RPS Interview: Valve's Erik Wolpaw

Erik Wolpaw is fated to only ever be refered to as "one half of Old Man Murray", rather than "co-writer of Psychonauts and writer of Portal". So today we bring you our interview with one half of Old Man Murray, Erik Wolpaw. We discuss what it's like to work for Valve, how GLaDOS came about, the role of cake in games, and, of course, why all plays suck.

Can you explain the path you took from Old Man Murray to Valve?

While I was working on Old Man Murray, I wrote my first game, Alien vs. Child Predator. It remains one of just a handful of games to mix addictive Pokemon-style creature collecting with North Carolina's sex offender registry. It was self-published and not widely distributed or played or, honestly, even really that enjoyable if you think about it. It did, however, catch the attention of some lawyers who work for Twentieth Century Fox and Tim Schafer, who hired me to help him write Psychonauts. After Psychonauts went on to be very, very popular in Europe, I got busy with my next big project: being unemployed. One day, while I was wondering where I was going to live when I couldn't pay the rent next month, I got email from Gabe Newell asking if I'd like to be a staff writer at Valve, famous creators of Half-Life. I figured Gabe was a fan of Psychonauts, but it turned out he had absolutely no idea what Psychonauts was. I guess he just really, really liked Alien vs. Child Predator. That's honestly pretty much how it happened.

How was working with Tim Schafer? How does such a collaboration work?

Oh man, Tim is great and also everyone else at Double Fine is great, including everyone who was responsible for the f'ing Meat Circus. Did you watch the trailer for Brutal Legend? So, so awesome. When the music kicks in and the lead character makes the metal sign and runs right at those robe guys and then cuts them all in half? I mean, come on. It's gonna be the best game ever until probably Portal 3 or 4.

Anyway, the best thing about working with Tim was that I could completely trust his instincts. If I wrote something, and then Tim thought it wasn't that strong, I didn't have to waste any time agonizing over whether he was wrong because he was right. He's like a big comedy safety net.

Collaboration-wise - and this is discounting the part where I'm snuggled safely in the bosom of Tim's comedy net, which is specifically a Tim Schafer thing - it was a lot like every collaboration I've ever had. You sit in a room with someone, and you expend a lot of energy thinking of ways to postpone doing any work. After a while, you start saying the vilest, most offensive things you can think of in a desperate attempt to crack the other guy up. This sort of greases the wheels for eventually writing a line or two of usable dialog.

So what do you think is the hardest thing about writing for games?

At strip clubs, there's a guy whose job is to talk between the strippers. He tries to do a good job and be entertaining and enthusiastic, but everybody's just there for the nakedness. That's a professional writer trick we call called an "analogy". What I really mean is that game writers are the game equivalent of the guy who talks between the nude girls at strip clubs. Nobody cares about what that guy does, and anybody who does care is probably a little maladjusted. So I'd have to say the hardest part of being a game writer is learning all the writing tricks like "analogy".

When you moved to Valve - that must have been a strange day - what did you expect to be doing?

I figured I'd be spending most of my time getting fired in a few weeks. Thank God for Portal and Team Fortress and Valve's decentralized management structure that created an environment where nobody 100% knew who had the authority to fire me until I was able to actually make a meaningful contribution.

The promo movies for TF2. Whose idea were they, how did they come about?

Honestly, I'm not sure whose idea it was. Oh no wait, I remember now: MINE. I'm kidding. Valve talks a lot about "collective design process this" and "collective design process that" to the point where, if I were me before I worked here and stopped swearing so much, I'd be like, this is some fake-ass marketing-ass Bigfoot-ass legendary bullshit. But, honest-to-God, I've seen it with my own eyes. Valve is the most collaborative creative environment I've ever heard of much less experienced. So the shorts grew out of basically everyone at Valve's desire to see these awesome TF characters put through their paces outside the constraints of the game. We did the Heavy as a proof of concept, and kind of freaked ourselves out, and then immediately decided to move ahead with the other eight.

Two things stood out to me most when playing Ep 1 and Portal. There was the fluidity of both games, keeping you moving forward while always feeling you were being challenged. And there was the writing. Far more than the series has ever been before, Ep 2 was a narrative experience. And Portal, essentially a puzzle game, was intricately narrative-driven. Why do you think narrative is so important in genres that traditionally leave the story short?

In defense of games, I want to point out that the writing in plays, including everything by August Strindberg and The Lion King, is 100% pure crap. So we're doing better than they are even though they have the benefit of mostly not being about space marines.

That said, most games shortchange the story because, frankly, they can. Don't get me wrong, I love a well-written game. But I'm not gonna kid myself: Good game + crappy writing is probably still gonna more or less equal good game. It's like how the Precious Moments Special Edition Bible is extra good because it has Precious Moments illustrations, but even if you completely subtract the Precious Moments stuff, it's not a whole lot less good, because it's still the Bible.

Tell us about GLaDOS.

We wanted an adversary personality that hadn't been done to death. I mean, GLaDOS does yell a lot and shoot rockets at you, which I guess is fairly traditional, but she's also kind of supportive and funny and sometimes she's a little sad and even scared. You get to know GLaDOS over the course of the game and, hopefully, you feel like your actions are really putting her through the wringer emotionally. We give you some quality time to luxuriate in all the emotional pain you're causing her, which, I think, is a lot more satisfying than simply throwing a bomb into her exhaust port or whatever. That's not to say she doesn't get a few zingers in herself, though. She says some very hurtful things and, honestly, by the end, it's pretty clear that this sick relationship is unhealthy for both of you.

One of the most outstanding features of Portal is the development of that relationship. Could you talk us through her mindset, and the changes she goes through?

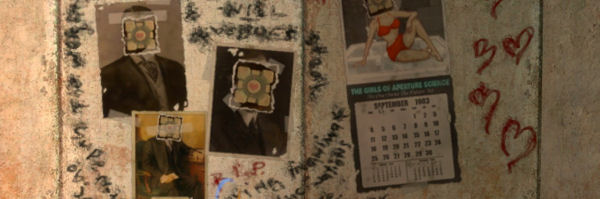

We designed the game to have a very clear beginning, middle, and end, and we wanted GLaDOS to go through a personality shift at each of these points. She starts out as the supportive (though increasingly sinister) institutional voice of Aperture Science. Here, she's mostly delivering exposition about the general Aperture mindset. After you escape, she speaks as herself for the first time. She starts referring to "I" rather than "we". She begins to sound more desperate here, now that she's lost some amount of control, and a lot more emotion creeps into her voice. Finally, in the last room, you destroy the morality core and, as she becomes more unhinged, she switches to an almost human-sounding voice. When we were still fishing around for the turret voice, Ellen did a "sultry" version. It didn't work for the turrets, but we liked it a lot, and so a slightly modified version of that became the model for GLaDOS's final incarnation.

Also, there is cake. Why's that?

Well, there are lots of message games coming out now. Like they've got something really important to get off their chest about the war in Iraq or the player is forced to make some dicey underwater moral choices. Really, just a whole heck of a lot of stuff to think about. With that in mind, at the beginning of the Portal development process, we sat down as a group to decide what philosopher or school of philosophy our game would be based on. That was followed by about fifteen minutes of silence and then someone mentioned that a lot of people like cake.

Then there's the popularity of the Weighted Companion Cube - it's insane. How do you go about creating a plastic box that everyone falls in love with?

That was all our project lead, Kim Swift. It was her idea to put a heart on it. Boom - instantly likeable.

Not enough games have a song at the end. Especially a dark, threatening song set to happy music. How on earth did you convince Valve bosses it would be a good idea?

It's true! Not enough games end with a song. God Hand does, and that's one of the many reasons it's so great. As a game player, it was always my dream to beat a boss monster so f'ing hard that it starts singing. Last year, Kim sent me some Jonathan Coulton mp3s along with a note saying she'd invited him to visit Valve. I don't think anyone knew exactly what he might do. Maybe he'd write a Team Fortress jingle or a ballad about something Gabe said about the PS3 or, really, who knows? We just knew he was awesome and we wanted to talk to him.

Once Kim and I met with him, it quickly became apparent that he had the perfect sensibility to write a song for GLaDOS. We talked to the rest of the team, and they were on board. And then we talked to the people who'd have to actually pay for it, and they were - understandably - slightly more skeptical. It's a testament to them and to the Valve process, though, that they let us give it a shot.

Both Ep 2 and Portal are really very funny. Funny in a way we haven't seen Valve games try since the original Half-Life. What do you think is the larger role of comedy in games?

Did you see the presentation Valve's Jason Mitchell made about the process Valve went through to design the TF characters? Amazing. I wish that part of Valve could work on answering this question, because I don't have a lot of smart theories here. I basically think all games should be funnier. And all movies and books and food. I don't give a crap about plays, so they can continue to be depressing.

Valve's design ethos is focused on constant play-testing throughout development. How has this affected how you work?

As I kind of hinted at in a previous answer, it means we can try stuff like having GLaDOS break into song, and everyone at the company is secure in the knowledge that there's a more or less objective process for determining whether that idea, in practice, sucks. I know for a lot of people the idea of focus testing has a whiff of an anti-creative sort of design-by-committee-ism. But, at least the way it's practiced at Valve, I've found it to be utterly liberating. People are a lot more willing to try risky ideas when implementing and testing risky ideas is a fundamental part of the design process.

With Valve's notoriously long development cycles, and no other games currently announced (beyond the assumption of Episode 3), what are you set to be doing next? What are the duties of the Valve writing staff between games?

Hold on, I never finished answering the earlier question about what's really hard about writing for games. Say you're writing a play; the pressure's totally off because nobody expects it to be anything but 100% pure crap. So writing for games is definitely harder than writing a play. Writing your own name is another thing that's harder than writing a play, though, so that wasn't too great a comparison. Luckily, I was just getting warmed up. If you think reading a book is hard, you should try writing one. Because it's even harder. It's still not as hard as writing a game, though. If you discount the purely visual pop-up parts, a book is made almost entirely of words. As a novelist, you just need to think of a few decent strings of words and then fill the other 98% of the book with more or less random descriptions of things and exclamation points. In a game, the 98% garbage section is filled with the actual game. Even worse for game writers, the 98% garbage part of a game isn't even usually garbage because instead of reading something boring about the history of Belgium, the "reader" probably gets to jump a Camaro over a dinosaur. That means the pressure's on to make the two percent wordy part that you're responsible for really, really spectacular. It's a tough job.