A Panel Shaped Screen: screen shaped panels and games that play like comics

Boxes within boxes

Drawing a comic book is like playing Tetris with narrative beats. You have to somehow put on a page everything the script requires you to draw, give the right amount of space to important moments, make sure the reader’s gaze flows naturally from panel to panel, and all your panels must look nice and clear but also in harmony with each other.

So you, the artist, sketch little layouts first. You shuffle and rearrange the panels, trying to find the right combination before drawing the page. It’s a difficult process, but it can give you the same satisfaction of playing a puzzle game -- so it’s no surprise to see developers turning this process into a literal game.

In Framed, you follow the story of a series of spies dealing with a mysterious suitcase. Each level is a virtual comic book page, with panels to be rearranged to alter the order of the events. Every page presents a situation that goes wrong, like your spy being shot by a policeman. By swapping panels, you can make your spy grab a pistol before meeting the agent, instead of watching him get shot and fall to the floor next to the weapon. Or I can put a ladder in his way, so he climbs to the roof and avoids a guard instead of walking in front of him.

There is no space for introspection in Framed: each panel is a fragment of a linear sequence of actions, a direct consequence of what happened in the previous scene. It’s an action movie broken down in panels rearranged in a game. Which is interesting, but doesn’t take full advantage of what comics can do.

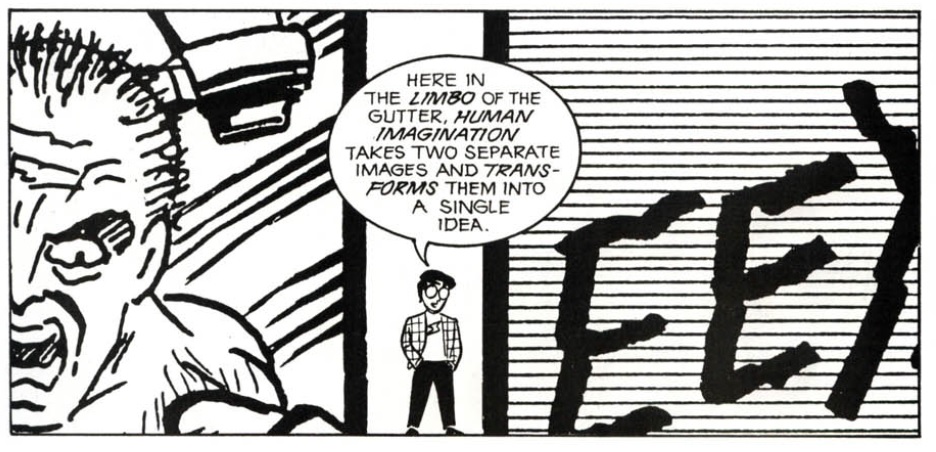

In his seminal work Understanding Comics, author Scott McCloud dedicates an entire chapter to the “gutter”, the white empty space between panels. Readers fill that void with their own imagination, connecting moments themselves. McCloud defines various types of transitions between panels. The ones we see in Framed are mostly of the Action-to-action variety: the spy shoots a guard, the guard falls. Cause and effect.

But comics don’t have to be just sequences of events. Gutters can connect seemingly disconnected images, like a rainy sky, a cat purring, a half-empty tea-cup. You are not showing an event, but shaping a feeling -- like a Renaissance artist rearranging flowers and fruits to create still life paintings with hidden meanings. And that’s exactly what Gorogoa does.

Gorogoa is not about telling a story, but about thinking about a story that had already ended. Instead of rearranging panels to form a sequence, you zoom on them, revealing new details and connecting them through the freeform association of ideas. You see a book on a library with an illustrated cover, so you click on that cover, and your panel is now an open door to a garden. Move the panel, and the door will detach, splitting the scene into two different frames. And now you have a door to put on another panel where a man is waiting, so he will walk through it and go somewhere else.

If Framed is a sequential story, Gorogoa is hypertext: a constellation of links in image format pointing to different scenes, ideas, places and times. Playing Gorogoa is like a good evening spent on Wikipedia, jumping from link to link to discover unseemingly connections.

Developer Jason Roberts first thought of Gorogoa as a comic, but quickly realized that he enjoyed the process of rearranging panels much more than the act of drawing them.

In his very good GDC postmortem, he talks about all the different meanings a frame can have: a cage, a clue, a way to highlight and preserve something. A window through space and time.

The way Gorogoa uses frames as windows is reminiscent of Here, a comic about a century of stories happening in a single room. Here is a game of puzzle boxes, where panels get filled with other panels to reveal glimpses of the past and the future. A baby plays. A man dies. A cat meowls. A couple argues. A wall gets destroyed. It all happens in the same space, during the span of a century.

The first version of Here, published by Richard McGuire in 1989, was a storytelling revolution. The author returned to the concept years later, expanding the story and filling it with colors.

The inspiration for the original concept? Computer windows, and the way they can be overlapped and resized.

Daniel Linssen’s Windowframe plays with the nature of computer windows, giving borders a physical presence in the game’s world. Need to reach a tall place? Resize the window so the character can use the border for a wall-jump. Want to cross a chasm? Resize the window and use the lower border as a platform.

The way Lindssen plays with the window frames is reminiscent of the way comics artists play with panel borders. Breaking panels is a common trope for characters aware of being in a comic book. It can be used for comedic effects, but also for mind-shattering events. Escaping the confines of a panel can be a way for characters to escape the universe, meet God, or acquire metafictional powers. If you are outside the narration, you can control it. And so the gutter, the inconsequential space between pages, becomes a heavenly space outside the confines of (fictional) reality.

As comics move from paper to screens, the grammar of the medium -- the panel, the gutter, the page -- changes shape. Webcomic authors found different solutions to cope with the digital age. Some artists prefer to draw strips in a horizontal format, because they can be easily read on a computer screen. Some prefer vertical formats, optimizing their work for mobile readers. They make long strips you can read by scrolling the page with a mouse or a finger.

In vertical strips, all rules of pages composition become obsolete. You don’t have to care about the relationships between panels, because readers only see them one at a time. But when old conventions get trashed, others emerge. Instead of representing a break, the gutter can become a literal break: the more empty space, the more it takes for a reader to scroll a page. By increasing the space between panels, you can create suspense.

Some comics previously featured in this column Lackadaisy and Sunstone, format the page differently for mobile and PC readers. The same page gets torn apart, the panels rearranged and adapted to different screen sizes.

Exactly like playing a puzzle game.