Creature Feature: Alien - Isolation

Loving the alien

Are you playing Alien tonight? Now that Isolation has been unleashed, I want to talk about something that I brushed over in my review. It's an important thing but it's something that I didn't feel the need to dwell on because I wanted to leave a small window for everyone to have their own first encounter before I unpacked my own mental baggage. Previously, I've written a great deal about the Sevastopol, the setting, and the adaptation of stylistic and thematic delicacies from Ridley Scott's film - it's time to talk about the Xenomorph.

I made the decision to place the focus of the review on the station and its corporate calamity early. The Xenomorph has parasitic beginnings and even fully grown it functions like a poison in the system, scurrying through the arteries of the vessel and killing vital components as it goes. The context makes the creature, just as the house is an integral aspect of the spectre that haunts it.

That's why the study of Seegson and the Sevastopol is important, and why - to my great shock and surprise - I find it easier to imagine Isolation without the Xenomorph far more readily than Isolation without Sevastopol. But rather than imagining either of those things, let's look at something wonderful, something that I'd lost hope of ever seeing - an Alien game that makes the central monster terrifying and mysterious again.

The popularity part of pop culture is damaging to the scary critters and cads that make up such a huge part of it. It's easy to see Freddy Krueger as a prankster, albeit with a particularly grotesque and violent set of tricks up his striped sleeves, rather than the unnerving and literally nightmarish force of the first Elm Street film. He's likely to be seen scrapping and quipping with Jason Voorhees these days, another character who has never been as disturbing as in his first appearance. "The bastard son of a 100 maniacs", with his hideously upsetting and (hopefully) unfilmable origin, is suitable attire for a trick or treating kid, and as overexposed as a cryptozoologist's collection of photographic evidence.

We take our monsters from the ethereal flicker of the screen and the darkness of the screening room, and we defang them. Travis Falligant's Scooby Doo mashups play with that process, while also demonstrating how characters can be neatly translated into the Hanna-Barbera art style. Here's Freddy. Here's Jason. Here's something else entirely.

Creative Assembly's alien is based on the creature in the original film. At times, particularly when it's tearing open a locker, it's easy to see how a man in costume managed to portray the thing. The one major concession, the developers told me when I visited Sega to play the game for the first time, is in the shape of the legs. From beneath the tables and desks where you'll spend a fair amount of time cowering, the alien's original legs looked too much like a man shuffling back and forth. Click the joints backwards like a frustrated teenager with an action toy. make the whole setup more segmented and spindly, and the effect is far weirder.

It's not enough for the alien to be weird though. There's an expectation that it will be nigh on unstoppable as well. A perfect hunter, invulnerable to the weapons at hand, and with behaviour that is impossible to decipher. How to go about creating such a thing?

Basing a game around Aliens isn't as immediately challenging a prospect. The pluralisation acknowledges that the xenocorpses can pile high and that a few rounds from the right kind of gun will be enough to make an alien fall apart like a clumsily handled insect. There haven't just been a sequence of licensed games that cover the Aliens (and Predator) part of the universe, there have been plenty of unlicensed games that could easily fit the world with a re-skin. If there are marines and there are aliens pouring out of the walls, a splash of paint could fool you into thinking you're playing an Aliens game. There was a fairly convincing Doom mod back in 1994.

Isolation's alien is not all of the others. It's the unstoppable force and one of the game's great balancing acts is to ensure it remains credible as the greatest threat you'll ever face, while also allowing progression. The response to the creature's behaviour was always going to be divisive - IGN's review reckons its unpredictability "is both Isolation’s greatest strength as well as its most crippling weakness" (some spoilers in that link) - and it is an unusually punishing adversary. You won't need to worry about its acid blood because, to butcher an appropriate phrase, it won't bleed and you can't kill it. What you'll have to worry about are the teeth and the claws and the tail and the piston-powered mouth within the mouth. If it touches you, you're as good or dead and that's the way it should be. No QTE 'wrestle the alien' sequences here.

It's vital, then, that you have means of avoiding that deadly touch. Tools to distract, and level design that allows avoidance and cowering. Both of those things are in place, but they would be worthless if the alien didn't behave in a convincing fashion. It isn't, as might have been hoped, a persistent actor across the station, instead being attached to the player's general position like a rubberbanding car in a racing game. If it's hunting you, it'll stay close. It also moves around invisibly, teleporting from place to place for all I know, to keep the tension high.

The behaviour is credible because there are prior examples of it - it's part of the monster's modus operandi. Its previous habit of moving through vents and other hidden passageways allows Creative Assembly to shift it from place to place behind the scenes, with a clattering and ominous rumble to mark its passage, and of course the dread squawk of the motion detector. That device is another fortunate aspect of the film, perfectly suited to the game's design - it's the most useful defensive tool Amanda Ripley ever lays her hands on, and it allows the creature to move impossibly fast and to break certain rules once it breaks line of sight. Sometimes it seems to be moving through walls, in a straight line toward me, as I watch the green blip - maybe it is, maybe it's in the vents, maybe it's under the floor, maybe I'll never know how it does what it does.

It moves in mysterious ways. One day, I want to know exactly how it works and I'll probably be surprised by how sophisticated certain aspects of the process are, and how others are muddled together. Scrutinise the behaviour and you'll see the smoke and the mirrors - scrutinise the film and you'll see a man in a rubber suit. That's why the context matters and it's why, among the dark and the derelict corners of a doomed place, Giger's creature retreats from its popular image and becomes a thing to fear once again. Isolation isn't just the first game to retrieve the Xenomorph from the wars and the overexposure, it's the first piece of media to return it to its role as the solitary, sinister and unknowable thing that introduced itself to the world thirty five years ago.

Alien: Isolation is available now, as is our review.

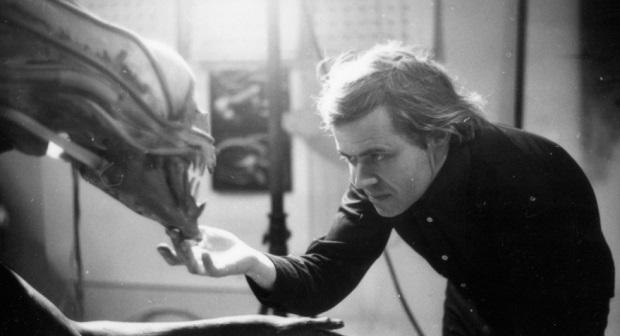

1) Image of Giger with Alien model, taken from British Film Institute (http://www.bfi.org.uk/sites/bfi.org.uk/files/styles/full/public/image/alien-1979-010-h-r-giger-and-model-00m-ymj.jpg?)itok=rbKEvfz8