Academic Studies Of Violence Cause Violence

There's some wobbly reporting going on today, with yet another study claiming to demonstrate a link between a young person's viewing violence, and being more tolerant of violence. Which is discussed as being about videogames. Which is a peculiar way of viewing a study that shows images from films to 22 teenagers, and demonstrates that as the clips progress their brain reacts less intensely, and not surprising since the study's authors also make the same wild leap. However, it's still an entry into the argument about whether violent images beget violence.

The study - "Fronto-parietal regulation of media violence exposure in adolescents: a multi-method study" - published in the Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience journal (one with a relatively low impact factor), has almost nothing to do with videogames. The teenagers were not monitored either playing nor viewing others playing videogames. Despite this, the BBC includes a picture of a PS2 controller, apropos of absolutely nothing in the story. But of course it's easy to make the link.

Don't misunderstand - this isn't my mad tirade because someone dares question precious gaming. If there is a demonstrable link between playing violent videogames and increased levels of violence in players, then I think it would be extremely important to expose and discuss. Because it would be directly affecting us, and in turn, the way we raise our children. But we need to base this in evidence, and not wild speculation. Which seems to be at the core of how this study is being reported by its author.

This particular study includes some remarkable claims. In this study teenagers were shown a series of clips from violent "videos", and asked to rate their response to them, at the same time as having their brain's response measured. This demonstrated that as the clips progressed, they reacted less. Dr Jordan Grafman says,

"The implications of this include the idea that continued exposure to violent videos will make an adolescent less sensitive to violence, more accepting of violence, and more likely to commit aggressive acts since the emotional component associated with aggression is reduced and normally acts as a brake on aggressive behaviour."

It's this final element, the "more likely to commit aggressive acts", that the study makes absolutely no attempt to investigate, rather stating it with links to other papers, and then stating it as a conclusion.

There's an interesting confusion of studies regarding violence in media and resulting violence in real life. The main proponent for this is a book by Craig A. Anderson, Douglas A. Gentile, and Katherine E. Buckley, called Violent Video Game Effects on Children and Adolescents (pdf). It purports to demonstrate a link between increased aggression and playing violent games. But of course there have been other studies that contradict this entirely, demonstrating only that violent adolescents are more drawn toward playing violent games.

The abstract for the new paper reads:

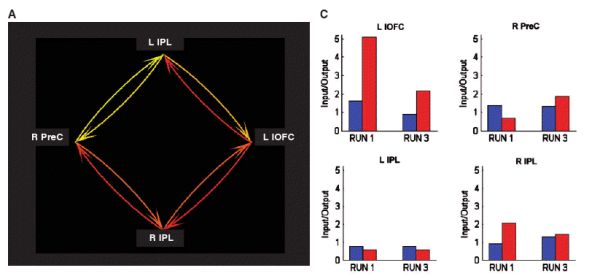

"Adolescents spend a significant part of their leisure time watching TV programs and movies that portray violence. It is unknown, however, how the extent of violent media use and the severity of aggression displayed affect adolescents brain function. We investigated skin conductance responses, brain activation and functional brain connectivity to media violence in healthy adolescents. In an event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging experiment, subjects repeatedly viewed normed videos that displayed different degrees of aggressive behavior. We found a downward linear adaptation in skin conductance responses with increasing aggression and desensitization towards more aggressive videos. Our results further revealed adaptation in a fronto-parietal network including the left lateral orbitofrontal cortex (lOFC), right precuneus and bilateral inferior parietal lobules, again showing downward linear adaptations and desensitization towards more aggressive videos. Granger causality mapping analyses revealed attenuation in the left lOFC, indicating that activation during viewing aggressive media is driven by input from parietal regions that decreased over time, for more aggressive videos. We conclude that aggressive media activates an emotion–attention network that has the capability to blunt emotional responses through reduced attention with repeated viewing of aggressive media contents, which may restrict the linking of the consequences of aggression with an emotional response, and therefore potentially promotes aggressive attitudes and behavior."

Which seems like a good start. But within the first paragraph this absolutely astonishing statement is made:

"Extensive research and media coverage have linked school shootings (Anderson et al., 2007, p. 3), real-life replications of video-game contents (Crowley, 2008) and general aggression to the exposure to extremely violent media (Anderson and Bushman, 2001, 2002)."

There has never been a single case of a school shooting being linked to violent videogames. It's just phenomenal to begin a paper with such an outrageous claim. Citing "media coverage" - the only place where such wayward ideas comes from - belies a desperation that is woefully unscientific. To call something that does not exist "extensive", and then making no direct citations that demonstrate anything of the sort, shows a bias on their going into the research.

Their results appear to demonstrate that there was a lessening of the brain's response to violence during the trial, showing four second clips of 60 muted videos of real-world violence. The 22 teenagers both physically and mentally reacted less as the clips progressed. It does appear to demonstrate that exposure to media violence causes a teenager to be - at least temporarily - desensitised in their reaction toward viewing violence.

However, there's some extreme flaws here. First is the tiny sample size. 22 isn't enough to be drawing such firm conclusions. Secondly, the extremely short time spent on the study seems very problematic. The teenagers were only tested for aggression after the test, one day later, and two weeks later. No long-term study has been used.

The BBC sought the views of Professor David Buckingham, the director of the Centre for the Study of Children, Youth and Media. He pointed out that violence is an immensely complex subject, not nearly so easily explained away. And indeed that violence is a "social problem". There is no lack of evidence that violent behaviour begets violent behaviour. This is seen in people's long-term behaviour, rather than spuriously speculated without evidence. Buckingham told the BBC,

"The suggestion is that, over a period of time, people can develop a kind of tolerance to these images - but another word for that is just boredom. This debate has been going on since before we were all born. In the 19th Century people were panicking about the effect of 'Penny Dreadfuls'. If we are truly interested in violence and aggression, rather than blaming the media for everything wrong in the world, we need to look at what motivates it in real life."

But it's hard to get the press to write stories plugging that paper.