Retro: Fable

Lionhead aren’t good with interfaces. Black & White’s wavy-hieroglyph spellcasting is infamous, of course, and I spent a little too much of the Christmas just gone swearing at the agony of magic selection and food-eating in Fable 2. Revisiting Fable the first though, the sequel comparative;y seems like a masterclass in elegant menu-making. This action-RPG’s wheezing, long-winded inventories, quest logs and maps are what you’d expect a taxman to come up with should he sidestep into game design. What game in its right mind would hide Quit under options? I wonder if it's a failing that started at Bullfrog - Evil Genius and Republic, by that other 'frog splinter cell Elixir, were similarly blighted by awkward menus. They're like a great writer who's never quite mastered apostrophes, and moreover doesn't care. As long as he gets his point across, he's happy.

I wonder too if a great clash of interface design is coming. Right now, we’re in the midst of a silent war between a movement that seeks to further complicate games’ controls – as demonstrated by the slow-growing button count on a 360 or PS3 pad, and Walker’s odd reliance on 5-button mice – and another that aims to strip them back. For the latter, look to the Wii and to the most recent Prince of Persia. Fable sits uncomfortably between the two poles. It’s determined in so many ways to be a simple, accessible action game that keeps relatively clear of the statistical overload of more throughbred RPGs, but perversely it carries the sort of dense menus and elaborate controls more common to the beardiest roleplayers. It’s a game at odds with itself.

Which is a theme that runs all through it. It’s a game that shouts about choice, primarily in the option to become a living legend through kindness or through viciousness, but forbids you from ever straying from its very real paths. No doubt Lionhead’s decision to restrict roaming to key quest hubs linked by narrow, enemy-littered roads is deliberate, rather than the simple cop-out it’s been labelled as: it wants to point you at fun stuff, not endless empty fells.

In truth, it doesn’t matter that much – it’s pretty enough and populous enough to distract from its geographical slightness. It’s how it depicts the restrictions that sours the deal: all flimsy wooden fences and tiny stone walls. In asking to accept that those, of all things, are impenetrable barriers in a world of might and magic, it’s insulting. If a game absolutely must tie its players to a beaten path, there are better ways to do it than visibly breaking its own rules.

Yet for all the backwards design decisions like that, Fable’s Albion – even its land’s name is singularly British – feels far more alive than, say, Fallout 3’s Washington, or World of Warcraft’s Azeroth. That’s not casting aspersions on other developers – Fable’s is a far more exaggerated world. Its people pay no heed to each other. They exist only to react to you, whether it’s to cower in fear of your famed murderousness, to coo in delight at your noble prowess, or to disparagingly shout whichever self-demeaning nickname you’ve currently adopted.

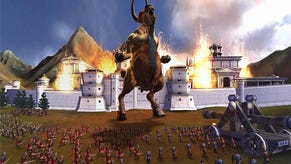

Oddly, this single-mindedness makes the place feel more genuine: their every reaction only to something that actually happened, and your ever-mute character’s total lack of verbal response leaves the other half of the conversation safely in your own imagination. Meantime, guards and traders stomp and totter between the towns’ connecting roads, there to bully or to barter with at your discretion. Thanks to their exaggerated swaggers and cartoonishly bloated limbs, you don’t look for cracks in Fable’s reality – instead, you accept the world it paints. Had Fallout 3 not chased photo-realism, its many animation failings wouldn’t have been anywhere near as glaring. As it is, this remains a remarkably pretty game: like WoW, there’s a certain timelessness to its toy-like character designs.

At the time, Fable was both praised and hated for its moral choices – choices that, as has forever been the case in games that make similar promises, were pigeonholed into a simple Lovely and Horrible dichotomy rather than reflecting any sort of inbetween status. Looking at it now, the morality seems far less important than it did in 2004. It’s a choice we’re so used to now, and the only difference here is that your character visually reflects it: angelic light and butterflies for a goodie, satanic horns and sulphurous insects for a meanie.

The morality, then, is ultimately incidental - charming polish rather than the meat of the game. What Fable really is is a particularly relaxed action game set in a particularly adorable, self-effacing world. With the exception of the awkward spell-selection, combat is simple and visceral – again, the toytown characters and Looney Toons animations do it many favours. It’s a chummier Diablo, happy to let you wander off and get married or beat up a few NPCs for while, but ultimately waiting for you to walk a familiar thump’n’collect road. Occasionally, a sterner voice asserts itself – there are a couple of hard choices, a few moments that pluck at heartstrings – but the ultimate impression is that it’s a playground. Like every playground, though, there’s an unavoidable barrier on every side.