Further Thoughts On Pillars Of Eternity: Animancy & Faith

Another Column

Now that people have had a weekend to spend with Pillars Of Eternity, it feels a bit more appropriate to offer thoughts on parts of the game that would otherwise have been spoiling revelations or moments within the opening few hours. Not core plot events, or twists that may occur, but just the basics – basics I wanted to leave out of my review because it felt like stealing. Stealing the blank slate experience I had from you, in my effort to describe the game.

So here are a first couple of extended chunks I would have liked to have included when expressing and explaining my enthusiasm. Assume big spoilers for themes of the game.

Animancy

It’s certainly a repeated trope of RPG worlds to have magic, or some variety of magic, feared or condemned. But Pillars takes a more interesting approach. Where we’ve seen games with religious organisations persecute mages, or everyone fearful of those who turn to blood magic, here it’s the merging of magic with science that leads to fear.

Animancy is the rather peculiar combination of the understanding of theological matters like souls, and pragmatic, evidence-based scientific research. With its being widely understood that souls enter bodies at birth, and leave at death, Animancers wish to understand this process better, experiment with it, and perform research. Which of course means meddling with souls – something that’s perhaps more understandably problematic to the religiously inclined. With the phenomenon of the ‘Hollowborn’ – children being born without souls, existing as barely sentient shells – Animancy’s role has come to the forefront once again, perhaps offering the most likely source of a solution.

This theme allows the game to subtly prod at real-world subjects, such as the role genetic science is increasingly playing in fertility medicine, putting forward arguments from those who see the benefit in the advancement of understanding how souls transfer between lives, and arguments from those who believe it “playing god”. Or indeed gods. It asks broad questions such as, “Is a child without a soul still alive?”, allowing the player to interpret the topic as they will, perhaps even raising questions about mental illness and eugenics.

People’s fear of Animancy feels somehow far more recognisable than the more traditional revulsion at magic. Sure, it’s understandable that the ability of a certain group to cast fire out of their hands, or control the minds of others, could cause some amount of concern. But there’s not a direct comparison of this to be made within our existence. Fear of science, however, is all too familiar.

Animancy’s stepping into the territory of “playing god” earns direct correlation with all manner of media-led scares regarding scientific advancement. Science has had a miserable couple of decades in its attempts to usefully communicate with the public, from the disastrous misunderstanding of genetic modification that has led to terrible dents in progress when it comes to better feeding two-thirds of the world, to the monstrous misinformation spread about vaccination that has led to losses in herd immunity and horrible numbers of utterly avoidable deaths. People walk about with images of ears grafted onto the backs of mice, and beliefs that at any moment parents will be selecting their unborn child’s tastes in wine, and no depth of understanding of what progress is being made.

Drywood’s inhabitants know about the disastrous attempts to put animal souls into the body’s of Hollowborn children, but nothing of the calm, methodical research into how it is that souls enter new lives, how they move on, and in one particular case, how they stay attached to a life for the time they do. As you experience Animancy within the game, you see both sides. I think Pillars trips up rather badly, here, as it happens. Animancy is far better argued for by individuals practising it, than it’s visually presented to the player. What could have been far more nuanced is made very clumsy by the presence of a ghastly, medieval dungeon in which the mentally ill are experimented upon by cruel lunatics. There’s a cack-handed attempt to suggest that some denizens of the institute aren’t aware of the experiments going on downstairs, but since any of them could pop down and look at any time (with the exception of one statue, it’s fair to point out), it doesn’t feel realistic that they’re blissfully ignorant in their libraries above.

Since the game asks you to think about the ethics of Animancy, and indeed to make significant decisions regarding it, I do wish the reality of what you see could have better matched the often excellent arguments being made by its practitioners. There are equally excellent arguments being made against, and they don’t rely on the existence of torture chambers. I chose to make my decisions based on the intellectual offering, which made it far more morally intriguing to think through.

Faith

The nature of Drywood’s predicament means many of the conversations you’ll have with people will relate to the causes of the Hollowborn. As the people of Dyrwood worship many different gods, there is a confused mix of theologies backing people’s understanding and interpretation of the events. More nihilistic gods like Magran or Skaen might lead someone to believe it a necessary death of humanity. Worshippers of Berath might find it far more challenging, interrupting as it does the cyclical nature of a soul’s existence. Others more fatalistic believe to it to tie into the death of a god, Eothas, a curse left behind after his destruction. Others still see it as based on the actions of certain people in power. Superstition is rife, and the consequences of such superstition can be horrendous.

Again, multiple gods is nothing new to RPGs, and especially not those based on various D&D licenses. But what’s intriguing here is the blank slate of a new ruleset means you don’t arrive with your previous knowledge of D&D or AD&D understandings of gods. Creators? Ascended beings? You’ve no idea.

It does, as I pointed out in my review, touch on the troubling nature of your character’s peculiar lack of awareness of the world they’ve grown up in. Play as a priest and you’ll be asked to pick from six of the deities to worship before you start, but you’ll still go in ignorant of why people follow different gods, and how they conflict. However, as daft as it is that the individual you’ve rolled might not know, it’s reasonable that you don’t, and exploring the pantheistic system is interesting.

It’s interesting, especially, as it’s not forced down your throat. While the fate of Eothas is significant to the plot from the very beginning, and indeed the possibility that non-deific beings could have killed a god asks enormous questions, their role in the story is extremely well delivered. Atheism doesn’t really play a role, but certainly agnosticism seems a viable approach for citizens of this world, even though they may nominally identify themselves as aligned to one particular god.

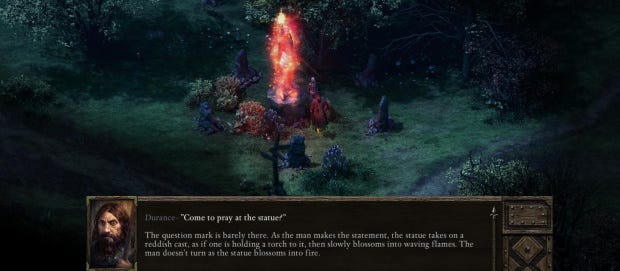

In fact, only one possible party member is specifically zealous in their faith, another finding themselves in crisis at the collapse of their own. Faith is always important in Pillars, but in a way that feels more organic than the manner in which such matters are usually delivered. Rather than two people standing in the street shouting about whose god is better, people believe in each other’s, but follow the philosophy of their own. There is little exclusion of others based on this preference presented to you as you play, despite allusions to wars having been fought over such things at various points. Such an ontology makes for a much more subtle game.

Give it a month or so, when people can be expected to have finished the game, and we can have a whole other discussion about this topic.

I’ve other chopped chunks I want to write about, but this piece is already long enough, so we’ll save them for another day. But hopefully this gives a sense of the deeper nature of Pillars that I didn’t feel able to usefully convey in the original review, but rather opted for saying, “Look, it’s just there, okay.” There’s enough lore and history provided or suggested to create a universe that feels far bigger than the story you experience in the 50-60 hours of the game. Hopefully it will be successful enough that one day we’ll get to hear a lot more of it.