more noticeable when they're centimeters away from your eyes, doing their damndest to give your eyelashes some strange new breed of bedhead. Also, more pressingly, the control system still leaves a lot to be desired. For the purposes of this demo, I used an Xbox 360 pad (hisssssssssssss [flesh begins sizzling]), with the left stick only in control of the gun's position – not my field of vision. The right stick, meanwhile, took care of movement just like always. In practice, this setup was functional, but clunky. Sure, I sent hell's minion's packing all the same, but it never felt particularly natural or intuitive. Instead, the appeal was in simply being there. Looking around with my own neck and nearly stumbling over couches while John Carmack (note: sold separately) snickered to himself and probably read my mind because I bet he can do that.

These problems are, however, not insurmountable. In fact, according to Carmack, most of them will be ironed out in the very near future. Blur-o-vision, for instance, will disappear with higher-res screens, which Carmack and co are working on getting into a new prototype right now. As for controls, he suggests the Razer Hydra or even something like Kinect could provide a much better fit. At that point, however, a total lack of feedback becomes a problem of immersion-killing magnitude (think: punching someone's face in-game, only to send your fist sailing right through air – and nothing else). But on that front, Carmack's already dreamed up quite a few potential solutions. And only some of them might be fatal!

“[There are possibilities like] Galvanic nerve stimulation,” he told me, “where you can put these electrodes on your head and send currents through your brain, and it makes you feel like you're going different directions on there. And if it felt like you were moving when you pressed the joystick or when someone hit you in the game, that'd be really powerful. But, well, there was some sense of scarring on the inner ear of people who've used that technology,” he added, laughing a bit nervously.

“There's a guy that made a flack jacket with a bunch of thumpers in it for FPSes several years ago. We could have that integrated in.”

In the near term, though, Carmack's more focused on perfecting the central device. Specifically, he's hoping to add a 120hz OLED panel to make graphics sharper and – here's the interesting part – some form of position tracker (for instance, cameras on the outside of the Rift) to track users' arm/leg movements and simulate them in-game. Optical tracking – that is, tech that follows individual eye movements – is also on the list, though Carmack's not 100 percent on it just yet. “I'm confident that optical tracking is possible with new stuff, but I'm not entirely sure. But a lot of the stuff is more 'I'm positive we can make this happen,'” he noted.

The hope, then, is that we'll see the Rift make a serious splash before too much longer. “It'll be our secret weapon for Doom 4 showings,” he explained, quite visibly excited. But the potential here goes far, far beyond first-person shooters about BFGs, cyberdemons, and mortal man's most dangerous threat of all, the ladder. Carmack's hoping to garner interest from every developer under the sun, and he's quite hopeful that even non-first-person genres will benefit in a big way. “As I see more and more the value of having the headtracking on this, I realize practically anything would benefit from this immersion,” he said. “I've looked at god games, and it is a better experience.” Meanwhile, I suggested some form of Mirror's Edge spin-off and a game with no action component – one that simply focuses on looking and the awkwardness a lingering stare creates – and he nodded vigorously in agreement.

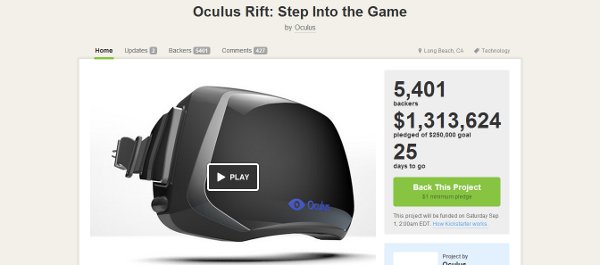

For now, though, Oculus Rift is an amorphous blob of potential just waiting for someone to shape it. And with an absurdly successful Kickstarter putting plenty of wind in its sails, it seems almost guaranteed to go far. Put simply, I'm excited. Incredibly excited. Games have been chasing the holy grail that is “immersion” for eons, but this stands to be one giant leap from the stone age to reaching out and touching the stars – or at least feeling like we can, anyway. Back in the day, everyone from developers to sci-fi novelists dreamed of this sort of thing. Now, claims Carmack, the day's finally arrived for virtual reality to be, well, a reality.

“Now that all of this is happening,” he concluded, “the dreamers can come back out. It'll be the creative market again.”