Wot I Think: Thomas Was Alone

Stop doubting Thomas

Thomas Was Alone and he was also a Flash game but now he’s grown up and it’s time for him to meet some new friends and set off on a journey that will change them all forever. It’s a tale of friendship, co-operation, sentience and rivalry, but is it possible to care about a gang of abstract shapes and the puzzling environments they traverse? Here’s wot I think.

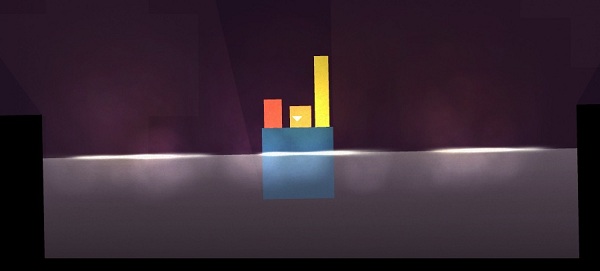

There are heroes, freaks, villains, sages, friends, enthusiasts and lovers in Thomas Was Alone. Every last one of the cast is represented by a quadrilateral shape, of various colours, shapes and sizes, but they have more character than your average bald space marine and many of them even have character development. Their abilities combine with the narrator’s insights into their thoughts and what begins as a minimalist experiment in co-operative (though single player) puzzling, grows into a quest, with conflict as well as companionship.

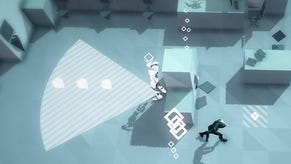

At heart, which the game has a lot of, this is a puzzle game. Levels are obstacles to be overcome through some light thinking and basic platforming. All of that is fine, if a little easy save for a couple of levels that stumped me for a good while, but it’s the look and the sound of the game that make it stand out.

The design is minimalist, with barely anything wasted. Characters are basic shapes because that allows them to form stairs for one another to climb, and makes them feel part of their world of edges and corners. They don’t speak but their conversations and interactions are described by Danny Wallace’s narration, which works well, although it is at its best in the game’s earlier, emptier stages. The music beeps and bops away, its melancholy bursting into an electronic longing during the most difficult challenges.

It’s the characters that make the game linger in memory though, those featureless shapes. Let’s take a look at Chris, the most inept of the lot. He’s a square square, squat and dumpy, with the agility of a damp towel. Because his jumps are so puny, he needs Thomas and the other shapes, he needs them to lift him or to carry him, sometimes a whole group of them banding together to make sure he isn’t left behind. If this were a utilitarian game, Chris is the one you would happily leave behind because he doesn’t have any great secret ability to make up for his lack in every other area.

He’s the bard you took along on a dungeon dive because it seemed like a good idea at the time, but then you realised that a bloody massive axe is a lot more useful than a warsong plucked out of a lute by an elf in a funny hat. Like bards, Chris can also be an obnoxious little blighter.

Moaning, complaining, griping. Those are Chris’ abilities. He’s never happy, always annoyed by the enthusiasm and energy of his new-found allies, and the harder they try to please him, the more disgruntled he becomes. Everything changes though. Just as Thomas isn’t alone for very long, Chris has a story of his own and while he doesn’t exactly become Mr Positive, he finds it in him to enjoy the company of others.

There are ten chapters to the game, each divided into ten levels, and the beginning of each generally introduces a new character, meaning that while you’ll only have to move two blocks through the early levels, later on it’s necessary to navigate through the same area several times. The trickiness comes from ensuring each of the characters makes it to a specific portal, a white outline the same shape and size as them. To do that they often have to rely on each other, whether by having a capable companion scout ahead and push switches to create new passageways, or by trampolining on one another, or using Claire as a boat.

Claire is the only one who can survive when she touches water, floating triumphantly across great stretches of liquid, which leads her to believe she’s a superhero.

As with many puzzle games of this sort, the biggest irritation for me is the point when I figure out how to get every piece into the right place but wish I could just make them be there already. I like the process of figuring out the level a damn sight more than the process of actually completing it and most of Thomas Was Alone is figuring out rather than timing or platforming. Still, the slight annoyance of travelling through levels can be compounded when there are five characters following almost exactly the same path, one after the other. Go right, jump, jump, drop down, go right again, jump, drop, dodge spike, ride moving platform. Done. Switch character, go right, jump, jump…

Fortunately, the majority of the levels are cleverer than that, often separating the shapes and giving them their own sections to negotiate. When you have four or more, they’ll often be in two separate groups so that the collaborative nature of the puzzles isn’t discarded for variety’s sake. Still, there were moments when I let out a sigh that could have powered a small windmill as I realised I’d sent a character right to the end of a level but needed her back at the beginning in order to help tiny little Chris over a tiny little obstacle. But to move her back I’d need Thomas to meet her halfway and help her over a different obstacle and basically everyone was in the wrong place.

It’s good to know then that it’s not just aesthetically that the game shines within the limits it has set for itself. Controls are simple, smooth and accurate. There’s no momentum to carry characters over an edge, just the precision needed for perfect placement, which, on later levels, is extremely important. Play with a new character for a minute or two and you’ll instinctively know whether they can jump over a block just by looking at it. That’s partly due to the clean, sharp visuals but it’s also thanks to each shape feeling just the right weight.

I’m also grateful that there aren’t many levels that require use of the restart button. It’s hard to end up in a situation that is unsolvable and dying, by touching water or spikes, isn’t really dying at all. The character reappears at the beginning of the level, or the last checkpoint in the longer or more intricate constructions.

Concerned that the sniffle-inducing soundtrack might be bludgeoned by Danny Wallace’s contributions, I was prepareed to declare the game should have stuck with its elegant textual contextual messages, but the narration is mostly a successful addition.

I wouldn’t be surprised if some of our American friends were shocked to hear Wheatley in another game so soon, and there is a slight channelling of Merchant’s tone, but Wallace’s role is to commentate rather than to enact. In fact, the voicework is at its weakest when he does embellish it with inflections, particularly for one character later in the game. Most of the time, he’s a calm presence and the script is clever, sprinkled with character-based humour and self-deprecating asides. I don't want to spoil the plot so shall simply say that it is surprisingly expansive. Although I enjoyed it, I appreciated the themes more than the details, and kind of wish the final third had been more personal and less grand.

But those themes are there. There's character-based humour, romance, loss, friendship and sacrifice in a game starring some absract shapes. Thomas Was Alone isn’t another lo-fi indie production in which abstract is an excuse for lack of an artist, not that I’d mind particularly if it was provided it played as well as it does; here, the visuals, audio, level design and storytelling are all working to the same end, and while the shapes may have been chosen because they were simple to draw and animate, Bithell has turned any limitations into strengths. Its platforms aren't demanding and its puzzles won't befuddle you for more than a few hours in total, but it does have the finest party of adventurers I've met for a while.

Thomas Was Alone is out on Saturday, available via Desura and Indiecity.