Wot I Think: Castles In The Sky

A Bedtime Story

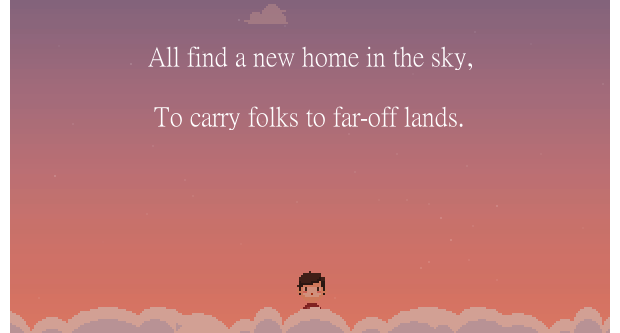

Castles In The Sky, the debut game from indie studio The Tall Trees, doesn’t look like much. Its little pixellated window is like a peek into a giftbox you might find in an Edinburgh gift shop. A miniature boy is holding a little balloon as if framed on the wall of a childhood bedroom. The premise of this game is small too. In Jack’s email to me he’d tell me ‘It's a videogame picture-book about a little boy who decides to leave the earth far below, and goes off exploring in the wide blue sky’. A picture book, I thought. I expected a pleasant story. I expected not much in the way of the trappings of videogame canon: that world we come from where a health bar happens, or where a collectible might demand our attention. Sullenly, I ran the game, and expected to like it, but not think anything further of it. But sitting down in an armchair just after dinner, I experienced the unlikely: what it is like to be proven wrong.

As I’m writing this, my little cottage in Brighton is quiet. The low swishing hum of the dishwasher ruminates over the scrubbed surfaces of our little kitchen, behind me the radiator has just gurgled a little into life and is somehow gently heating my chair. My belly is full in a way it hasn’t been for a long time. I am sitting here regretting being short with a game designer who wanted me to play his game because it mattered to him. I am sitting here feeling a sense of being humbled.

I was short with the lovely designer of Castles In The Sky because my laptop refused to run it at first, and I was travelling, and I had very little money and all the burdens of life had collapsed on me. That week I’d regretted choosing to become a full time writer, I’d regretted choosing to be an advocate for a medium that I sometimes feel doesn’t really want me or can’t sustain me. I’d started to become that thing that no one wants to become: a critic who stopped understanding why she’d ever started to write about something in the first place. Someone who had recently been writing because she wanted to make fun of things, not because she loved things. Being on this path is like playing Desert Bus: you must constantly correct the drift on your steering. Sometimes editors correct my drift, sometimes I have to do it for myself, but this time - this time, it was the game that corrected me.

On a Sunday afternoon, with the rain lashing down outside and all the silence in my house inside, I felt a particular sense of freedom radiate from the little boy sprite, with his hair waving in the wind, grasping his red balloon and heading up and up into the sky. In part, this feeling comes from the gently undulating soundtrack, a sort of opiate-sweet coma that makes the clouds seem more marshmallow-like in texture. Headphones are mandatory for this game; the reverent womb the music makes of your chosen device is like that feeling you get when you run hot water into bathwater gone cold. Your toes wriggle in lethargic joy. Or the feeling you get when you’ve just walked into your house from a thick, buffeting storm outside, and the fireplace is lit inside, and someone you love has already put the kettle on.

And yet the sense of feeling free, or let loose to fly, comes from a familiar mechanic. The idea is to jump the tiny blushing sprite up and up into the blue sky as night falls; to do this you hold down the mouse button to charge up a jump, and then release to ping joyfully into the sky. When you let go a grin spreads widely across his face, reflecting how you should feel at the release of the jump. The little boy will hang there idly in mid air before he begins to drop slowly onto a cloud of your cursor’s choice, and you climb more from there. If this were a platformer, perhaps this would be boring. But this isn’t really a platformer, so much as a bedtime story. This is more like taking a journey back into your childhood, where when you looked up at the sky, you thought clouds might be able to sustain your weight, if you wanted. When clouds were reachable platforms for all your idle thoughts.

The little ping-to-fly sensation is one I’m familiar with: it has the elastic of Joe Danger’s jump-feel with a slow languid pace. The hold-down let-go is one of the most enjoyable game feelings we have, and the drift and land is just right. It has a nice dreamlike quality. And so do the words that accompany you.

As the boy jumps up and up and up, text appears line by line to tell a bedtime story in poetic rhythm, uses your climb to imprint phrases upon the blue backdrop of how you should ‘bend your knees and away you go, to find castles in the sky’. The rhythm is soporific, easy-reading. I imagined myself reading this to someone I loved as I climbed clouds. I imagined that I was reading it to someone who loved me.

Imminently you’ll catch the string of a red balloon again and find that the music drops for some birds to drift by. A little pot plant appears on a cloud and somehow it isn’t out of place at all. You continue on up, the wind always blowing the fronds of your little boy’s brown mop. The sky changes its lazy haze; the shadows move.

There are little orbs suspended in the air that you can collect as you climb; these are not really collectibles. I have come to resent the canonic language that has me call them that; in fact, that I have already used the word ‘platformer’ and ‘collectibles’ with regard to this game makes me feel restrained, like I’ve been handcuffed as a writer. The terms place an expectation on this game that is absolutely irrelevant. You can ‘collect’ these orbs, but they are for nothing but making tuneful noise. They aren’t really for possession; there is no counter. As you ‘collect’ them, they ping little toy bell notes that are their own reward - there are no other sound effects in the game. Those noises remind you of play like it used to be when we were very very young, when play wasn’t a competition but an experience, a journey you were on to make your environment tell you something. When you made mud pies just because you could. That’s why we’re here, isn’t it? To play? Play is its own reward. The orbs are their own reward. They are not ‘collectibles’. You cannot use them to redeem a prize, like tokens at a village fair.

The music changed. I travelled above a wall of cloud into a blushing dusk, and the words suggested that all lost balloons, wherever they are, would find new owners.

There’s a rush of old feelings for me in that moment where those words clash with a hot air balloon rising proudly from behind the cloud cover. My heart swells. I don’t recall primary school; I’m not quite sure what happened but I have blocked out the memory of that time. But the game’s idea that all lost balloons might find new owners is an allegory that hauled up the hopes that I think my ten year old self had once. I think perhaps ten year old me wanted to think that all lost balloons are found by someone, just like all little boys grow up, except one.

At some point in the night, fireflies appear.

The best games, the ones that make your limbs ache, the ones that make your eyes water, the ones that touch inside your mind and reset your faculties like a tiny tripswitch awaking some decadently manufactured android: the best games change something in you by the end. These days this happens more and more often to me than I ever imagined it would. When I was twelve I thought that Tomb Raider was the height of adventure: the only thing that in my teens could possibly have stung me like a cattle prod into leaving Britain’s rain-battered salt-clouded shores, sent me careening through years of bitter-tangy spirits in novelty shot glasses, pockets full of jangling Baht when I needed dollars, and sitting soggy in a jungle whilst grass bugs sacrificed themselves to my dinner.

But recent games have gently curbed my rigid, adolescent idea of what games are. It might seem like games are getting more tiresome, particularly to those of us who have had a lifetime of looking at the stupid art on the front of graphics card boxes. Mainstream games are staying the same, because they continue to want a mainstream audience. But some people are making other games with different ideas in mind because they would like to say something interesting with their mechanics, their story - sometimes both together. Money might still factor. But at least those designers get to hold out their hands to cradle the player. I felt like something had changed in me, by the end of this game. I felt hopeful as my little boy adventurer climbed, finally, into bed.

Castles In The Sky is a tiny window into a delightful bedtime story. I imagine parents reading it aloud to their children as the child is fascinated by the huge bounds the boy makes through clouds. Very little happens but kites and planes go by; the music gently ebbs into your mind and as the story ends you feel peaceful and contented. It has thawed me a little, from a week of thinking only about GTA V and how serious life must be all the time. It has made me think about how five year old me used to listen to stories in our community library crosslegged and have to shut up, at least for a little while.

There’s that bit, isn’t there, in Pixar’s masterpiece Ratatouille, where France’s infamously grumpy and difficult to please critic Anton Ego is cooked a meal so evocative of his mother’s cooking that he cries. I admit to feeling this way about this game. This silly little game thawed me like a discarded Calippo. I beg of you, particularly if you have a young family - and even if you don’t - you should play this tiny game and feel content, at least for a little while. It’s just like eating a really great ratatouille.

The game comes out on October 18th, but you can preorder it here.