Wot I Think: Always Sometimes Monsters

Not all monsters

If you’re bored of your own listless existence, Always Sometimes Monsters aims to offer an alternative. Starring a character of your choosing who is down on their luck, broke, homeless and love-lost, it’s about their quest to get their flat back, cross country for their ex’s wedding and preferably become rich and famous on the way. Naturally, I ended up a homeless loser who can’t put the past behind him, shot in the face in a ditch. Here’s Wot I Think and, much like the game, it contains discussion of a number of topics that some readers may find unsettling.

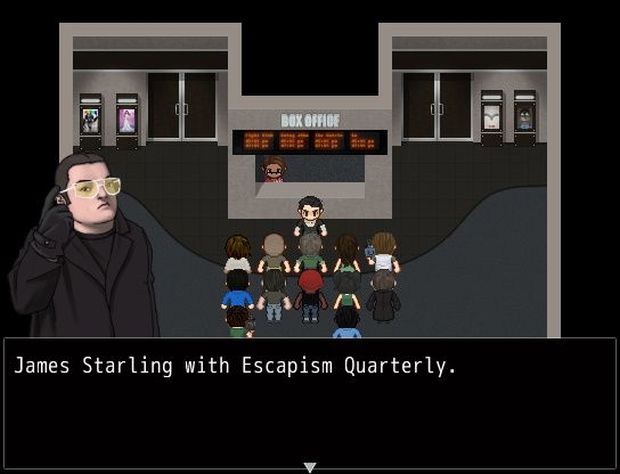

I’m not sure exactly how you’re supposed to choose your avatar in Always Sometimes Monsters, but I went for the guy I named James because he had absinthe at a party. While others wimped out with wine and beer, this was a man who didn’t piss around with lesser alcohol. Despite my legendary light-weightedness, it was something I could respect. And it is, immediately, where my experience of the game will differ from yours.

There’s a praise-worthy selection of genders, races and sexual preferences available, and each will shape the story in different ways. At points characters would dismiss James based on his skin colour, others finding some solidarity with him because of it. It’s brutally realistic in this regard, pulling no punches when it comes to the prejudices faced and privileges afforded by factors beyond our control. That on its own can and should stand as an achievement, being an idea woefully underserved in gaming.

Essentially it’s an adventure game - you’re given an end goal and must explore, find items and perform tasks to complete it in whatever way you see fit. Each chapter has the eventual goal of departing for the next main city along the road to the wedding. However, going about that is mostly freeform - just the first day gives the option of writing for a newspaper, tending bar, checking coats at a night club or running drugs. There’s only so much time on the clock, with each day broken up into three chunks of morning, afternoon and night. Different options are available at different times - characters will only be in certain places at certain times of day and may react differently depending on what has already happened or how you’ve chosen to use your time.

It’s a marvellously complex series of logic trees. They determine how you make your money, how characters are first encountered and what you may think of them. An early minor plot revolves around a rock star, his girlfriend and their drug habit. He’s worried his music’s only good when he’s high, she’s still an addict trying to give him what she feels he needs. Through the way I interacted with them both I ended up breaking into a doctor’s house and blackmailing him with evidence of his sexual deviancy. If I’d taken a different route it’s possible I’d not have even met them, nevermind the rest.

Obviously I haven’t had time to explore the myriad possible routes through all parts of the game, but stories like this seem common. There’s crossroad decisions to be made at almost every step that determine fates and outcomes. The problem comes in their significance. I’m not talking about effect this time, but how difficult it is to make those decisions. The two sides of an argument will usually be quite clearly marked as “good” and “bad” by their actions. One will lead to someone’s death or other horrible fate, while the other is more rational. There’s no Catch 22’s like the end of most Telltale episodes, just the possibility that you’ll be left with a little less money at the end of that particular string.

Which wouldn’t be a problem if the mechanical end of the game didn’t fail to hold up the emotional one. As a game built in RPG Maker, it’s played fully top-down with a basic interface. This isn’t a problem, but it makes moving around the world and interacting with characters purely an action made interesting by the strength of the writing. It becomes an issue with the introduction of mini-games. There aren’t loads, but every time they appear is another horrible downturn. Two stick out in my mind. First, a Frogger-style game meant to simulate hacking, which is as frustratingly dull and repetitive as it sounds. The other is a “combo-boxing” game that involves blind-picking from a set of rock-paper-scissors-style counters and counter-counters against an opponent doing the same. Each has a preferred set of tactics, but guessing is the fastest route through and all are too random to make a more strategic approach appealing.

Perhaps what’s worst is the mandatory nature of it all. If these were side-amusements they’d be a footnote, a joke to criticise as easter egg games have been since Doom 3, but they are pivotal to various points in the plot. While most of your time is taken up speaking to characters and deciding to help or hinder them, these are the only interaction that feel classically “gamey” and the product as a whole suffers as a result. Stripped of these you would have something different, but I think superior. The path of an interactive novel may have been preferable, removing all but the most basic interactions and allowing the excellent art to take center stage.

What this would also emphasise is the mostly fantastic writing. When not being heart-rendingly moving, particularly in the flashbacks to the main character’s lives together, it’s hilariously funny and down-right smart. There’s so much territory covered - from journalistic and medical ethics to the inner thoughts of depressed teenagers in the first chapter alone - that it’s incredible it holds together as well as it does. Individual lines had me howling with laughter, particularly in the early stages, and it’s almost enough to recommend the game on its own.

Sadly, the broader strokes are a little less easy to enthuse about. Tonally, it’s all over the place. The humour took me by surprise just because of how seriously the game presents itself and how serious many of the issues involved are. You’ll be laughing along with the self-inserted developers in the coffee shop one moment, then dealing with the results of drug abuse the next. The first antagonist, your landlord, is comedically grumpy: a Disney-villain-level of money-grubbing and youth-hating - but he’s forcing you to live on the streets until you can work off your debt. There’s a particularly interesting story in the second chapter surrounding a workers strike which is interrupted by two people literally shitting from several stories onto your boss’ car. The switches from adult themes to juvenile humour are thick and fast, making it impossible to ever be sure the smile or frown has totally disappeared from the writer’s face. It didn’t necessarily reduce my enjoyment of the writing, but did make it more jarring.

It’s something of a wasted opportunity that many of the scenarios, particularly towards the end of the game, become so ridiculous for the main character. So few games are willing to ground themselves in our own universe, in our own time, that not simply sticking to that is a failing. There was potential for a properly identifiable set of stories here that is somewhat wasted by an unrealistic raising of the stakes. There's also problems of particular threads not seeming to lead anywhere, since you depart from towns before the results of many of your actions can resolve thoroughly.

As the plot progresses, the weakness of the framing of it becomes apparent. I experienced a real disconnect between the motivations of the character I was playing and my own. I was making decisions not based on what he may have wanted, but on my own desire to see how they played out. There is an extraordinary amount of untold backstory to the situation he found himself in at the beginning of the game, and while some of it is shown, he still felt like a character I had not wholly created. He is not a clean slate to begin with, so it feels odd when I’m asked to determine how he feels about decisions he’s made in the past. Again, it's jarring rather than inexcusable, but the problems do begin to add up.

Much like life, Always Sometimes Monsters is brilliant but flawed. There’s strong stuff in there, made only better by its rarity within games. Those who have experienced homelessness, extreme poverty, lost love or most other hardships will likely find something to identify with. There’s a soundtrack to rival Hotline Miami chilling throughout and some of the illustration is superb. But there will be times when its minigames will remind you there isn’t a good game under all that writing, and the repetitive money-grinding activities required for better endings will anger, even if intentionally. You’ll love it until it drops its own name egregiously into a climactic finale or hate it until it makes you laugh and cry.

You can grab Always Sometimes Monsters on Steam or through Humble.