Wot I Think: Outward

Pack your bags

Outward is the first game I’ve played to capture a feeling I remember from childhood. Waking up so early it's still dark outside, and being wide-eyed with wanderlust. I’ve always loved the hour before dawn, simultaneously blessed with twilight tranquility and electric with promise. It feels like stealing something from the sun, enacting some celestial heist to gain a foothold on the day. In this survival RPG, it’s the perfect time to start a journey.

There, I managed the whole intro without mentioning Dark Souls. But yes, Outward is somewhat reminiscent of the popular action RPG, but a survival version of that game. There are fights with wolves and beasts, but mostly this is about the difficulty of travel, not combat. Daylight itself is a resource, vital but limited. When night falls, darkness is heavy and impenetrable. A real hindrance, not just a filter gesturing at the absence of light. Players hoping to see further than three feet in any direction will need a lantern when night falls. But money is tight at the start of your journey and a backpack big enough to hang a lantern on is expensive.

So, I start my journey an hour before dawn, to stretch out the daylight hours. I’ve been promised payment if I venture to a nearby cave to retrieve a rare mushroom for a villager in a settlement nearby. Outside the village gates are open fields, and I notice the shadows of trees shifting with the sunrise. Red berries decorate nearby bushes. In the distance are mountain slopes encircled by an enormous, ornate bridge. I’ll come to rely on that mountain, central and tall enough that it’s visible across the world, because there are no quest markers in the game, or even a marker on your map to show where you are.

What initially feels like having a crutch kicked out from under me, I soon learn to appreciate. Faced with a confident, unwavering design choice, you can only really respond in kind. I’ve got a map, and a compass. There are roads, and signs, and landmarks. I’ve listened to dialogue, and I have a journal. A longing to borrow Geralt’s GPS soon fades, and again, each of these footsteps starts to feel more like my own for the lack of guidance.

I’ve pared down possessions to the essentials. A skin filled with fresh water. Travel rations cooked from fish I caught at a nearby beach and preserved with salt I’ve collected from boiling sea water (cooking and crafting is done with a click ‘n’ drag menu). I have a hatchet I found lodged in the bark of one of the trees that grows in the village. A battered wooden shield. Bandages. There’s room in my bag for more, but I need space for animal skins, spare weapons, rare plants. Anything I can sell to repay the debt I owe the village. They have given me five days to pay before I lose the lighthouse I call home.

The way Outward’s world is designed has me thinking about the difference between “space” and “distance”. Your custom-made character needs food and water and sleep, they need to be mindful of temperature and diseases from uncooked meat or unpurified river water. But none of these needs are so pressing that they become the central focus of your story. You can catch a common cold, some diseases make you do less damage in a fight, for example. Or you can die in the snow because you aren’t wearing the right clothes, but there’s nearly always a tree close by to harvest enough wood for a simple campfire to kneel by for warmth. These survival aspects serve a purpose, though. They turn “space”, a big tract you simply need to cross, into “distance”, a landscape to be traveled, miles of forests and deserts; ecosystems. The flu, hunger and climate lends significance to the rote, mechanical act of traversal.

I don’t want to make it sound like it’s all shire-like bucolic bliss though, because you need to kill things eventually. Melee combat is stamina-based, deliberate, weighty, and far more desperate and methodical than it is enjoyable. For a long time, the only weapons you can afford seem to barely scratch all but the weakest enemies, who hit hard in return, and often burden you with debilitating status afflictions. You’re given traps and potions, and later magic, like fire spells. But everything comes at a cost. Each early encounter you overcome feels momentous, but it's relief, not elation, that you’ll come to expect after victory.

There’s no death, only setbacks. If you lose all your health in Outward, you pass out and wake up elsewhere, after a loading screen tells you what happened. I’ve been mauled by hyenas and woken up diseased in a cave. I’ve been pecked by giant chickens until I blacked out, only to regain consciousness dazed by a campfire on a mountaintop, next to a note from the mysterious benefactor who saved my life. I’ve been knocked out by bandits and came to in a mining camp cell, dressed in rags, from which I escaped by selling mining picks to a merchant prisoner until I’d raised enough silver to bribe the guard, who seemed totally unfazed by the all the missing picks.

Two sensations common to travelling are the self-sufficient elation of carrying everything you own, and the gut-plummeting dread when you can’t find your backpack, even for a few seconds. Outward has both of these. Throwing your bag from your shoulders makes you more agile in a fight, but if combat goes south, scrabbling to retrieve it again while deflecting blows is pained and frantic. A compass marker points in the direction of your bag, but I’ve twice lost hours of progress towards getting a decent inventory together after being captured and not being able to track it down again.

It’s here the game’s freedom starts to slip into a seeming ambivalence as to whether you make any progress. There’s an early choice to make that leads to one of three different questlines, each with a corresponding area, so there are paths to follow, but a few mistakes can see you running up against brick walls. There are no experience levels, only trainers who sell you abilities and the occasional stat upgrade for ridiculous sums of money. So if you lose everything ten hours in, hard luck, bud. You’re back where you started, only with less quests to take, fewer items to find to recoup your losses. Did I mention you only get one contiguous autosave per character? Because that is a thing this game does. You can’t just hit the load menu after a big loss. You live with it.

It’s glorious, in a way. Absolutely daring and unflinching in its harshness. Quiet moments crossing forests are zen-like in their tranquility, disturbed by combat fraught with tension from the heavy penalties it threatens. To prepare properly for journeys, I found I had to live in the world, venturing out to gather skins and plants to sell and prepare. Sleeping at night before repeating the process two or three times just to scrape together enough silver for a few healing items.

It’s a process that becomes engaging once you stop expecting the same things from Outward that you normally might expect from an action RPG. It’s absolutely not enjoyable to get zapped to death by giant electric shrimps and have to repeat the fifteen minute walk over again. Especially if you’ve used a bag of buffs trying to take the thing down and now need to go ask some starving hyenas if they’d please keep still while you shave them for potion money. But it is rewarding to learn from these mistakes, to map out the world around you, and learn how to navigate it safely.

I’ve been aiming for a holistic take on how Outward feels, so far. Here is a short break from that to list some things which are bollocks. You can put custom markers on your map, but can’t leave notes. That’s a bit bollocks. Enemies don’t seem beholden to the same stamina restrictions you are. Bollocks. The words you read in dialogue boxes and the recorded, spoken dialogue that goes with them differ wildly. This is perhaps a wry meta-comment on the unreliability of historical record, but is more likely just some additional bollocks.

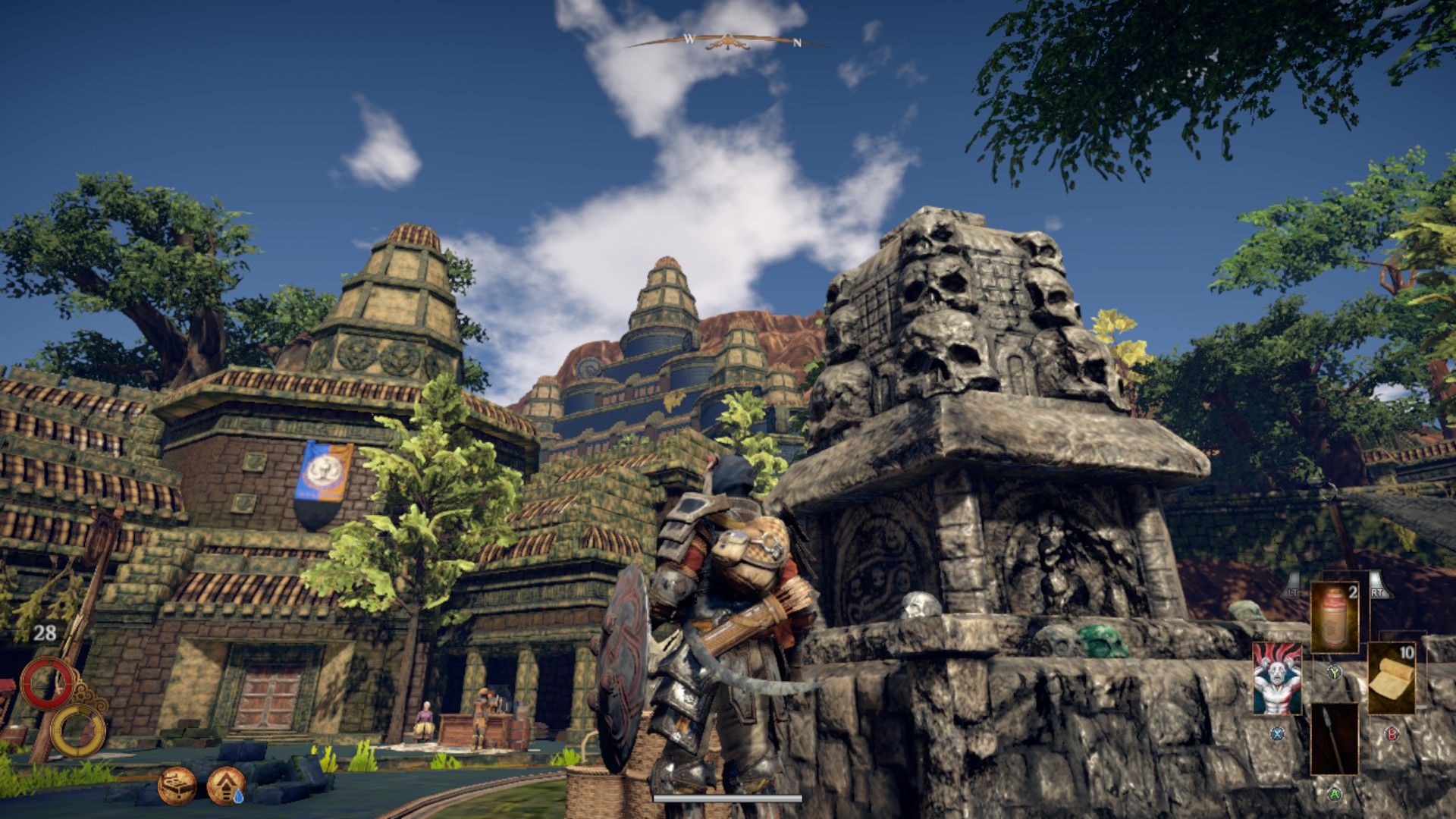

It’s also modest to the point I’m a little surprised it's getting a boxed console release. There’s an architectural and natural beauty to the world when taken as a whole, but there’s also a lot that hints at the idea of castles or bandit camps while remaining sparse on detail. Buildings, equipment and creature design all feel pulled from different places and blended together in a fantasy-flavoured mush. There’s a pervasive, idiosyncratic eurojank to the whole thing, though I don’t doubt that a fair few people are going to fall in love with it for this very reason. Oblivion fans. Two Worlds fans. Risen fans. Go for it.

I am not incredibly enthused to fight more baddies in Outward. I’m not that excited to speak to more of its cardboardy NPCs. I’m not looking forward to getting up from my chair to do some light cardio while I wait for my character to warm up by a campfire in the middle of a snowstorm, so I don’t get diseased and have to trek to the nearest village for a herbal tea and sleep for a day before I’m healthy again.

But that travel, maaaaan. It absolutely nails it. If you’ve ever sold nearly everything you own and bought a plane ticket to somewhere that sounds cool, if you’ve ever read ‘On the Road’ and ‘The Beach’ on an airport bench because you’re that much of a walking cliché, it’ll resonate with you immediately. It understands that a heavy bag can make you feel lighter, for all the cut tethers it signifies.