A Panel Shaped Screen: Rediscovering Moebius, the artist who influenced Sable (and a million other games)

Per aspera ad astra

Talking about a game’s influences is always a tricky business. Sure, developers love to give long talks about the artists they admire. About their inspirations, the concepts they remixed, the idols they wish to surpass. But there’s a difference between the influences they are trying to evoke consciously, and the many-finned chimeras swimming just under the surface of consciousness.

Take Sable, for example. When the game first got announced, everyone called it “the game that looks like a Moebius comic”. It’s easy to see why.

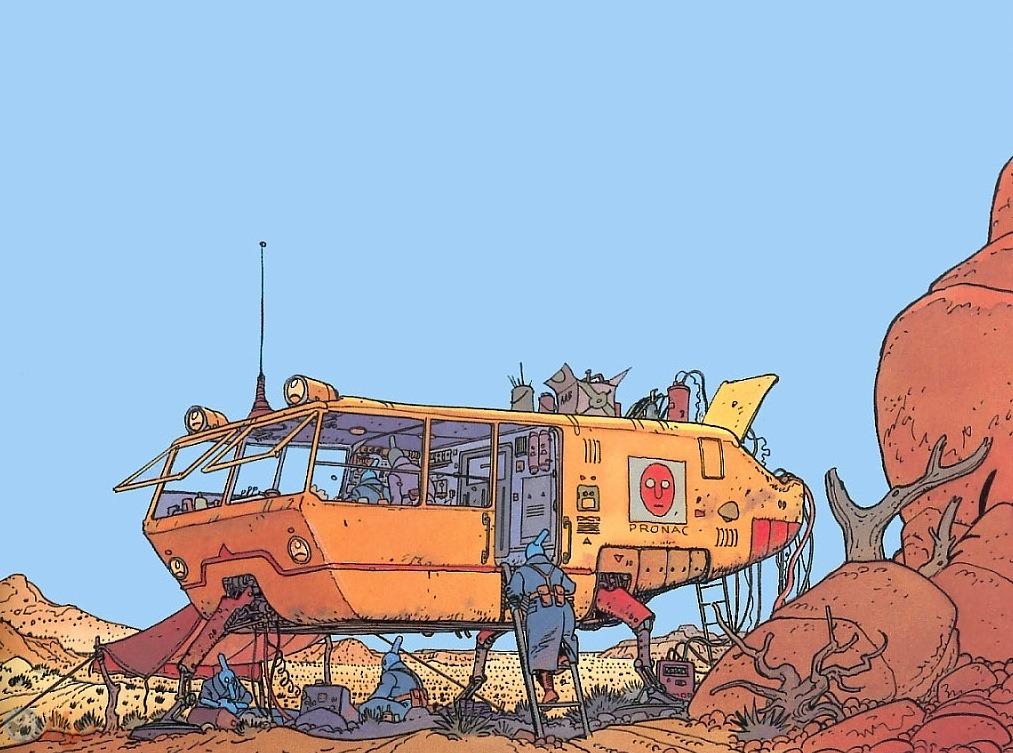

Compare the above screenshot with this panel:

Clean lines. Warm colours. The lonely, quiet desert. There’s a clear similarity between this game and the work of French artist Jean Giraud, aka Moebius. Conscious influences are easy to spot. Celebration through imitation -- and not in a negative way! This is not plagiarism. This is tearing your idols apart and using their remains to build something new.

Some games wear their influences unabashedly on their sleeves. But in this interconnected, globalised world, the web of influences can quickly become too tangled to map -- especially when talking about an artist as prolific as Moebius. The man worked on everything. It's difficult to think of another comics artist who influenced modern pop culture in such a pervasive manner.

Do you think I’m exaggerating? Pick a random game, and I am sure you could find a connection to him. A Six Degrees Of Jean Giraud, if you will.

Halo? Moebius drew a short story for the graphic novel. Ni No Kuni? The first game's animated sequences were done by Studio Ghibli, founded by Hayao Miyazaki, who was good friends with Moebius. No Man’s Sky? The art director cited Moebius as one of his inspirations, of course. The Alien(s) games? The iconic monster may have been drawn by H. R. Giger, but Moebius worked on the design of the human astronauts.

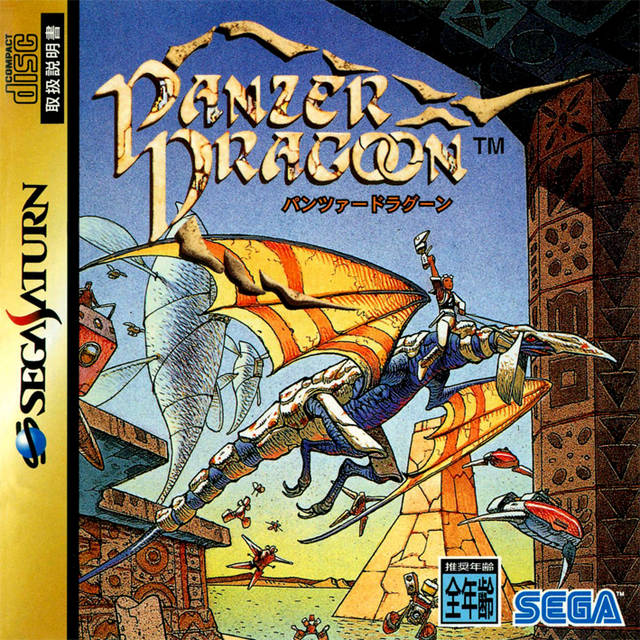

I'm not finished. Let's do Cyberpunk 2077. So, you know the guy who popularised cyberpunk, William Gibson? He has been heavily influenced by Moebius’ proto-cyberpunk comic The Long Tomorrow. An equally impressed Ridley Scott even asked Moebius to work on Blade Runner, but the artist was too busy working on videogame-inspired movie The Last Starfighter. Panzer Dragoon? The first game was inspired by a Moebius comic. He even painted the game’s Japanese cover:

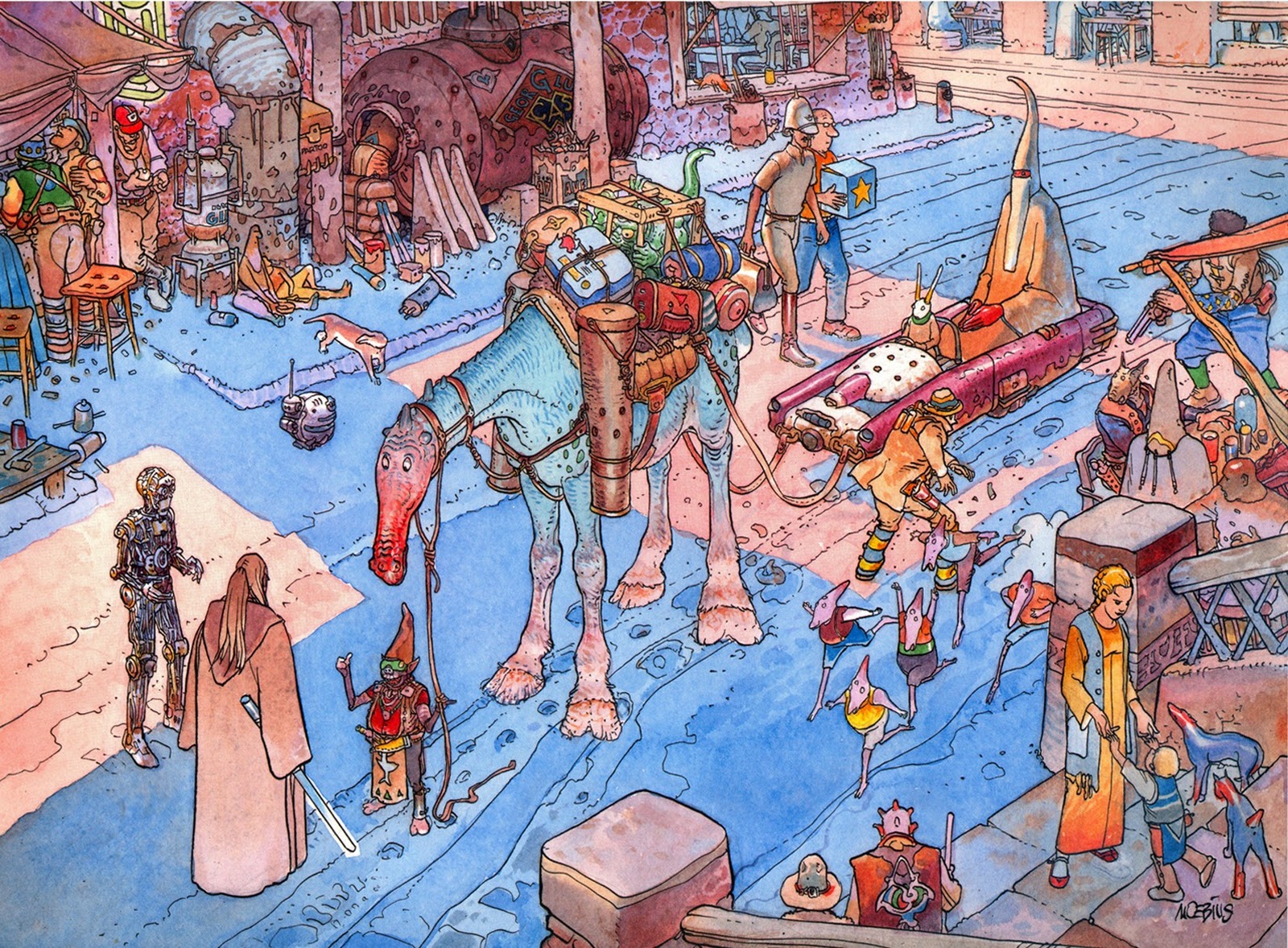

Jean Giraud worked on so many comics and movies he used pen names to keep different careers separated. He used the name Gir for Blueberry, a hyper-realistic Western series. The name Moebius he reserved for his science fiction comics drawn in “ligne claire”, the typical style of the Franco-Belgian school of comics. It’s the same style also used by We All End Up Alone, a promising game still in development about battling cancer and fighting nightmares: uniform lines, no cross-hatching or shadows, and simple characters imposed over ultra-detailed backgrounds.

Over the years, Jean Giraud worked with stellar writers like Stan Lee (on Silver Surfer: Parable) and Alejandro Jodorowsky (on The Incal). But some of his most fascinating comics, I think, are the ones he did alone. Stories like The World of Edena, the dreamy odyssey of two shipwrecked astronauts who have to relearn how to live without technology. Compare and contrast Edena with a screen from Aquamarine:

Like Edena, Aquamarine tells the story of a shipwrecked astronaut trying to survive in an alien world. The premise is similar to Subnautica -- but whereas Subnautica treats fish as enemies or resources, Aquamarine keeps the player detached from the world, enclosed in a transparent bubble. Alien creatures can only be admired from a distance, and are best left alone.

Edena is one of Moebius’s longest solo works, and one of the most coherent. His collections of short stories, like Arzach and The Airtight Garage, are groups of lush panoramas barely connected by a plot. Moebius loved to work in a state of stream of consciousness, improvising his comics without bothering to plan in advance. Storytelling, for him, was just a vehicle to bring his readers to a new world to explore.

Moebius painted walking simulators in comics format. His attitude was the same I now sense in titles like The Herbalist or Journalière: games uninterested in giving you too many objectives, where interactivity is used as a tool to connect a player to a virtual space. Games about loneliness, isolation, and vast emptiness, full of secrets hidden between sparse dunes. Games that make you wander. Games that make you wonder.

I don’t know how many game developers actually read Moebius’s comics. But I like to think (I hope) they have read other comics, or watched movies, or played other games, and some of those experiences were crafted by people who encountered Moebius on their path.

As he grew older, Moebius worked to crystallise his art style, reducing the number of lines, simplifying volumes, and always looking for a purer way to represent the world. He grew increasingly fascinated with the divine, the spiritual and the occult, and talked freely about his experiences with psychedelic drugs. He built stories like matryoshka dolls, with characters changing shapes and running from dream to dream.

I think it’s so fitting, for an artist so interested in the spiritual matter that connects us all, to have become the invisible web that ties so many creators together.