The Flare Path: Row Boats

Meet Mare Nostrum

Mare Nostrum, the galley warfare wargame currently in production at Turnopia, shouldn't have any trouble eclipsing the competition. To my knowledge, in the forty or so years since home computing and tactical gaming first cuddled up, ancient naval aggro has inspired only one title and that title is probably best forgotten.

Short on subtlety, scope, spectacle and syllables, the best things about RAM! (Avalon Hill, 1984) were the box cover and the animated oars on the title screen.

Like RAM!'s creator, the man behind Mare Nostrum dabbled with chariots before moving on to biremes and triremes. Qvadriga was well received in these parts and proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that Turnopia (Daniel López Soria) understands the difference between 'simple' and 'simplistic' and knows how to balance chance and choice for maximum fun. Even if I didn't have the reassuringly lean and focused Mare Nostrum design doc open in front of me, I'd be confident the PC's first dedicated galley wargame in thirty years was in safe hands.

(All screenshots show a development build. Graphics and GUI are work-in-progress)

Encompassing five centuries of Mediterranean fleet clashes and featuring fourteen different ship types, the hex-hiding Mare Nostrum inherits a couple of concepts that served Qvadriga admirably. Convinced that traditional IGOUGO turn structures and antique wet warfare aren't good bedfellows, Daniel is once again utilizing a simultaneous order execution system. The fatigue fixation returns too.

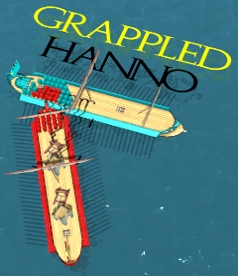

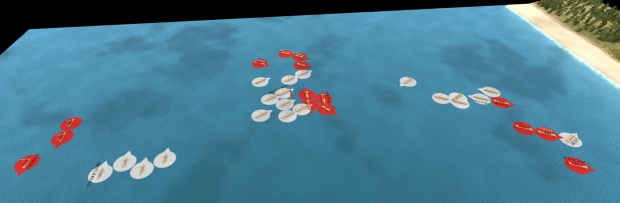

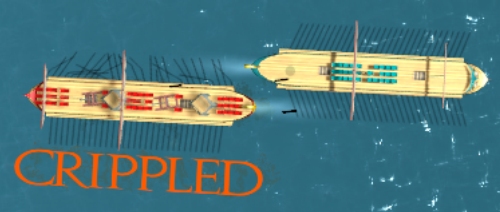

WEGO means both sides - human and AI, or human and human in the case of multiplayer - will be issuing orders based on assumptions. If that enemy quadrireme maintains its heading and speed, my trireme should be able to ram it amidships by darting between those two crippled biremes and making for that hex. ... If that septireme is about to do what I think it's about to do, a ship sent to this hex with a grapple order should spoil its plans. Inevitably some assumptions will turn out to be erroneous - chaos and calamity will regularly interject, scattering tidy formations and shivering inflexible plans.

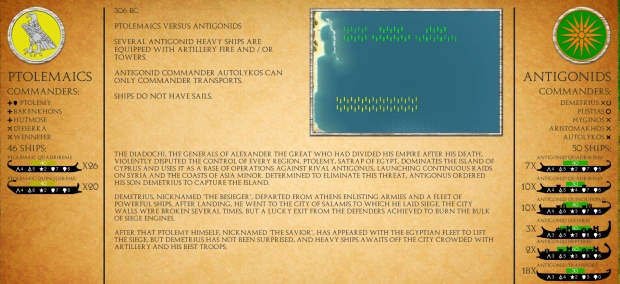

In Qvadriga there was a deliciously fine line between running horses hard and running them ragged. The design doc suggests player-admirals will face similarly tough speed-related choices in MN. All ships have an X-hexes-per-turn cruising speed (the number by the first arrowhead icon in the above pic) and a faster max speed (the number by the second arrowhead icon. Other icons show seamanship skill, hull strength, ram attack effectiveness, and – the figure in the red box – the number of missile-slinging 'marines' on board). Using top speed is tempting but risky as it can, depending on the result of a check roll, generate weariness that prevents similar spurts until oarsmen have rested.

Naturally, wind speed and direction also influences vessel velocity. Craft with unfurled sails are more vulnerable to fire damage and less nimble in ramming/grappling situations, but in situations where you need an extra knot or two those might be risks worth taking.

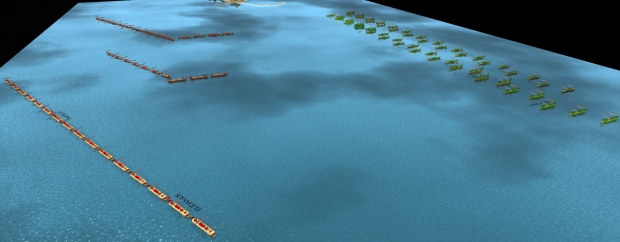

If the galley count in the above image alarms your inner loafer, reassure them with the following info. Although control of individual ships is possible, a squadron system should allow large formations to be moved around and engaged and disengaged with relative ease. Certain vessels will have named, trait-blessed bigwigs aboard and these will act as follow-my-lead flagships for nearby craft. Issue one order and multiple ships respond. Stragglers beyond command range (more than four hexes from a commander and unadjacent to an in-command ship) are temporarily controlled by a friendly AI who will endeavour to return them to the fold.

Defined by their core stats and by additional equipment such as towers, catapults and corvi, ships can be captured and crippled as well as sunk by rams and set ablaze by Greek fire. A ramming manoeuvre in which the rammer is moving in the same or opposite direction as the ramee when contact is made, is interpreted as an attempt to 'rake oars' rather than puncture hull planks. If successful the victim is left with useless splintered oar stubs on one side. A second successful attack completes the immobilization.

Picturing a briny battlefield combed by influential breezes and dotted with ships that could be disabled, entangled, on fire, out of command, or on potential collision courses with friendlies, an obvious question springs to mind. Will the AI cope? Daniel admits MN is far more complex in this respect than Qvadriga, yet seems to be confident he'll deliver capable/competent adversaries. Describing how the AI operates, he highlights the squadron system (flagships guiding surrounding vessels) as a key behavioural building block.

“The first objective for both the AI and the player is that no ship is out of command. After this, every AI commander decides in general terms what his group should do – whether they should approach or move away from nearby enemies, move forwards or backwards and the average speed to follow, if they should go ramming and raking or try to grapple and board... Once all of this has been decided, each ship under his command tries to conform to the plan according to its particular situation.”

The total lack of Fog-of-War should make the AI's job easier. Daniel justifies this design choice by pointing out that most naval battles of the time took place in fine weather, close to coastlines, with both sides “presenting full force from the beginning to cause the greatest initial impact”. The exceptions, scraps like Drepanum and the Battle of Ebro River, will be modelled with the aid of special rules designed to reflect the disorganisation of surprised fleets.

In addition to a powerful skirmish generator, the fruits of which can be enjoyed in both single and multiplayer, Mare Nostrum will boast 24 historical and semi-historical battles plucked from nine wars (Colonial Wars, Greco-Persian Wars, Peloponnesian War, War of the Diadochi, First Punic War, Second Punic War, Syrian War, Pirate Cleansing, Rome Civil Wars). “The oldest battle is Alalia, where the main seafaring powers at the dawn of history - Greece, Carthage and Etruria - confronted each other. The most modern is Actium, where Octavian and his brilliant strategist Agrippa defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra, ending the civil wars of the republic.”

Explaining the absence of traditional wargame campaigns Daniel cites history. “I decided not to create campaigns because during the period each battle was a decisive event that ended a conflict. Even the most powerful defeated empires needed several years to reassemble a fleet to face the enemy again. The First Punic War could be an example of a campaign, but there were only five naval battles during 23 years, and even then the same commanders and admirals weren't present in each battle.”. My instinct says this is one of those situations where history should probably doff its cap to fun, but who knows, MN may not need a battle-binding campaign system (I'm visualising something piratical and dynamic) for long-term appeal.

You may well be in a position to assess MN's potential longevity before I am. Turnopia and Slitherine are looking to recruit 15-20 Flare Path readers as 'closed beta' testers. Anyone willing to play the pictured development build and provide feedback on everything from ergonomy to AI should contact me using the email address at the top of this piece and I'll forward your details. You don't need to be a Trireme or a War Galley fan to apply (two board games mentioned by Daniel as inspirations for MN), but, obviously, a genuine interest in warships with bronze beaks and wooden cilia would be advantageous.

* * *