The RPG Scrollbars: Questing at the speed of light

In space, nobody can hear your bias

This week, something a little different. I'm going to talk about something I'm working on myself. Obviously, this brings with it certain complications. I'm won't pretend not to be biased, though I don't mean this to be an advert. I just thought it would be interesting to share some of what I've been working on as the writer and co-quest designer of Daedalic Studio West's The Long Journey Home [official site], and to dig in to the difficulties and decisions that underpin the making of RPG quests.

Got the disclaimer? Cool. Filter accordingly as we blast off. Next week, back to other games and/or long rants about where my bloody Witcher 3 action figures are.

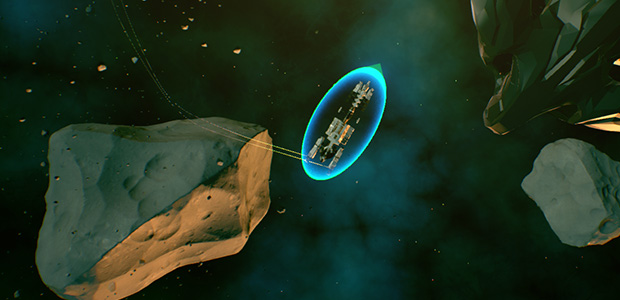

First, quick summary time! The Long Journey Home is a mix of space RPG and roguelike, heavily inspired by classic space games ranging from Star Control 2 to Starflight to FTL, to really obscure stuff like Psi-5 Trading Company.

Starflight and Star Control 2 are the biggest touchpoints though, and just to get the obvious question out of the way, I know that Stardock is making an official new Star Control game, but aside from having seen the couple of screenshots that came out the other month, all I know about it is that I'm really looking forward to playing it next year. Always been a fan of GalCiv and the company's sense of humour is a great fit for the license. Fingers crossed, fans will enjoy both games, which are going to be pretty different.

Anyhoo, the basic premise. You're in charge of Earth's first jump capable ship, on what's mostly a PR exercise for space agency IASA to rekindle the public's interest in space travel. With a crew of misfit experts ranging from an archaeologist to an embedded blogger, your job is to make a quick, easy jump to Alpha Centauri and back. Shocking literally nobody, it goes horribly wrong. The crew is stranded at the far end of the galaxy, alone, injured and deeply unprepared. The only way back is through.

One of the interesting things about quest design is how every RPG has its own distinct flavour, based on everything from the player's purpose to the nature of their avatar to the technology level of the world. They often have similarities, obviously, but most have at least some unique aspect that changes them up. Take quest givers. Individual person, automatic delivery, bulletin board system, hub? And then when you've done the quest, how do you turn it in? The classic approach is that you go back to the person who gave it to you, since in most cases that's the most 'realistic' way of handling things. The Secret World however, to give one example, is a world where everyone has a phone, so it makes much more sense to report in from the field. World of Warcraft also slowly moved towards just making NPCs able to beam psychic messages to you, in one of many 'just go along with it' decisions over the years that stem from players typically and LOUDLY favouring efficiency over in-world consistency.

And that's just a tiny part of questing fundamentals. What verbs does the player have access to? Verbs in this case being anything from cooling a fire with an ice spell to just clicking on a thing. What's their status in the world, since that will determine both what's worth their time and what people will charge them with. What bigger picture are the quests in service of? If you're a travelling hero, it makes sense to be picking up odd jobs. If, again, you're a member of the Illuminati charged with protecting the world from hordes of evil from behind the veil, you can't really be caught in the river, just fishing, just as if you're in a race against time, you're probably not going to stop to help get someone's cat out of a tree. If something is an MMO, how many players will be present at once, and can that be justified? Is the challenge level fitting for the level of character it's being given, on both ends of the scale? Does your setting allow for or demand comedy/humour, or is it all being played straight? Does the engine have the power to show interesting things happening, or will all the cool stuff just be described to the player in a "Wow, that was an amazing explosion! I could see it from here!"

In short, it's not enough to just throw everything at the wall and see what sticks. Like the old saying 'never apply a Star Trek solution to a Babylon 5 problem', every RPG is unique. Even if you are just killing twenty rats and gathering bear asses.

Though thankfully, we don't have space rats to deal with. Just some bare asses.

Here's a few specific challenges we had early on with The Long Journey Home. First, and most importantly, the game is built on forward momentum. The universe is broken into systems, connected by Gates. Your job is to get Home. This alone is a massive deal for questing. We can't send the player back to somewhere they've been. We can't have them stick around too long in any one place. We can't show much in the way of change on a local level, though there are a few exceptions to that, like accidentally infesting a planet with a destructive alien swarm. Or nuking it.

Second. The crew is alone and desperate. The player shouldn't be thinking "Why don't they just live with the Wolphax Knights," or similar, because that diminishes the goal of getting Home. As much as we want the quests to be exciting and the universe fun to explore, as much of the game is rooted in the idea of homesickness and longing, especially in the crew's banter and internal thoughts during the voyage.

Third. The crew is vulnerable. Any empire in the game could sweep in and crush them. However, their isolation is also felt in things like not having long-distance communication, not having bulletin boards for quests, etc. The one big exception we ended up making to this rule was that the first time you get credits, you get a generic bank account, though the original idea was that everything would be trade based. It was cool, but it was also a real pain in the neck, so in the end, credits won out.

Fourth. A ship doesn't have many verbs available to it. Scan. Shoot. Communicate. Orbit. Salvage. Send down Lander. Fly away really, really fast. Not many more.

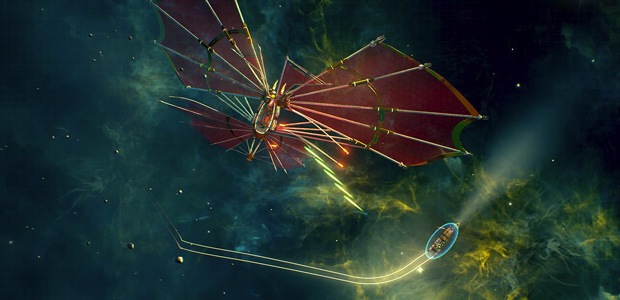

Fifth. Galactically speaking, nobody cares about or respects the crew. At best, you meet polite well-wishers. At worst, pirates and slavers who are quite happy to rip you to pieces and condemn their new human slaves to a lifetime at the bottom of a cobalt mine. Quests have to be interesting and feel worthy, obviously, but it wouldn't make sense for everyone to expect you to solve all of their problems for them.

All of those are wrapped in a final, global pillar, that wherever possible, The Long Journey Home should offer the choices and opportunities that you'd actually have if you were there - including the freedom to break or ignore every quest, to make whatever friends or enemies you want, and make the most of your crew's abilities to solve problems. There's an old RPG saying 'if you stat it, they will kill it', usually used as a warning. Here, go right ahead. It's a phenomenal scripting pain in multiple arses, but all to the best. If a ship comes up and asks you to do something, and you just shoot it, that's a valid choice. Indeed, it can be a sensible one, especially when dealing with a mugger, or a ship trying to persuade you to take on infested goods. (But if you do, please, take a moment to think about the poor coders looking for edge-cases...)

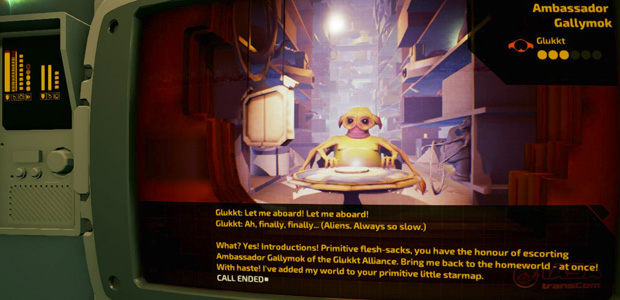

The cool thing about restrictions though is that they breed interesting ideas. For example, just because nobody's going to ask you to find the lost treasure of their people doesn't mean that you can't do that, and face interesting situations because of that. Will they be glad to see it returned, or furious that some mere aliens are waltzing around with their equivalent of the Holy Grail? Likewise, not being able to send the player back to hand in quests or handle debriefing by e-mails or whatever lead to having to bring quest-givers back to the player. This really helps boost the feel of a living universe, and makes betraying someone feel much more personal.

(And oh, can you betray them. In an early quest for the Wolphax, a race of grasshopper style guys who like to play as glorious knights, you're approached by a lowly squire to kidnap his beloved so that he can rescue her from the 'evil aliens'. Another race will ask you to run important deliveries for them. But if you want to sell her to the slaver race and just open the box and keep what's inside, you go right ahead. Of course, there are always consequences, but if you think you can handle them, hey, it's your ship...)

My favourite solutions to the problems though involve handling the verb problem. Enter the crew. A lot of space games treat the crew as little more than stats, while we wanted them to be both characters the player could feel for, and valuable parts of the mission. There are ten in total, of which you get four per game. Gather 'artifacts', go into the lab, and each will attempt to use their specialist knowledge to do something with it. The archeologist for instance, Siobhan, might take an old relic and be able to translate it. The researcher, Nikolay, might realise it's a gun. Someone else might just break it.

Where things get interesting though is that we get to use these verbs to both offer abilities, and explore their characters. I said above for instance that if you're on a courier quest, you can open the boxes. That's true, but only if you have a crewmember willing to do so. If everyone's a goodie-two-shoes type, you can't force it. (You're not one of them, or the Captain, per se, but more the 'spirit of the crew'). This extends to dedicated 'Crew Picker Quests', where someone has to volunteer for something. Usually, it's something horrible, like an alien torture probe designed to determine guilt through trial by ordeal, or agreeing to become a slave so that the others can go free. This whole system ultimately came from that problem that a ship can't actually do much, and our characters who could... well, didn't. After a couple of experiments on one of the game's silliest quests, though, being able to bring them in via multiple vectors evolved from a cute feature to one of my favourite pillars of the experience.

Another unique challenge for space games of course is handling the aliens. Aliens are really hard. If they're too familiar, they're just people with silly foreheads. If they're too crazy, finding actual 'game' involving them becomes a nightmare. Do not get me wrong here. I love and revere and respect and would consider wrapping Star Control 2 in fur so that I could better cuddle it, but this is something that it did kinda cheat with. Its concepts were amazing, but in practice most alien encounters consisted of a really long conversation where they got to tell you all of this crazy stuff that wasn't particularly shown once in game. There's exceptions, of course. Many are genius. The Ur-Quan Civil War and their philosophies, which extend to being willing to talk properly. The Dynarri influence. The Spathi ships being psychologically perfect. But in most cases - most - the aliens didn't actually do a whole lot of weird stuff except talk about how weird they were and hand over their ships. We needed ours to be more active.

In designing ours then, we took more of a 'hat' approach to things. You have your military focused race, you have your religious race, you have your space pirates and so on. It was necessary, partly because you only get four of the major races in any one playthrough, and because the quests ultimately needed a ground-level of familiarity. We came up with some really crazy aliens early on, but there's just not all that much you can do with, say, an inflating sac that ultimately evolves into a space whale. Not that would feel unique to an inflating sac that evolves into a space whale, that is, rather than just a slightly dressed up FedEx quest to deliver ambergris or whatever.

Instead the focus went on trying to give the different creatures depth so that the player sees different sides of them through their quests, through conversations with friends and enemies, through individual encounters, and so on. The trader race for instance, the Glukkt, may initially come across as being completely amoral, but no, they have a sense of honour and draw a line between good business and foul play. The Wolphax, the military race, are the exact opposite of your Klingons or whatever in that physically they're pathetically weak insects, with their current love of battle stemming from the fact that nobody cares how tough you personally are when you've got ray-guns.

Most of the races haven't been officially announced yet, but again, in quest design, a big part of the process was figuring out ways of not just presenting their hats, but playing with them a little bit. The dialogue system for the game for instance can track both what you say and what you do. Much like the Minbari of Babylon 5, some aliens take it as a compliment if you approach them with weapons raised, since it shows respect. Others take umbrage at the threatening action. Part of the fun is learning everyone's quirks and making the most of them - including what they'll take if you lose a fight. Borrowing from games like Risen, most of the galaxy doesn't actually want to fight to the death unless really pushed, though that doesn't mean they won't, say, demand one of your crew to let the others continue their voyage.

Now, obviously, how well we've done with all this of course remains to be seen. Fingers crossed. Either way, The Long Journey Home is due out next March/April, with both updates and weekly in-universe newsletters mostly coming out over on Facebook. For now, hopefully this has been a interesting look behind the scenes of what I've been working on this year and the thought processes that it's easy to overlook in favour of just ploughing through, or choosing to do a cheap gag about instead of focusing. Unrelated, next week: How Tyranny is the new test of intellectualism.

I kid, I kid. And can't wait to play it. After another billion words of alien dialogue.