Disco Elysium’s Hardcore Mode is just one way games can meaningfully explore poverty

Month at the end of the money

Last week, the haunting and hilarious Disco Elysium added an extra difficulty setting called ‘Hardcore True Detective Mode’. On the surface, it seems like a fairly standard set of tweaked parameters. More demanding dice roles to shaft dear old Harry Du Bois at every opportunity.

If you take time to read the update notes though, it becomes clear that these new changes are storytelling devices as much as adjusted sliders. Since there are no monsters to make tougher, it’s your wallet and psyche that take the hits. It’s had me thinking about how ZA/UM’s surrealist cop odyssey, and other games, express poverty through their systems. Games that invert the traditional power curve of farmhand to godhood, or make us try twice as hard to get half as far. Far from being a detached add-on, the update is a deft application of mechanics-as-metaphor that wouldn’t work if desperation, isolation, poverty, and addiction weren’t already stitched deep into the fabric of Disco Elysium’s fiction.

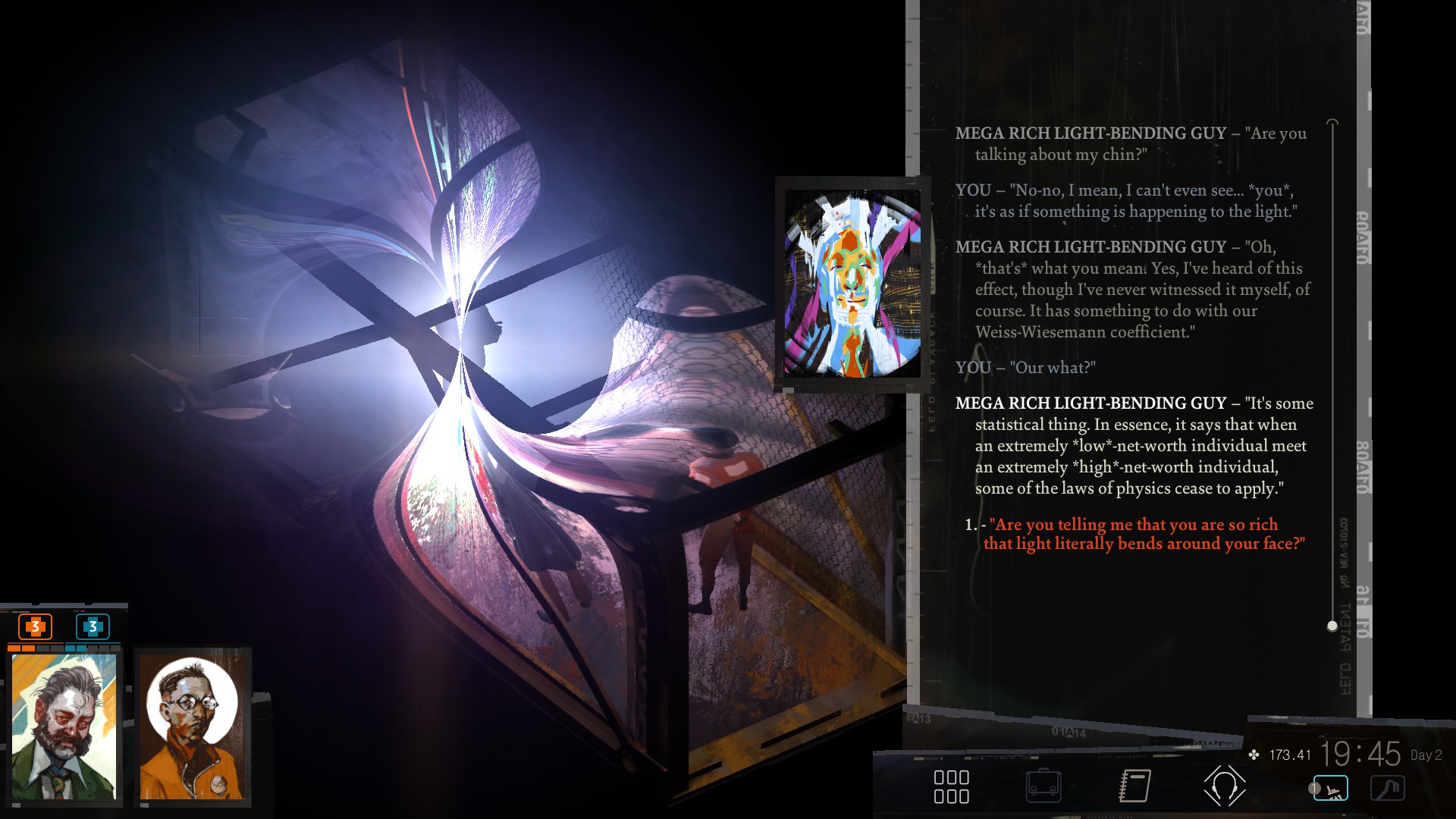

Time was in Disco Elysium, you could just ask a light-refracting millionaire living in a storage crate to invest in a business you made up on the spot, and that was you sorted for the rest of your trip to Martinaise. Hardcore Mode makes réal scarce. Filling plastic bags with empty bottles goes from amusing busywork to a near necessity.

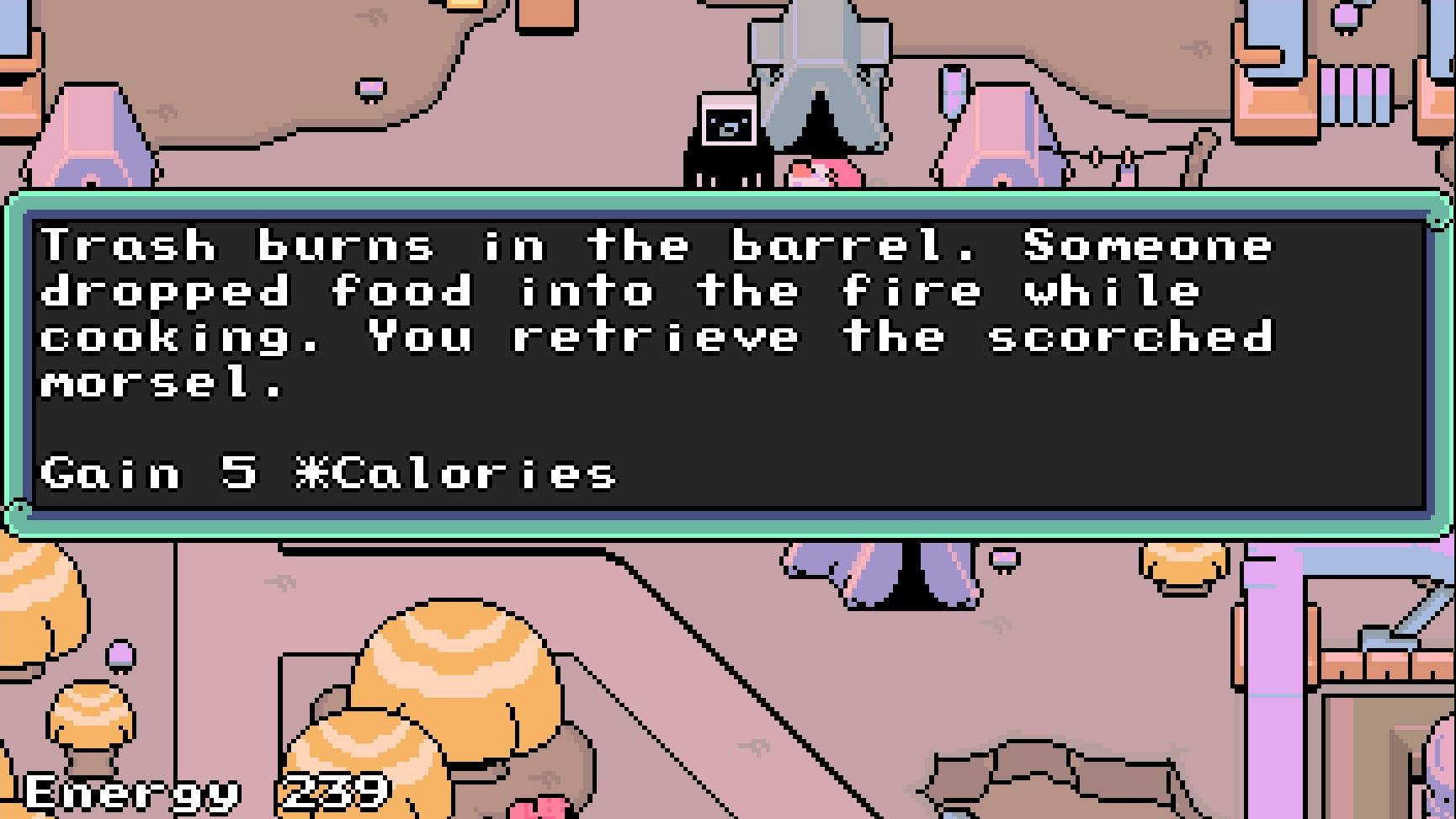

Nominally, at least, this is familiar RPG territory. There’s little functional difference between hawking loot to the village shop, and selling tare for pocket change at the 7-11. The glory from slaying ten goblins just isn’t there if instead you’re fishing ten bottles out of a bin, though.

The archetype of the fearless adventurer becomes a new kind of fearlessness: the type that knows whatever the locals mutter about Harry’s dumpster diving is water off a thrift-store raincoat. Compared to the very real gnawing in his gut, or the morning shakes, or the screaming spine from a night spent sleeping on a metal bench.

With pharmaceuticals raised in price, self-medication often becomes the more attractive option. Disco Elysium stands out here by not demonising drugs from the outset, instead portraying them as both a good time, sometimes, and a symptom of economic desperation.

“Drugs don’t make people abuse them,” says Ruby the gang leader, when you finally find her. “Hopelessness does.”

Disco Elysium feels that much more honest and powerful for its refusal to cartoonify, mystify, or condemn the drugs that feature so prominently in its systems and story. I’m reminded of the Witcher’s Fisstech, and Skyrim’s Skooma. In both these games, taverns flow with delicious, harmless ale. Every other substance is - in a rhetoric reminiscent of so much damaging drug legislation in our own world - lumped into a single category, and given a lone, unambiguously bad fictional analogue.

Speed is speed in Disco Elysium. I might know someone who, aged seventeen, did far too much speed and stayed awake for four days, watching peripheral shadows flicker and grinding their teeth to dust, contributing to a mental breakdown. That person might be me. It’s awful shit I’d recommend to absolutely no-one, and I love how Disco Elysium handles it.

Depending on where you grew up, a used lottery ticket full of catpiss-smelling chemicals is often easier to get delivered than a takeaway pizza. In Disco Elysium, such chemicals are made fun of, demystified. Normalisation doesn’t have to equate to endorsement. Harry is a joy to play as, but he’s also an absolute shambles of human being. Drugs can be hilarious or tragic, beautiful or destructive. Portray only one side and, much like the book murderer, you’re missing half the story.

It’s not just full blown addiction this deals with, though. By tweaking a few numbers, Disco Elysium emphasises the small pleasures we rely on to take the edge off. With the stat bonuses they provide becoming more precious, the odd beer or cigarette becomes, as they so often are, a fortification against whatever tedious nonsense the day decides to hurl at you.

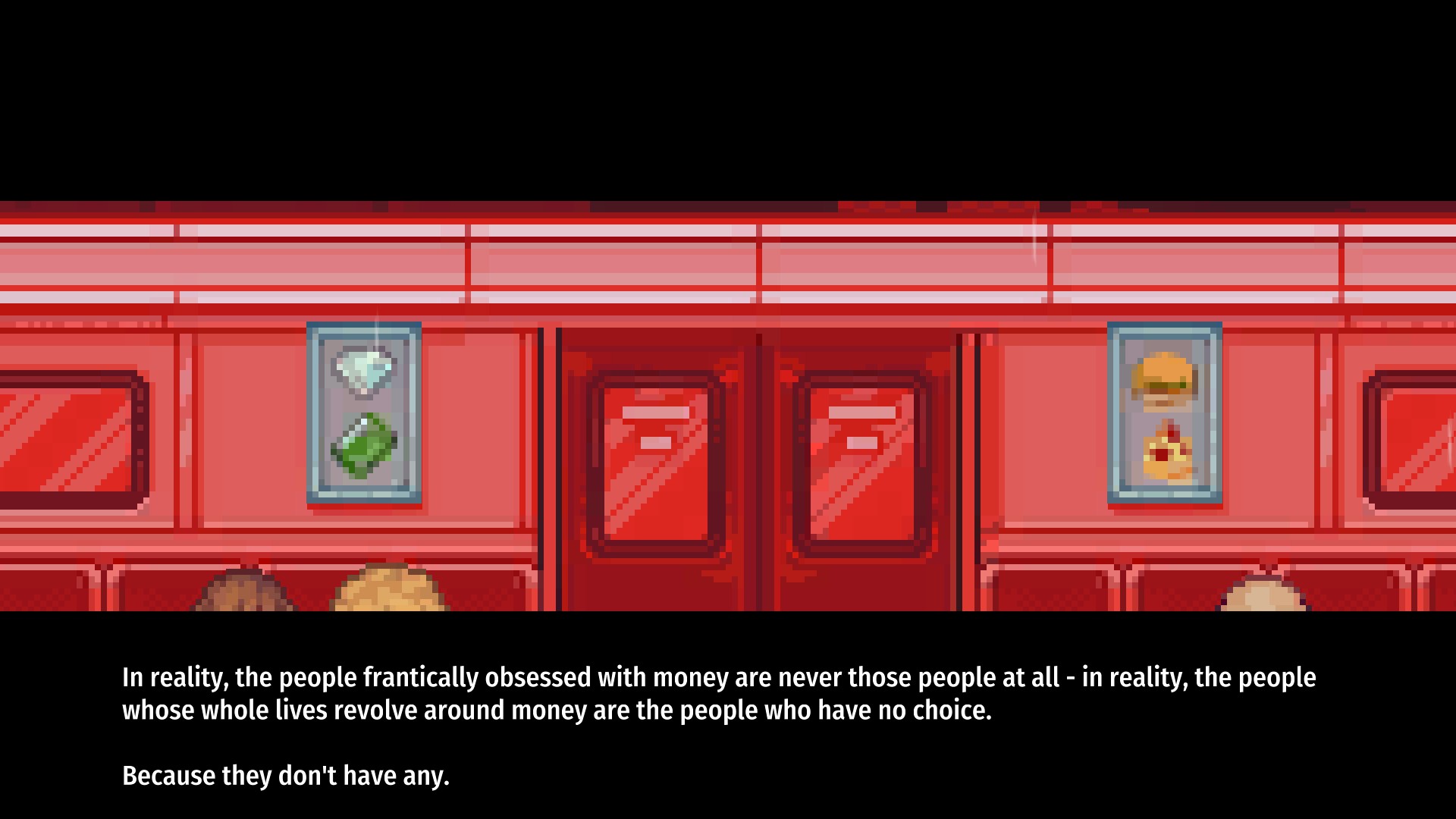

These tiny vices are everywhere in Martinaise. Minute pleasures not as hedonism, but portable fortresses. Self administered splashes of colour to combat the depression outside and in. The poor have been long demonised by conservative pundits for their apparent decadence, even if they pale in comparison to the excesses of the wealthy. Champagne and cigars are markers of refinement and success, but roll a smoke on your lunch break, or a glass of two-for-one cornershop wine after dinner, and you’d better believe you’re on the rocky road to addiction and ruin, you slovenly shitmuncher.

So called ‘poor laws’ - and the related justification rhetoric - have a recorded history in England reaching all the way back to the 1351 Statute of Labourers act, which made it illegal to pay peasants more than they would have received pre-Black Death, despite food shortages and the subsequent inflated prices. A source quotes farm-owner John Gower as saying, in 1360:

"The shepherd and the cowman demand more wages now than the bailiff. They work little, dress and feed like their betters, and ruin stares us in the face."

I’d pull up a comparable Daily Mail headline here, but you already know them: you can't afford a house because you gorge on avocados and weed every hour God sends. The poor have long been lambasted for having the audacity to indulge in anything a bit spicier than bread and water. Although Disco Elysium shows us - in characters like the lovelorn alcoholic Idiot Doom Spiral - the pitfalls of allowing altered states to fill the indent of absent human connection, a focus on socio-economics develops a world where the lack of social safety nets and meaningful employment is a harsh rejoinder to neoliberal canards like ‘personal choice’ and ‘meritocracy’.

Harry’s colourful menagerie of lost-and-found garments take on a new significance, too. During my second playthrough, I delayed every skill check I could just to deck myself out in whatever clothes from my ever-growing sack of oddments would best serve the situation. In hardcore mode, this is often necessary.

In a 2012 paper from Northwestern University entitled Enclothed Cognition, authors Hajo Adam and Adam D. Galinsky explore the "systematic influence that clothes have on the wearer's psychological processes." The paper includes studies where participants wearing lab coats were shown to be significantly more perceptive in a variety of visual tasks. The paper builds on a long history of similar studies where, for example, teaching assistants that wear formal clothes are perceived as more intelligent, or that sports teams dressed in all-black play more aggressively.

If you’ve ever managed to find an absolute steal at a charity shop on a tight budget, though, this should all be familiar. The way a vintage coat you picked up for under a tenner can tie together an outfit of budget clothes is pure magic. It can make you feel like you belong in a crowd, even look good. You move more freely, rather than being weighed down by the self-consciousness of being clad in outward signifiers of what, on the worst days, feel like profound personal failings.

Disco Elysium isn’t the first game to tackle these themes, of course. Post-Brexit dystopian doorman sim Not Tonight expresses poverty in terms of the numbing grind that goes hand-in-hand with precarious employment. Living in a crumbling flat, with a tiny heater and crackling electrical sockets, you take jobs from an app named ‘BouncR’ via a perpetually cracked phone screen. You don’t have to sell drugs to get by. But also, you start the game with a water bucket instead of a fridge.

Night In The Woods, which explored US rust-belt poverty and alienation through hauntology, places much importance on friendship and community as a panacea for economic isolation. It’s all dialogue and exploration, sure, but the more the conversations you seek out - the more stories you take the time to listen to - the less alone and more part of a community of folk going through the same issues you feel.

In last year’s Alien Squatter, you begin the game as a homeless alien living in a tent city inside an abandoned dairy-themed amusement park. You’re forced to strangle pigeons for food, and search through bins for scrap. Energy is your most important resource, with each step draining it away. It makes you feel constrained to your stamina in a way I haven’t quite experienced before. Our own energy becomes such a special and precious thing to us as soon as we notice it slipping. Hustle culture - like old mate John Gower the farmer - tells us that if we’re not producing our daily twelve bushels of graine for oure lorde, we are but useless counts. I’d love to see more games treat stamina not as a secondary health bar, but as inexorably linked to physical and mental well-being as it often is.

Narrative adventure Little Red Lie stands out by calling into question the sincerity of all the pithy observations an RPG character might usually make when delivering exposition. A distance is maintained between player and character. Through this disconnect, themes of powerlessness are reinforced.

"I think games are an inherently great medium to explore powerlessness, both as an individual and in society," Little Red Lie developer Will O’Neill tells me over email. "Players expect agency within them, so when you that away I think the contrast is more sharply felt than it would be if you were simply witness to it as you would be in a movie or other medium."

O'Neil says that in a story-driven game like Little Red Lie, players might ordinarily expect multiple forms of interaction - talking, opening, closing, pushing, pulling. "I wanted to find a way of showing how the threat of poverty and the power of money overrides anything and everything else into a masquerade, while also drawing into sharp relief the few honest moments that everyday people can still find. So I took away all those other kinds of interactions that players might expect and left them with only one: lying. It worked."

Horror games, too, are uniquely positioned to explore psychological bleakness and lack and lack of player agency.

"I conceived the project shortly after I'd lost my home due to poverty," Doc Burford, writer of Lynchian horror gem Paratopic, tells me.

"A lot of what I conceived when first working on the game drew on my experiences of living with poverty and the frustration I felt at having lost my home; I wanted to create terror through powerlessness…" Burford explains that the Power Company, the primary employer in the game, is inspired by the Koch Industries he grew up near in Wichita. Paratopic is full of references to a failing economy. "At one point, Smuggler indicates he has no real job and the Attendant suggests trying to find work in the unnamed town where the gas station is located, but then acknowledges there isn't much work to find."

“Every step of the way, the game is about powerlessness," he says. "Each of the game's three protagonists are poor, unable to make decisions for themselves because they don't have the money to do it.”

For every Disco Elysium, Paratopic, or Little Red Lie, of course, there’s tasteless shit like Bum Simulator. It might be a sweeping statement to suggest there’s an inherent tension between video games as a medium and poverty as a theme. I’m a firm believer in art being essential, not some sort of luxury you only indulge in once you’ve ticked off the rest of the needs hierarchy.

Still, I know that when I’ve been in the shit financially, the shelf of games is often the first thing to go on Ebay. There’s a disconnect between poverty and what games represent as expensive physical goods, not to mention to the systemic poverty the conflict minerals used in hardware manufacture are a product of. With power, accumulation, and conflict so baked into the design history, though, games are in a special position to subvert and challenge these values. There’s special poetry in making us feel less, not more, powerful.