Cyberpunk's creator on helping CD Projekt Red stay true to the genre's real meaning

Body horror, game design and the grimbright future

During my conversation with Mike Pondsmith, two people ask him to sign artwork from the Cyberpunk pen and paper game that he created. He tells me "it never stops being weird”, the fact that people want his autograph, but he gets it. Cyberpunk is cool, it's rebellion, it's sticking an augmented finger to the system. And it's not just an aesthetic.

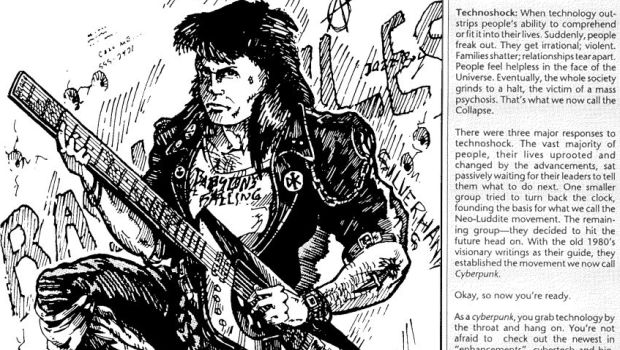

“At core, unless you have the meaning behind the black leather and the neon, you lose what cyberpunk is. That's the problem with getting Cyberpunk made as a videogame; people don't get it. They think it's about action heroes quipping as they take down corporations.” Over the years, Pondsmith has made deals with companies to bring Cyberpunk to PC but says he's glad that those deals “crashed” because now the real deal has arrived. CD Projekt Red, the studio behind The Witcher and upcoming Cyberpunk 2077, “get it”. “They're actual fans and they know stuff about Cyberpunk that I've forgotten.”

The future's looking bright then, even through the obligatory shades.

If I could have one person running an RPG campaign for me and my friends, it'd be Mike Pondsmith. He's been living and breathing this stuff for years, and he's a born storyteller. At one point, I mentioned that I'd been told he owned a lot of guns and he explained that he liked to fire guns because it's important to know how they feel when figuring out combat mechanics. The guns, like the many books that he owns, are part of a library of information to be translated into world-building and systemic game design.

But they're also weapons, and they're not the only ones in the Pondsmith home.

"I wanted a house that was hard to find. On the web and in life, I don't like to be traceable, so I wanted a place that people couldn't look up very easily. It's in the woods, you won't find it on Google Streetview, and nobody has any reason to come by unless they know I'm there.

"One day I looked out of the window early in the morning and there was this guy out front. I kept an eye on him and he wasn't moving. I didn't know him so I figure he has no good reason to be here, so I got hold of a katana..."

We'd been talking for long enough at this point that the casual katana barely registered. Of course Mike Pondsmith would have a katana close at hand in case of intruders, I thought. The day I met him he had a Millennium Falcon stud through his ear. The day before there had been another favoured pop culture reference hanging from the lobe. Like Cyberpunk itself, Pondsmith is nerdy as heck but shot through with a slightly unhinged sense of cool that he carries well, even though his particular cool is either very forward-looking or a couple of decades out of date. In conversation, he's part professor, part excitable enthusiast. He laughs a lot, often at his own lines, but is serious and sincere behind that.

He'd be a great person to have around an RPG table so, yeah, if I could have one person running an RPG campaign for me and my friends, it'd be Mike Pondsmith. But if I had to fight one RPG designer with a katana, it would be just about anybody else.

"I didn't have to use it but I was prepared to," he says when I ask how the encounter ended. "He had just got back from a tour in Afghanistan and had somehow managed to look me up online and wanted to tell me how he and some of the other guys had played Cyberpunk out there, and how much it meant to him."

One of the stories I shared with Pondsmith was far more mundane but it helped me to get to the heart of what Cyberpunk means to him. We met at Gamelab in Barcelona and a couple of weeks earlier, right before E3, my phone had died. I had to buy a replacement in the airport before the flight out to Los Angeles and anyone who has been on the verge of a long trip and finds themselves suddenly without their most-treasured gadget can no doubt sympathise. Without it, I didn't have access to maps, hotel details, contact numbers and emails for appointments, or even the boarding pass for my flight. It's only when I'm suddenly without a phone that I realise how much I need it.

I mentioned this to Pondsmith as we were talking about anxieties around reliance on technology and I used my former phone as a convenient example.

“But what did you do?” He asked.

“I bought a new phone. I had to.”

“That's cyberpunk. It's not just about the tech, it's about the ubiquity of the tech. If augmentations are rare, if they make the people who have them special, that's not cyberpunk. It has to be street level. It has to be everywhere and available to almost everyone.”

The phone anecdote might have triggered this central idea about cyberpunk, but before we dug into body horror, the ubiquity of tech, and real world social and political parallels, we spent some time discussing exactly what CD Projekt Red are doing with Pondsmith's fictional future, and how he's contributing to the game.

“What happened was, around four years ago they called us up and I'd never heard of them. I was imagining a tiny studio out in Poland that had done very little, and then I looked at The Witcher 2 and thought, “Wow. This is good. This is really good.” So I flew out to see them and realised they were genuine fans of Cyberpunk. What they didn't realise is that I've worked in design on the videogame side as well as tabletop

“At the beginning of the project, I talked to them a lot, every week. For a long time they didn't realise I'd worked in digital, but I've been doing pen and paper for 20 years and digital for fifteen. When I was explaining Cyberpunk to them, I was explaining the mechanics in a way that they understood and that helped them to realise I could contribute more to the actual design.

“Now I do a lot more meta-talk to the whole team, to make sure that they get the gag and they know what the touchstones are. From there I got involved more in actual gameplay mechanics; what can we get away with. We had a discussion at one point, for example, about flying cars. I have them in cyberpunk because they are a fast and efficient way of getting characters from one end of a ruined city to another. And trauma teams are there because we don't have clerics.

“But what happens to these things in a digital, three- dimensional environment. Flying cars are cool but they're not there for flying car gun fights. It's not their place in the world. They're a convenience in the design and like so many things in Cyberpunk they have a mechanical function rather than just being there because they're cool.

“So a lot of the conversations we've had on the team are not "can we do this?" We can do just about anything. Instead, it's me explaining why I did it in pen and paper, and then we figure out if we need it again, and whether it serves a different purpose in a videogame. I know why flying cars are there in the original but that's not necessarily the same functionality we need in 2077. Everything is taken apart in terms of what it does to the game, how it differs from tabletop, and getting the right feel.”

It was news to me that Pondsmith was having this kind of input on Cyberpunk 2077, alongside his work on a new iteration of the tabletop game. The new pen and paper version, coincidentally codenamed Cyberpunk Red before any contact with CD Projekt Red had occurred, will be set in 2020, decades earlier in the timeframe. Because the two games are in the same continuity, there's a back and forth about narrative aspects that need to match in a credible way. Pondsmith has had to tell the 2077 devs that certain characters they might want to use will be dead and forgotten by the time their story begins, although he smiles, saying “I do have ways to bring some of them back”.

But the tone and meaning of Cyberpunk 2077 is harder to capture than the specifics of individual characters.

“One of the things I love about cyberpunk as a genre is that there is a romanticism to it. There's a sincerity. Even now, cities are romantic. Me and my wife were staring out over the chasm of the city one night and seeing the neon and hearing the sirens, and when you're there, you're aware of this whole manic aspect living underneath you. The addition of these new technologies just gives it a bigger impact.

“It's about more than big guns and leather jackets. Walter Jon Williams wrote the book that really got me into this, Hardwired. It's total whack-out fable of doomed romance against desperate stupid odds. You know it's not going to work but you really hope that it does, and that's what cyberpunk is all about.

“It's constantly evolving though, as a genre and I don't feel any ownership of it. Take Ghost in the Shell. The new movie is not Standalone Complex, which is not the original Ghost in the Shell. Then there's something like Appleseed, which is what we will get if we manage to survive what's going on in Ghost. They're different kinds of cyberpunk - a lot of the Japanese works have made me feel more about what defines it. Believable technology and a callous universe of people more powerful than you who are so powerful they're faceless. It's about fighting for your piece of ground so you can have a life. Cyberpunk heroes aren't trying to save the world, they're trying to save themselves.”

I'm interested in the idea of faceless villains, though I'm not entirely sure 'villains' is the right word. Pondsmith uses Blade Runner as an example.

“We never see the face of power in Blade Runner. Instead, we see an errand boy, Gaff, but we never see the top level. And Deckard doesn't think about what he's doing, he doesn't really question it. Some power that is tells him to kill replicants, who might well essentially be people, but the whole point when he leaves with Rachel is that he doesn't save the replicants. He saves Rachel and goes away. That's not a hero's tale. That's somebody saving his skin and the skin of someone he cares about, but it's very cyberpunk. That idea of feeling that the chance that we have with each other, and the chance of a better life, is worth incurring the wrath of these unseen and mighty powers.”

But Blade Runner's cyberpunk isn't Pondsmith's Cyberpunk. He likes Blade Runner though, which is more than can be said for a lot of the sci-fi movies we end up discussing. He likes internal consistency, particularly when it comes to tech and the ideas behind that tech, and it's something he thinks writers often sacrifice for a thematic punch, or to move a plot. When it comes to games, he's critical of Deus Ex, though not so much because of any specific aspect, but rather, I think, because it's worryingly close to the game Cyberpunk might have become in the wrong hands.

“I like a lot of the things that are going on there but the main characters are special because of the technology so it's very far from street-level cyberpunk. The tech shouldn't make you a hero, it should just be a part of ordinary life.”

This bring us back to my dead phone and the ubiquity of technologies that were so recently unimaginably powerful.

"If you lose your phone, or it dies, then you just replace it." Pondsmith says, waving around his own smartphone, which is currently pinging him real-time information about seismic activity somewhere in South America. "I'm plugged into the planet with this thing. That's how amazing it is, but the tech is everywhere. It took me about an hour at most to re-establish everything that had been on my old phone on this one when I bought it. Information and preferences are easily transferable."

I think there's a deeper issue though: even if I can replace the phone, I don't control the networks and the satellites that allow the phone to operate. So much of the power isn't in the phone, it's in the access that the phone has, and that is not replaceable. Not by me at any rate. If my provider cuts me off from data and telecommunications networks, I own a very expensive brick that can play match-3 games.

“Think of it in the context of net neutrality, which is really about corporations not wanting people to have access to other people. Within six to eight years of net neutrality crashing and burning, if that happens, we'll end up with an alternate net. You might not be able to build it yourself, but somebody will create it and provide ways for you to access it. The upshot of the ubiquity isn't just that you can buy a thing or access it through official channels, it's that when those official channels are taken away, or censored or throttled or controlled, somebody will always replace them. People will make alternate forms. It even happens with currency. Look at Bitcoin; it's money that the government doesn't necessarily control.“

To build his vision of the future, Pondsmith has absorbed knowledge about technology, futurism, politics, social trends, fashion, geology, and just about any other topic you might care to mention. A designer's library, he says, should be deep and broad.

“We're just having two new bookcases into the bedroom, which will mean every wall contains books, and that's on top of an entire room devoted to books downstairs, and the ones stored in the office. It's paleontology, a hobby of mine, to human history and everything in between. Part of the reading is building knowledge, but it's about trying to get a sense of the zeitgeist: what is going on, what is visible, what will give us certain outcomes.”

I asked if finding the zeitgeist had become easier now that there's so much data to dig through, or if all the noise made finding a clear signal harder than it had been in the eighties, before information clogged the air that we breathe.

“What you have to do is go outside your bubbles. The more dataflow you can stand in, the more you can learn. I hit reddit and twitter, and do a lot of lurking. There are only three places where I let people know who I am, mainly so that I can get a reaction from fans and people who are interested in our work. I can learn a lot by going to a store, looking at the magazines people are reading. I can learn a million things by visiting a toy store. These are the ideas the next generation will grow up with.

“The internet is important too, of course. I spend a lot of time trawling for information, checking things and going down rabbit holes. But you expose yourself to a lot of terrible things as well as wonderful things out there. I had a really nice young woman who was my social media person and she almost had a breakdown dealing with it. The biggest advantage you can have out there is to be unflappable. That helps. The most horrible voices are usually the loudest because they have no other place to yell.”

All of that noise, the yelling and the disenfranchisement included, often seems symptomatic of a peculiarly modern mania. Does Cyberpunk have to reflect the times we live in, and the geopolitical changes from one edition to the next?

“Cyberpunk Red has an entire bunch of sections that say '2020 is closer than you think'. I talk about ramifications of what we are doing now. This is my son's reality and future, and unless we start straightening our shit out, it's not going to be pretty. There is a strong political undercurrent in Cyberpunk, but the biggest message is simple: if you want a future you have to take it into your own hands and realise that nobody else will build it for you. That may involve political action, hacking, or picking up a gun. But the future doesn't come out how you want it unless you make that change."

Another central tenet of Cyberpunk, Pondsmith tells me, is that “even if a cause is doomed, you need to fight for it”. Indeed, the Cyberpunk world is full of people striking against what they see as misuse and abuse of power, whether in the form of ecoterrorism or anti-corp hacks and assaults. The line between freedom fighter, survivor and terrorist is blurred.

“There are some eerie parallels in things I've written about terrorist attacks and situations in the real world, but if you follow the trends as you write about the future you're probably going to end up a place that is sometimes painfully familiar. But Cyberpunk is a parallel future rather than a prediction of our future. Terrorism comes about when you have people who want to fight someone but don't have the means to fight them except through these acts. These situations aren't new – they could reflect 19th century India, mid-20th century Europe or 21st century America.”

But whether these futures are parallel or predictive, Pondsmith doesn't think we're far from our very own cyberpunk lifestyle.

“The thing of it for me is that it all boils down to people and how they use tech. It boils down to tool-use and that is the extension that makes us kind of meta-creatures. You remember things on a much larger level because you have memory devices. At any minute you can get a story and translate it into five languages, then throw graphics behind it. You have access to these insane tools.

“Part of what's happening now is that these tools are becoming accessible to more and more people; across history, powerful creative tools have been the promise of the very few, like the printing press and even paper and ink. Benjamin Franklin said “the power of the press belongs to those who own one”. Well, a whole lot of us own things more powerful than the printing press now.”

But how far away is a device transmitting information and providing access to tools from actual body augmentation?

“Body horror creates an interesting cultural sliding point. Once we get over the body horror aspect though, we'll be happy to have it all built-in as long as, once again, it's easy to repair or replace. One of the things about the cyberpunk culture is that we're not going to get man-machines because we want to turn ourselves into robots; not in terms of jumping fifty feet in the air or punching through a wall. It'll happen because we want more choices, more knowledge and more access.”

So no bionic arms then?

“I didn't say that, but I certainly wouldn't be first in line. My kids might though. The idea that I'm going to cut my arm off all the way to the elbow and replace it with metal is...” he shudders. “But the tipping point is already gone. Old people have artificial hips, my mother had surgery to remove cataracts and now her vision is better than it was before the cataracts.

“Eventually the transgressive nature will be reduced. An entire new thing right now is 3d printing to build prostheses for kids that lack limbs. Well, somebody who has a silver-chrome cyberlimb like [Cyberpunk character] Johnny Silverhand might tempt some kid who isn't missing a limb to have their hand removed just so they can have a better one. Like Johnny's. At some point, when that process is easy to do, it won't seem like such a big deal.”

Pondsmith introduces me to Aimee Mullins, through the medium of a TED talk rather than in person. I'll leave you with that excellent talk, but first a word about a familiar character.

“I think Geralt is a little bit cyberpunk and I hope we can sneak something in 2077 that relates to him without the fans immediately catching on. He does what he needs to do, he doesn't necessarily get any joy out of it – he just makes sure that what needs to go down does go down. It's a combination of fatalism and romanticism. That's cyberpunk.”