A Planet Zoo player has bred an ostrich taller than the Statue of Liberty

Biggest Bird.

There was a brief and special period, just after the launch of delightful menagerie management game Planet Zoo, during which the game’s simulated global economy went deeply and deliciously wrong. The theory was beautiful. In order to buy into breeding programmes for high-profile endangered species, players first had to prove their credentials with the husbandry of more mundane beasts. By trading healthy, happy animals with other player zoos, it was supposed, folks could work their way gradually towards the purchase of prestigious creatures like pandas, gorillas and ‘phants.

Inevitably, however, players gamed the living crikey out of the market, and - as I documented at the time - the wheels fell off with a resounding clang. Early birds hoarded orangutans and the like in vast sheds from the word go, driving most animals into stratospheric price positions, and trapping the vast majority of the playerbase in a reeking purgatory of ostriches, warthogs and peafowl. The only way out of this monotony was through quite literal brute force: by creating zoos that were little more than sprawling factories, churning out hundreds of inbred, genetically bungled animals in the desperate hope of one day being able to afford a mediocre crocodile.

Luckily, Planet Zoo was rapidly patched out of its dystopian state, and given an economic model better suited to its original, pro-conservation ethos. The pigshit-heavy ambience of the Warthog Reactor Matrices faded from save files, and across thousands of PCs, the squawking of the birdmills was silenced at last. I had thought it was all over. But in the words of the poster for Jurassic Park: The Lost World, something has survived.

I’ve been having a fantastic time with Planet Zoo of late. The recent Southeast Asia animal pack prompted me to get back into the game, and I spent my recent holiday meticulously constructing hippo zones and reptile pits with the exact melancholy fervour of Ben from Parks & Rec when he gets really depressed and takes up stop-motion animation.

In one of my recent zoos, I decided to make a big multi-species savannah exhibit, which naturally included ostriches. And while managing my flock of rope-necked ruffians into breeding groups, I started looking through their stats in the game’s Zoopedia, in order to see how my ostriches compared with industry standards.

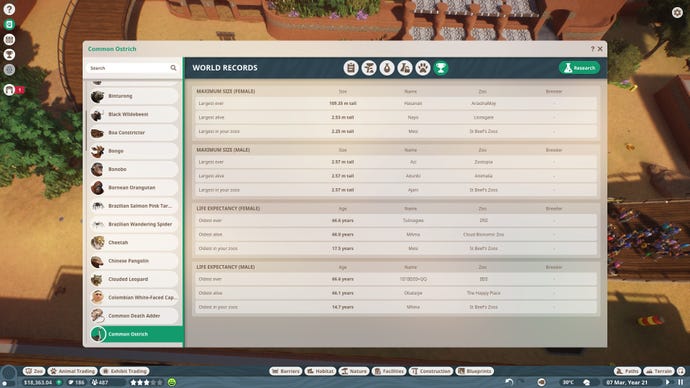

And that’s when I saw it: the largest size recorded for a Planet Zoo ostrich is 109.35m tall.

After a brief chuckle, I refreshed the page to unglitch it. But the stat was still there. All the other records on the page seemed completely reasonable - indeed, the record size for a male ostrich was a perfectly conceivable 2.57m. And yet there it was. At some point, in a zoo called AriadnaMay, there lived a female ostrich called Hasanati, who was taller than the Statue of Liberty.

Had Hasanati, I wondered, been the last in a line of titans, bred during the feverish gold-rush days of the early grind? Had she been a one-off? Or had her eldritch bigness gene been a curse passed through generations, making the mothers of her line progressively larger until they reached this towering stature?

"She must have spent her short life lying in the dust like a wheezing, feathered hill."

Surely, Hasanati’s comparatively thin legs could not have supported her colossal weight; she must have spent her short life lying in the dust like a wheezing, feathered hill, having dump-trucks full of grain tipped down her gullet. And then, at some point, with a sound like an anvil being dropped on a five-foot-thick rubber sheet, her heart must finally have caved in beneath the weight of God’s contempt, and she must have died. Her like will never be seen again, in this age of the world.

After this revelation, I began to check the other zoopedia pages, looking to see if many other species had been bred into megaton abominations. Curiously, however, everything on all the other pages seemed entirely within the bounds of natural law. With two notable exceptions.

First, I present to you Maharini: the largest ever Komodo dragon in Planet Zoo, at precisely 0.00m in length.

As was the case with our unfortunate ostrich, whatever ghastly blood ran in Maharini’s veins only afflicted the female side of her lineage, since the records for male Komodo dragons all appear quite ordinary. But unlike Hasanati, Maharani managed to reproduce. I know this because, apparently, in a zoo known only as “🭄🭄”, another such cursed lizard still draws breath. This issue, it seems, is very much still in play.

If anything, the idea of a Komodo dragon of null size troubles me more than a kaiju-sized ostrich. Is it genuinely of zero length? Or just so small that the game cannot register its presence? Has it adapted to be able to exist at a planck-length scale, hunting quantum demons in the spaces between the strands of reality? Or is it a normal-sized beast, but made entirely of photons so as to achieve zero mass? If so, is it capable of accelerating to light speed?

None of these possibilities are, I would argue, comforting. But they are, all of them, pure light-hearted fun, in comparison to the case of Hegepa 8375_5067.

Hegepa 8375_5067 was a cheetah. She lived in a zoo called “Happy Animals”. And she was minus two billion, one hundred and forty seven million, four hundred and eighty-three thousand kilometres long. To put that into context, that’s a distance that would comfortably span the entire diameter of Jupiter’s orbit. And it describes the space where a cheetah is not.

Right now, everything in Planet Zoo’s universe - every zoo, run by every player - exists in the negative space of Hegepa 8375_5067’s digital shadow. Can we truly perceive her? More to the point, can she perceive us? And what will happen, reader, if she decides she no longer wishes to be contained?