A Highland Song review: a beautiful snapshot of wild places that stumbles a little

A trip worth taking

A while back, I had a feeling we'd see a lot of games about nature and plants and the wild coming out over the next few years, as developers and players alike emerged from being shut inside for basically a year like dairy cows during their annual spring turnout. We may not all be not be naturally disposed to it, but there's much to be said for the fleeting, if unbridled happiness that comes from running barefoot into the teeth of the wind or getting caught in a rainstorm without a coat.

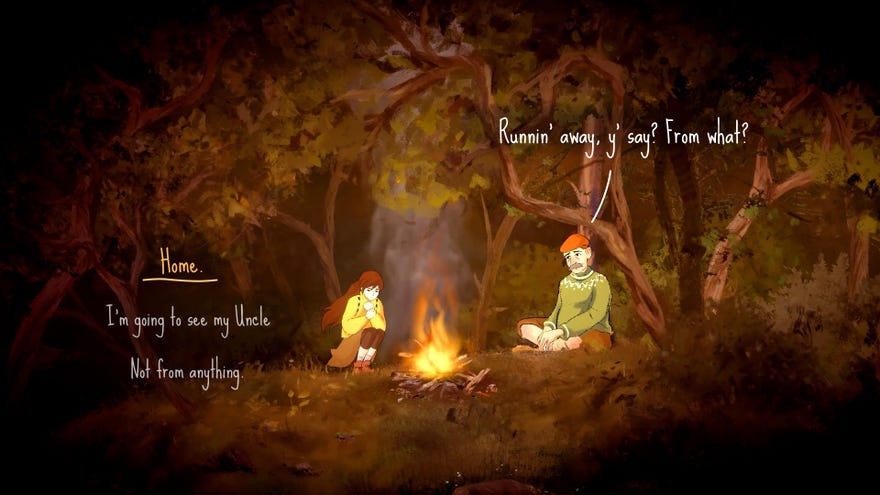

Nine times out of ten, you might get wet and have cold fingers, but that one time that you get wet, have cold fingers and feel red-raw and alive is a doozy. A Highland Song, a lone and dangerous jaunt through the Scottish highlands, is trying to capture that feeling, most especially in segments where you sprint across rocks and heather alongside a deer. At these times you leap in time to swelling music, and whoop and yell in spontaneous joy. It's lovely. It's also easy to stumble.

Partly this is because you will fall somehwere on the sliding scale of dextrous spider trained by the Russian ballet to clumping ham-fingered fool. I, being around the middle, would sometimes get mixed up as to which button I should press on the glowing rhythm-action spotlights that appear when you go for a run. But sometimes my previous leap would send me sailing over the next spotlight, which still counts as a miss, and sometimes this would happen a couple of times in a row. This is a little bit of a theme; it's beautiful and then you run into a wall. Or off a cliff.

But, then again, hiking on your own up and down the highland peaks is a dangerous job. The sprint sections are only a small part of the journey you go on as Moira, a girl who lives on the edge of the hills with her homebody mother. You feel the call to adventure (or, to be more specific, to reach the sea, and your Uncle Hamish's lighthouse by the neap tide at Beltane) and thus set off at a run and a jump with nothing but your raincoat and a backpack. There are only a few days until Beltane, and the process of getting there feels like peeling back the layered 2D mountains between Moira and the lighthouse. You climb a peak, at which point the camera zooms out to show how tiny Moira is, and to let you use a map and try to identify a likely route forwards, a layer closer to the lighthouse.

Inkle, as a studio, seem more at home telling their stories with words than with movement, and the movement is probably the weakest part of A Highland Song, joyful whooping aside. Sometimes you press jump to make a little hop and Moira self-yeets into a chasm or off the top of a ruin like a lemming hurled by a Disney producer. Sometimes she gets stuck on a climb up or climb down for unclear reasons. This collides with the level design, where you can decide whether you're going down the slope in the foreground or up the slope in the background via pressing up or down, but occasionally this will just not work and you have to reverse and run back repeatedly like a sad roomba until the pathing hooks the bit you want.

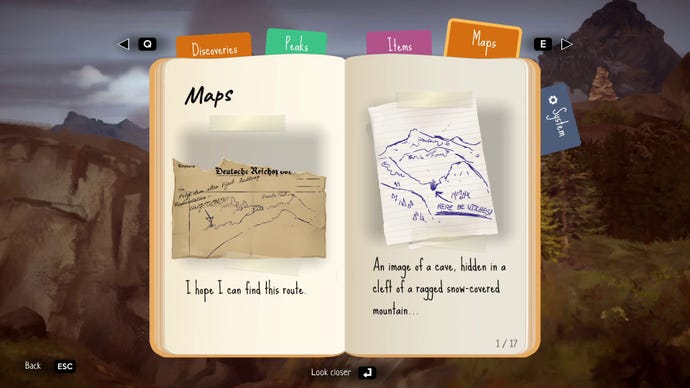

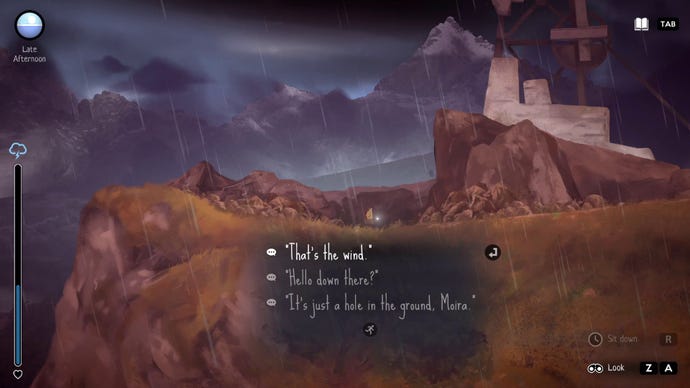

You also only get maps of the route forward sometimes, and they're often hand drawn or fragments that might be hard to match on the peaks themselves. If you reach a peak when it's dark, or if it's cloudy and raining, it's much harder to spot landmarks, adding to the sense of doom. If Moira falls too far (which, due to the self-yeeting, she will) she loses some maximum health/stamina, which also happens if you can't find a bothy to sleep in, and so longer climbs are harder. There's usually more than one route off a mountain, but there are definitely dead ends or optimum ways to climb around a peak. There are also some paths that you're meant to stumble on naturally as part of climbing down a mountain, except if you don't go that way or you run past too fast, then Moira seems destined to freeze on this mountain like a small and less murderous Jack Torrance. To scramble down a big snowy section, half-freezing, only to find yourself staring at an unclimbable gravel slope, is to flirt with selling your soul to Satan. Let it end. Let me not run back and forth on this same section of level for another afternoon of game time.

You won't reach the sea by Beltane on your first attempt. This is frustating, as I have outlined, and it may be so frustrating that some people never try again. The whole of A Highland Song is trying to maintain the tension between progress and difficulty. Climbing mountains is hard for a teenager! Sometimes it works well - for example, only being able to see the full glory of the mountains when you're standing on top of one is fabulous, and worth the sacrifice of having to move on instinct the rest of the time. But there are times that, as it rains for approximately 24 hours, and Moira is unable to effectively rest to regain stamina, and you must inch forwards and fall, and fall again, and go the long way round, that it seems like actual punishment. On my first playthrough, and having identified that if you lost all stamina Moira would 'die' and respawn somewhere useful on the map, I became that Disney producer and deliberatly threw her tiny matchstick body off the highest cliff I could find. This felt contrary to the spirit of the game. Bit of a mental skinned knee.

On your second and third playthroughs, things get a bit easier. You get to keep some of the items you've found (a stone, a boat made of reeds, a bronze dagger, keys that might open mysterious buildings), and your maps. Though there's some randomisation in the little trinkets you can find, and where you find map fragments, the peaks themselves never change. Becoming familiar with them makes it easier, and you attack the journey with more vigour, noticing the way a particular climb has a run of pointing rocks to hop between, a special little joy. You can also linger a little on the marvelous Inkle-y details in A Highland Song. I went to sleep near a standing stone and was visited in the night by a mysterious spirit that protected me. I fed a crow and then followed it to a hidden key. A lion statue demanded to be fed... what? I didn't find it, among my pack of pinecones and old playing cards. One night, by a huge dam, I met a ghost still waiting for his lover. Moira's Uncle Hamish says that the hills are 'awash' with stories, and, indeed, they are.

There is, as you would expect from Inkle, a story within the story to A Highland Song. It's worth exploring further than you dare, to skim those stones and find the birds watching you, to better understand Moira and the wild part of her which will only fully reveal itself if you make your Beltane deadline. But really, A Highland Song is about the wildness we all feel sometimes, and where we go to find it, because the wild places and wild ways are disappearing. As a game trying to take a snapshot of that, A Highland Song is beautiful and does it very well. As a game trying to let us run into that wildness, it trips up sometimes. After playing it, I am left with a desire to visit it again, but also a lingering, vague sadness. I can only be grateful for A Highland Song making me feel that.

This review is based on a review copy of the game provided by developers Inkle.

Disclosure: Natalie Clayton, level designer on A Highland Song, used to write for RPS in the before times.