Heavily Engaged: On Wargaming, Guilt And Remembrance

From The Archive

Every Sunday, we reach deep into Rock, Paper, Shotgun's 141-year history to pull out one of the best moments from the archive. This week, Tim Stone's piece on grognard guilt, originally published in 2011.

No battle reportage this week. Rather than confuse you with another tale of how Easy Company went east then north a bit then left a bit while Baker Company went west then south then right a bit, I thought I'd try to get to the bottom of a feeling that has gnawed at the edges of my wargaming pleasure for the best part of 30 years. That feeling could be described as unease, or perhaps, disquiet. At a stretch you might even call it guilt.

What on earth does a jaunty kitten-cuddling pragmatist like myself have to feel guilty about? Well, I guess you could start with:

Most of my favourite videogames simulate unspeakably ghastly events.

or

I get pleasure from re-enacting battles that were, for the vast majority of those involved, acutely miserable and disturbing affairs.

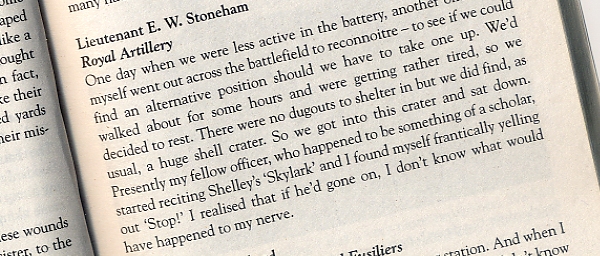

I find it hard to believe I'm the only wargamer that has ever slipped a bookmark into a moving combat memoir or watched the credits roll on a harrowing war documentary, and pondered whether an hour or two of Combat Mission or Close Combat is really an appropriate response to what they've just read or viewed.

And it's not just books and TV documentaries that can trigger uncomfortable introspection. I remember one occasion from a couple of years ago, particularly vividly. I was sitting at my PC engrossed in some WW2 diversion or another, when an unexpectedly loud and deep gun report echoed across the battlefield. It was few seconds before I realised that the sound hadn't actually emanated from my speakers. It had come from outside. Shotgun? Car crash? Terrorist bomb? My brain scurried through all the possibilities until it slammed full-tilt into the explanation. It was the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

Down at my local war memorial a cannon had been fired to mark the beginning of the Two Minute Silence. Embarrassed, I pressed pause.

If I thought there was an easy conscience-salving answer to the question: "Is it unseemly to use real suffering - real sacrifice - as the basis for breezy entertainment?" I wouldn't be writing this piece. Then again, if I felt that the genre was irredeemably sullied, I wouldn't be contemplating a contented afternoon with Combat Mission: Battle For Normandy. Like all thoughtful, practising grogs, I've mused on the question and found enough moral wriggle-room to justify continued pursuance of the pastime that I love.

If I ever found myself having to defend the morality of wargaming, I'd probably drag out the genetic argument at some point. I'd claim I was just doing what men have been doing for thousands of years: sitting in my cave/hut analysing old battles - old hunts. I'm hard-wired to wargame. Hard-wired to find tactical situations endlessly fascinating.

I'd probably also try to gloss over the wargame industry's frequent failure to acknowledge the dreadful emotional and physical consequences of war, by pointing-out that most grogs are well read, inquisitive people that gain such insights elsewhere. I'd hope my interlocutor didn't press too assiduously the point that ignoring war's least wholesome sights and sounds (while often obsessively modelling such tactical irrelevancies as flowers and birdsong) leads to representations of war that are grotesque in their lack of grotesqueness.

We wargamers might be able to accept that our ludological heaven was some poor bastard's living hell, but when it comes to setting, we often draw complicated lines in the sand. For some, modern conflicts like Afghanistan and Iraq are too fresh or ideologically charged. For others, WWI is too merciless, Vietnam too resonant. To claim, as I've seen done, that wargames exist in some sort of amoral bubble by dint of their tactical or strategic focus, is to ignore the evidence of myriad forum threads.

I confess my own qualms have rather selfish personal slants and rather illogical temporal ones. Knowing that my great-grandfather fell at Passchendaele means I couldn't throw myself into a wargame version of that battle with much enthusiasm. Not knowing whether my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-etc-grandfather fought at the Battle of Hastings means I can choreograph that scrap with a spring in my step and a song in my heart. I know others that are drawn to a particular theatre or battle precisely because a relative served there. As I said, the lines in the sand are complicated.

Will I ever play a wargame that doesn't make me feel like I'm picnicking on a war grave? I sincerely hope so, but looking around at the recent crop of groggy entertainments it's hard to imagine what that title will look like or who will fashion it. To have genuine power it would need to do a lot more than proffer the fig-leaf load screen aphorisms or cutscene Band of Brothers homages that pass for counterweights in other militarised genres. It would need to make me care more about men than materiel. Feel utterly wretched about casualties. Occasionally it would force me to put my reputation as a CO on the line and question my orders. At times it would probably need to be No Fun Whatsoever.

And there's the rub. All the Battlefronts and Matrix Games out there are trying to ensure I have a bally-good time, and I'm sitting here troubled by their success. Madness? I'd be genuinely fascinated to hear what you think.

Do you reckon the makers of wargames have any responsibility to the warriors they depict beyond ensuring uniforms, muzzle velocities and armour thicknesses are correct? Is there something morally dubious about finding relaxation and pleasure in simulations of situations in which relaxation and pleasure were impossible? Did the poor buggers whose names are engraved on our war memorials die so that we could re-enact the battles in which they perished over and over again?

Maybe I'll give it some thought as I play CM:BfN this afternoon.

Then again, maybe not.