The eeriest places in games are the ones where the environment is the monster

There's something behind you

Whilst raw forms of horror work through shock and disgust, the eerie is felt more as a threat. Perhaps something seems to hover over or follow you -- there’s a rustling just behind you, or a shimmering in your peripheral vision. Usually eeriness pertains to places rather than people. Places that seem to move, shift or even act when they really should lie still. This sense is just as likely to be found in an empty room as an open moor. Sometimes, however, this sense manifests, becoming a force that can reach out and grip us.

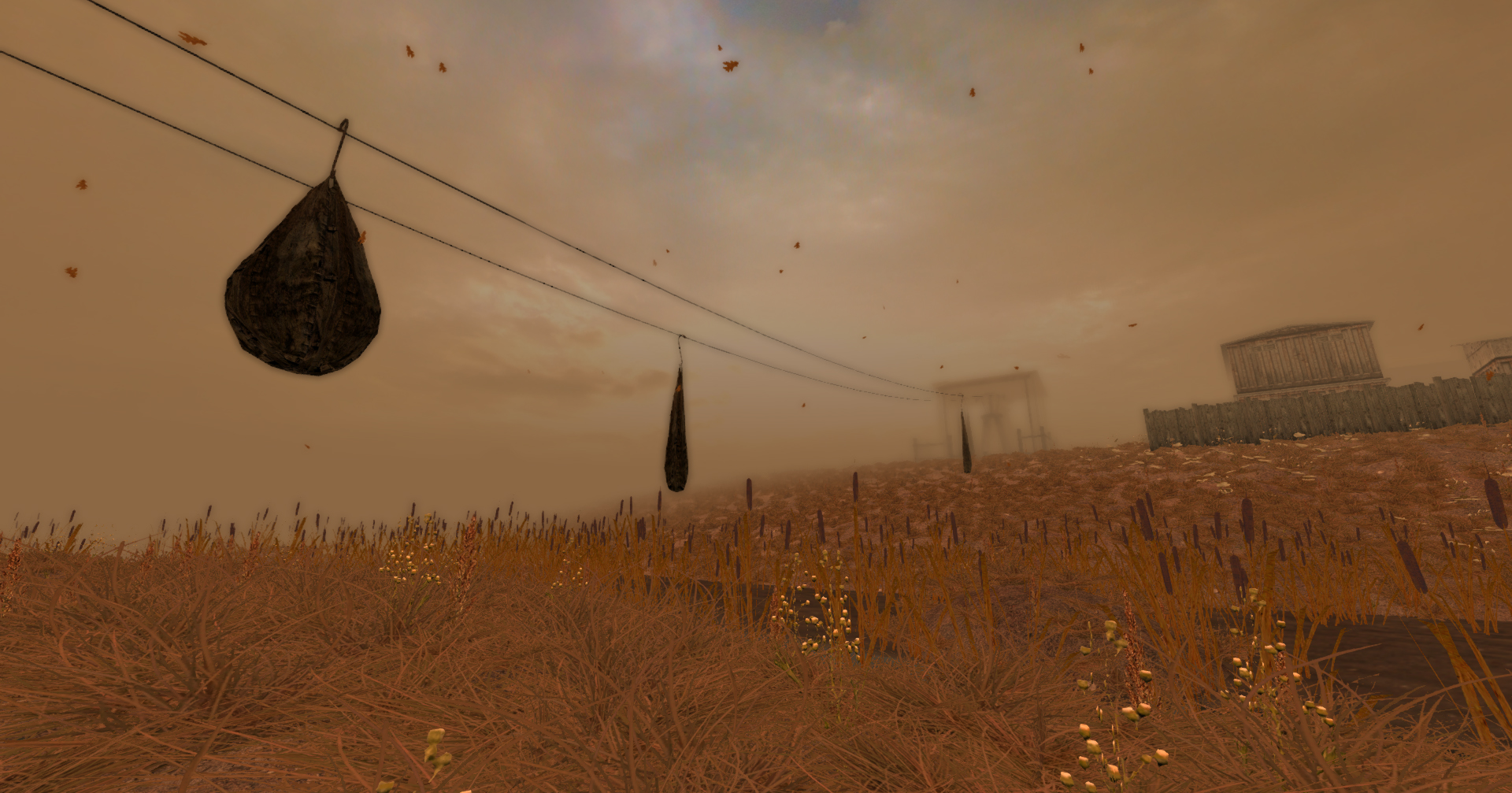

There are pockets of land in The Zone that feel like the quietest place on Earth. Still, empty and faintly haunted, the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. series’ setting is a fictionalised version of Ukraine’s Zone of Alienation. A containment field set up around the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant following several disasters, your presence there is an intrusion into a quintessential no-go zone.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. presents a landscape of blasted heaths, gnarled trees and bogs — the kind of unhallowed ground you’d expect witches to convene on. Its grey skies and dreary weather, its atmosphere and place, are what makes this game so special. It has the ability to establish a universal eeriness through its environment alone.

Whilst eeriness forms around natural landscapes where unknown things seem to blow and whistle in the air, S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is only a partial wilderness. Many of its environments are contrastingly artificial. The crumbling factories, plants and facilities are the real artifacts of Chernobyl.

These relics of an industrial past highlight an act of disappearance. According to the writer and cultural theorist Mark Fisher, it is these kinds of ruined spaces, “emptied of the human”, that create a sense of eeriness. Even minor places in S.T.A.L.K.E.R., like the “vast machinery graveyard” with its piled-up catastrophes, or Cordon’s abandoned bus stop and concrete underpass, gesture towards a kind of failed state. We live in an era where post-industrial wrecks are a lingering presence. For every nuclear disaster there are a thousand economic ones. According to Fisher, this kind of eeriness revolves around the question: “Why is there nothing here when there should be something?”

But there is another kind of eeriness alive in The Zone. A constant feeling that something watches you — something which does not belong. Whilst the land is visibly marked by an absence of the human, there also exists an unusual presence that prompts us to ask Fisher’s first question in reverse: “Why is there something here when there should be nothing?”.

There’s more to The Zone than first appears. Think of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, where it gradually becomes clear that something is askew in the isolated village, culminating in the local birds attacking humans in a show of force that can’t be rationalised. Between S.T.A.L.K.E.R.’s ghost towns and hollowed factories there exists a similar non-human entity.

The Zone makes itself known through anomalies of various shapes. The first anomalies you discover in the game are distortions, gravitational vortices that ripple in the atmosphere and can pull you in and damage you. The second is residual radiation. You’re equipped with both a built-in geiger counter and an anomaly detector. Their clicks and high-frequency beeps alert you to hidden presences. Together, they create the perception of a land possessed — a cloaked agency which should not exist, as well as a dark ecology that works beneath the world as we commonly perceive it.

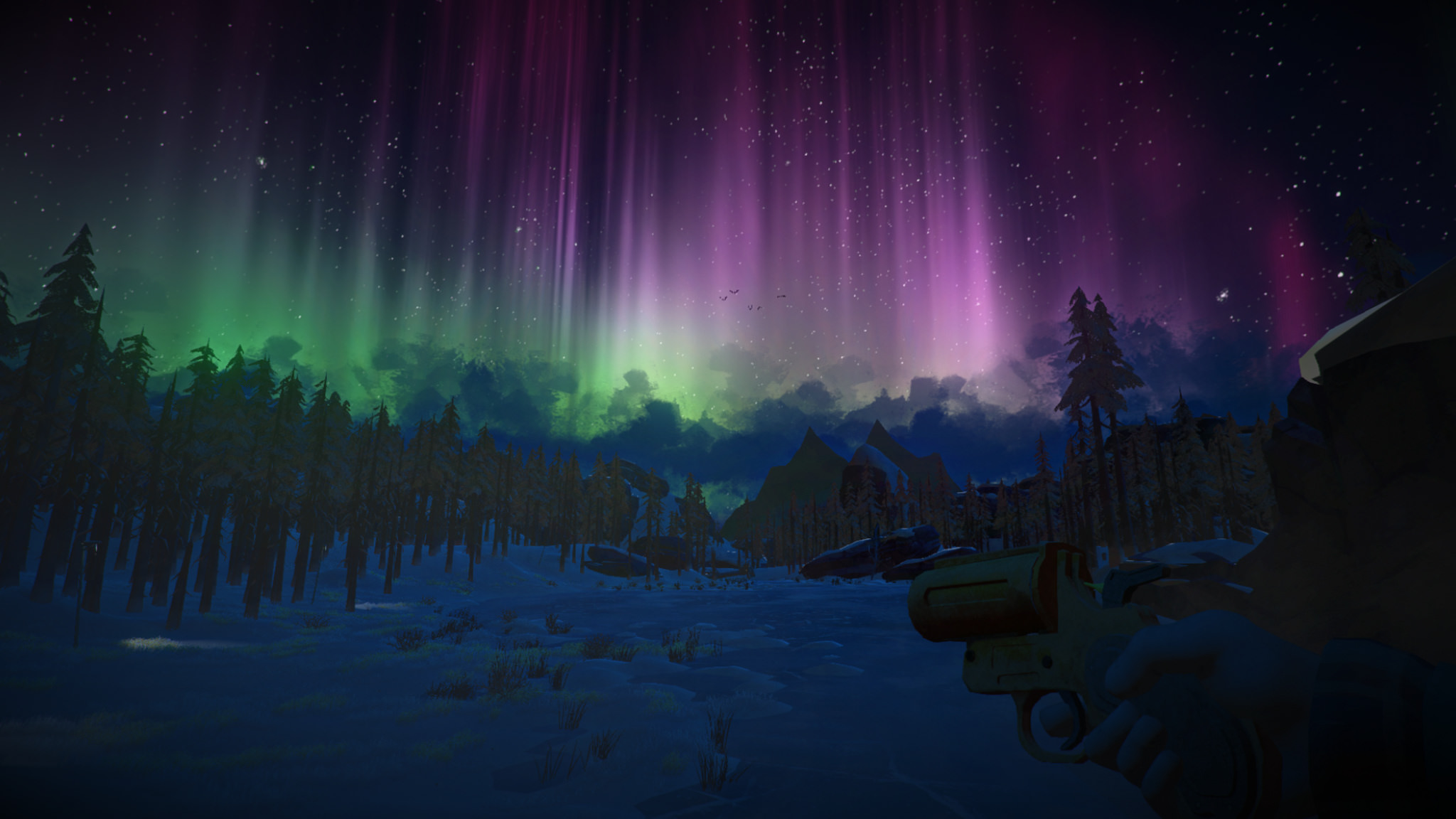

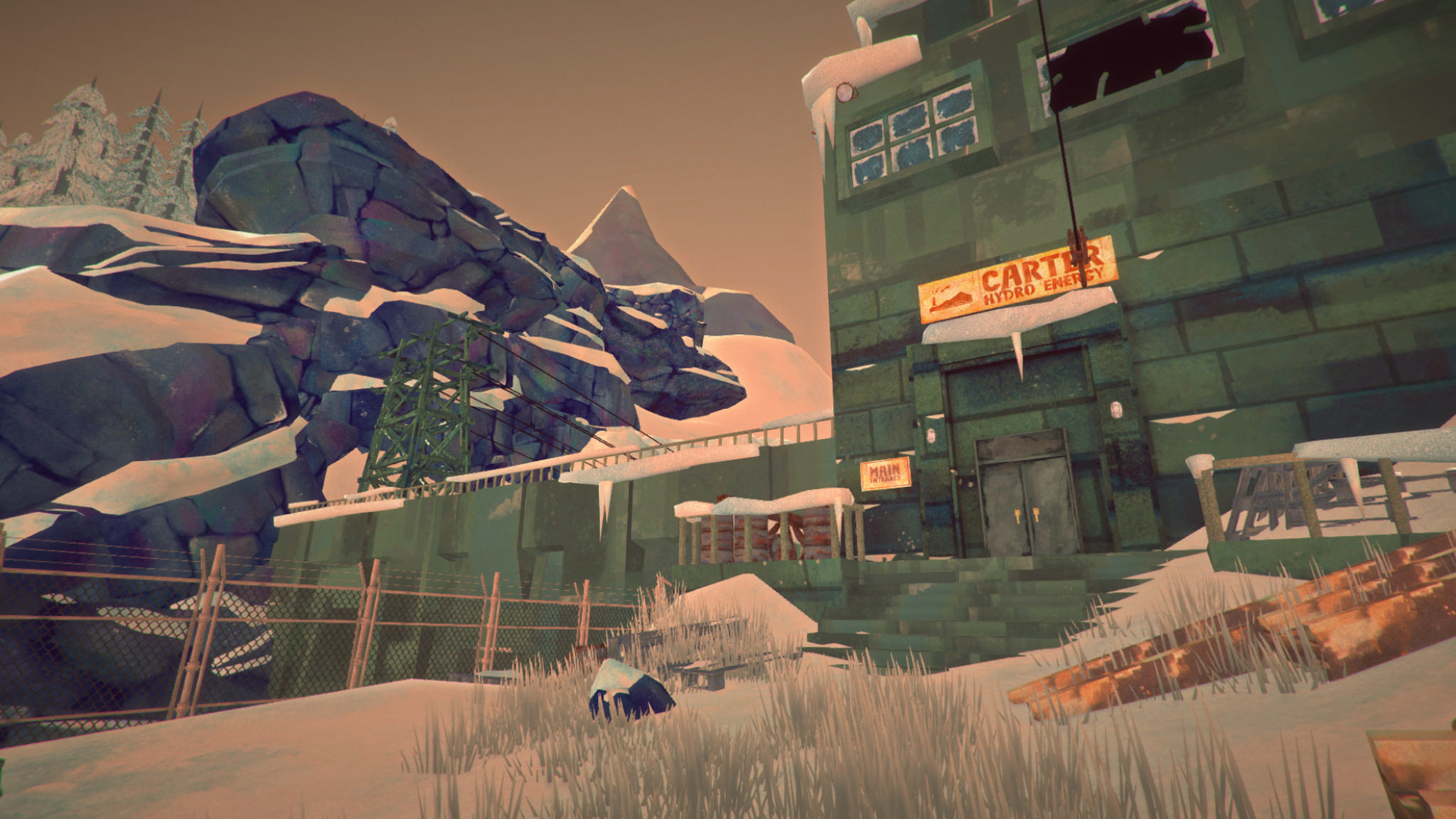

The Long Dark’s Canadian wilderness is another eerie environment. Its Quiet Apocalypse was caused by an Aurora which flared up and destroyed the world’s technology. Dotting its world are signs of disappearance — an abandoned whaling facility, a deserted town, an old dam.

The Long Dark’s creative director, Raphael van Lierop, spoke to me about the world he’s created. “The very rules of physics have changed. Not only does electricity not work the way you expect, but everything is slightly broken. The natural environment is tainted and in some ways has become hostile to human existence. This is a terribly frightening prospect, all too real for us right now if you paid attention to the recent UN environmental report.”

For van Lierop civilisation is a “thin veneer”, a comfort blanket that can easily be ripped apart by natural phenomena. This communicates a kind of ecological horror. Nature is larger than us, and it can destroy what we’ve built.

To create an eerie mood it’s important to put the weird and mysterious back into nature. Think of the sound of radiation or the hum of an empty landscape, noises we don’t ordinarily consider natural. van Lierop describes the importance of these abnormal sounds. “The creaks and groans of pipes and metal shifting. Small rocks tumbling from a mine shaft ceiling. The wind rattling a window pane,” all work to create an atmosphere where, he says, players feel surrounded by a vast and uncaring environment. But there’s also the implication that places have a more personal history. van Lierop told me that things like a hastily abandoned dinner table or a children's swing-set can anchor you to the world, whilst highlighting the sense of sudden abandonment.

The Long Dark’s wilderness is not unlike the invisible presence seen in S.T.A.L.K.E.R.. “I think you can draw a very strong connection between our Aurora and the notion of a Zone,” says van Lierop, “a zone being an environment and ecosystem that has been thrown out of balance due to some unforeseen external influence.”

Whilst The Long Dark’s Aurora is yet to be fully explained, we can see in it Mark Fisher’s concept of a presence where there should be none. van Lierop tells me he always talks about the Aurora as if it's a sentient thing. “It moves like it has purpose. Electrical things are animated in its presence.” Empty landscapes are eerie, abandoned homes too, but it is the unnatural presence of the Aurora, and the terror that it might unleash, that’s so critical to creating a sense of eeriness.

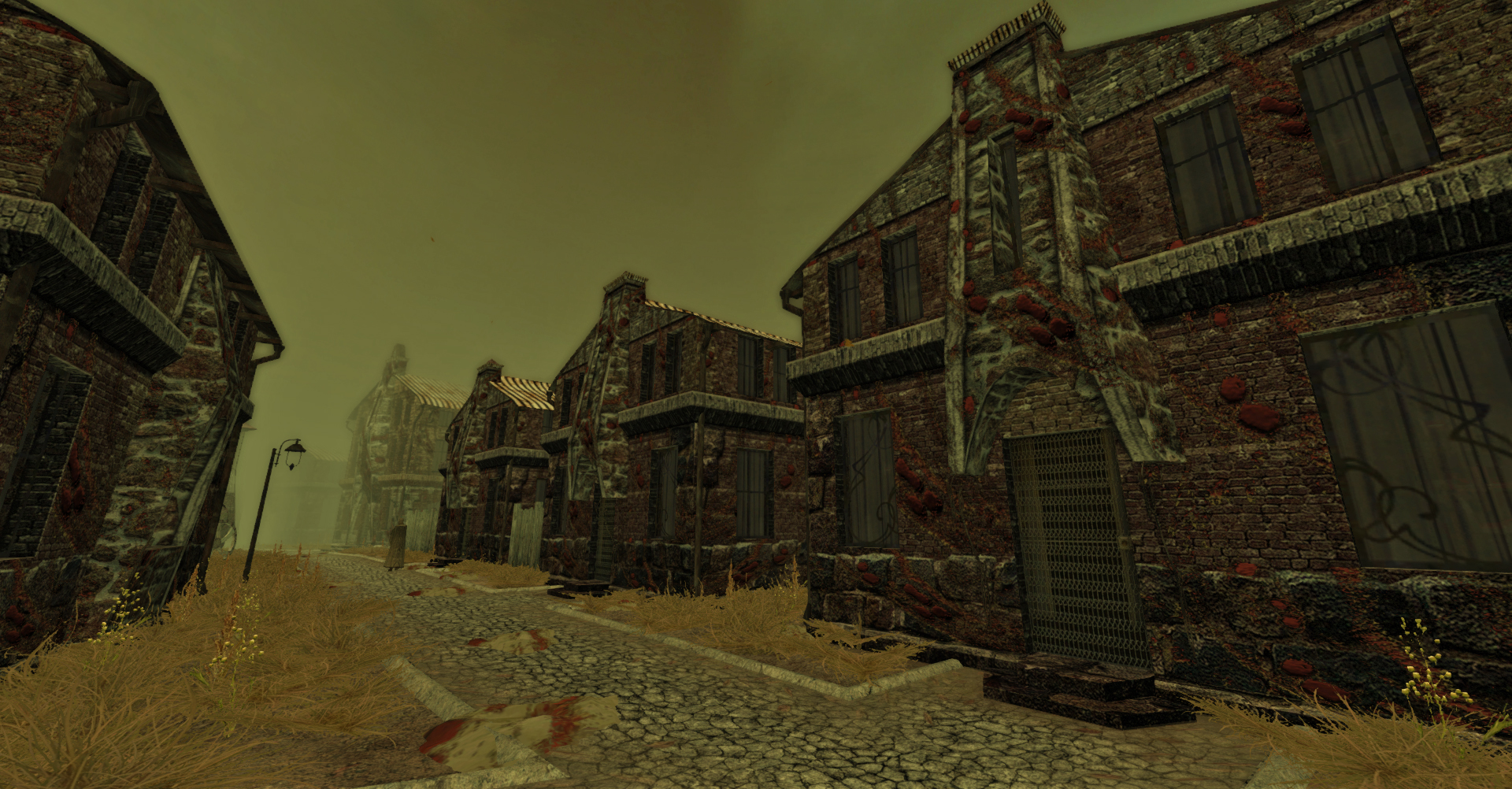

There’s no better example of eeriness than Ice-Pick Lodge’s Pathologic. The game is set in a place called The Town, a remote settlement situated in the Steppes. The culture there revolves entirely around a meat-processing industry, with strange traditions having developed out of this. The game’s natural landscape is incredibly atmospheric; the Steppes are harsh and exposed, a place where even the stoutest trees have been blasted out of existence and a muddy pall hangs over it all.

In contrast to the sacred soil is The Town’s meat industry. In the Abattoir butchers pour the blood of Bulls into underground cavities, soaking the earth in gore. Whilst the machinery of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. and The Long Dark have ceased, Pathologic’s Town is an industry in decline — there are vacant factories, locked warehouses and old facilities, but The Town is dying gradually rather than being already dead.

Pathologic is unique in that it isn’t just a snapshot of an abandoned place, but a 12-day process of disappearance. Over the course of the game The Town is slowly poisoned, ravaged by an eerie entity known as the Sand Plague. This is the game’s chief antagonist — an invisible darkness that floats in the air, occasionally forming into clouds of bacteria that swarm towards you. The game describes the plague as “a monster with no face”, a thing with “a mind of its own, as if driven by some irrepressible will.”

As districts of The Town become infected the plague manifests through boils and pustules on the buildings. The Sand Plague may be immaterial, but there is a real eeriness to its activity. This isn’t just the agency of a microorganism, things that are alive and possess biological impulses. The Plague is more than that — a sentient agent and conscious evil. We are once again confronted with the existence of a presence where there should be none.

Since 2005 Pathologic has only become more relevant. The link between The Town’s unsustainable animal slaughter industry and the Sand Plague is explicit. Pestilence is the environment rising up and striking back at us. In this sense Pathologic, The Long Dark and S.T.A.L.K.E.R. are each an example of ecological horror. The natural land, polluted and ravaged by human disaster, finds a way to strike back. Nature has twisted and become strangely animated. This also makes these games an antidote to anthropocentrism. Our species and its activities are dwarfed by the non-human forces which surround and permeate us. By natural law The Zone, the Canadian wilderness and The Town should lie empty and still, and yet in each of these places we feel that eerie presence, one that stirs deceptively but powerfully beneath the surface.