Doom At 30: John Romero remembers his seminal FPS so that we don't remember it wrong

The original id Software designer talks Carmack, cacodemons, and his Native American influence

“When people read anything, no matter the source, they will believe it.” So says Doom designer John Romero on the subject of his relationship with John Carmack. Together, the pair built id Software and the FPS genre as we know it - before the cracks started to show during the difficult development of Quake, ending their professional partnership.

Yet any lasting acrimony has now dissipated. That became apparent when Romero’s new autobiography, ‘Doom Guy: Life In First Person’, showed up on shelves with a glowing back cover quote from Carmack. The latter praised Romero’s “remarkable memory”, and waxed wistfully about their shared impact on the gaming medium. “For years, I thought that I had been born too late and missed out on participating in the heroic eras of computing,” Carmack wrote. “Only much later did I realise that Romero and I were at the nexus of a new era - the 3D game hackers.”

In fact, Romero and Carmack had spoken at length during the book’s writing, chatting away on multiple fact-checking Zoom calls. “People just didn’t know,” Romero says. “It was funny when I had other people come into a Zoom call with John. Nobody had seen us together in anyone’s memory, so when they could hear us talking to each other, it was kind of a shock: ‘They’re not adversaries.’” The two Johns joked around, speaking with the familiarity of old colleagues. “People don’t know what it was like when we were working together.”

Still, Romero acknowledges that communication often broke down in the early days of id Software. “We were just these 20-somethings running a giant company that had done really well,” he says. “And it really did need to change, because we were building something way more difficult, which was Quake. It required a totally different situation, because of the other people on the team. We didn’t take that into account.” In their more recent conversations, the two Johns have talked about the ways they could have solved those issues in retrospect. “We wouldn’t have had to split up.”

Today, the two Johns have reunited for a livestream. Not to talk about their break-up, but the period before - when they were both pushing in the same direction and breaking new ground. The moment, precisely three decades ago, when they released Doom.

By then, id Software had already put out Wolfenstein 3D, and a global audience awaited its next game. “With Wolfenstein we got number one on the Usenet top 100,” Romero says, “and we stayed there for about a year, until Myst came out.” But they weren’t nervous about pressing the launch button on their follow-up project: “We were just tired.”

Much has been written about Doom in the years since. The adrenaline rush of its action, the knotty unpredictability of its levels. But an important part of the story has often been left out. Romero is of both Yaqui and Cherokee ancestry. He spent hours and hours in the Sonoran desert in Tucson, Arizona, with his Yaqui father - who taught the young Romero how to read and respect the land and its landmarks. “My culture is important to me and influences my designs, particularly my level designs,” he tweeted recently, in celebration of Native American Heritage Month. “Doom is an indigenous design.”

It’s not something he was conscious of back in 1993. “I moved out of Arizona when I was eight, to a stepfather who was German and middle class,” he says. “Basically a white family situation. I didn’t think about [my heritage]. It wasn’t ever treated differently in school, it just felt like everyone else.”

"I got thinking about, what do I want? I want landmarks I can visit multiple times."

As a result, Romero describes his Native influence as unconscious or subliminal - an inherent understanding which shaped the way he approached space in Doom. “To me, the environment is the most important character in the game,” he says. “It’s the thing that I need to make sure I’m spending the most time on, because that’s where the player lives and encounters everything that we’re putting together.”

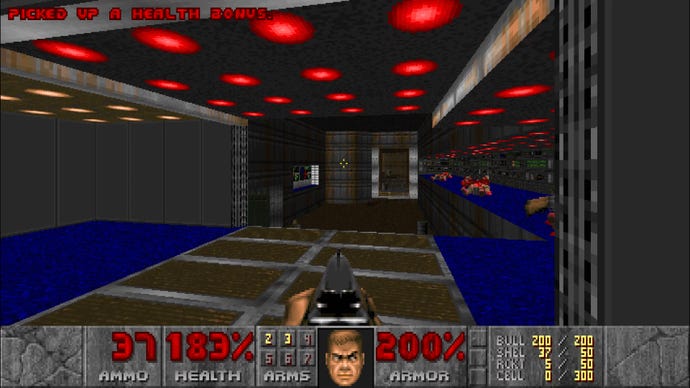

Where Wolfenstein 3D levels were made up of 90-degree corridors, Doom’s data structure allowed level designers to build vertically. “I got thinking about, what do I want? I want landmarks I can visit multiple times,” Romero says. “I don’t want to send me on some long, non-stop journey through the desert, I want to come back and see and use this place again.”

Thus the level design process Romero established in Doom tends to send players outward from a focal point, before pulling them back to that centre - ensuring they have a better understanding of the space when they come back. “In Native thinking, it’s almost like you can remove time from the equation of things that have happened in a location,” Romero says. “There are ghosts forever. Stories take place, and it’s just information that’s valuable, and it doesn’t matter when it happened.”

"For platforming, Mario’s movement is basically perfect. And I think for Doom, it’s basically the same thing."

That sense of history, still relevant in the present, is certainly recognisable in Doom. Many of its deeply abstract levels physically transform as you explore, revealing new architecture and enemies while continuing to draw on your initial understanding of how to navigate them.

It’s a timelessness that’s been reflected at a broader level, too, over Doom’s three decades of existence. There are very few games released in 1993 still played for fun by successive generations, with no need for remake or update. “Simplicity is its strongest point,” Romero says. “It still feels good. You don’t see any texture shimmy or wrongly drawn pixels in the world. The player feels like they’re in a real environment that obeys its own laws. The movement is extremely solid, even though it’s really fast. For platforming, Mario’s movement is basically perfect. And I think for Doom, it’s basically the same thing.”

Doom’s engine was min-maxed according to principles that still stand up today. In a period when framerates routinely scraped the floor, Doom promised a consistently smooth experience - just like Mario. “It didn’t matter how many things were gonna happen on screen,” Romero says. “It was always gonna draw at 35 frames.”

And then there’s the modding, which has ensured that Doom is not just playable but still living and evolving. id Software officially released the game’s source code on December 23rd, 1997 - a highly unusual move at the time. “It’s kept the game going,” Romero says. “Without the source, modding probably would’ve stopped a while ago because it’s too hard to run on Windows and nobody wants to use DOSBox all the time.”

Alongside the livestream with Carmack, Romero is launching a new Doom episode named Sigil II - nine levels constructed using a fanmade level editor. “Today’s tools are amazing,” he says. “It’s funny, because I believe that Doom level design has still not been exhausted. I’m still doing new things.”

Many of Sigil II’s secrets relate to a notorious fireblu texture from the original Doom. “It’s a bunch of red and blue dots, and it just doesn’t look like Hell, it looks like someone screwed up,” Romero says. “It’s a total meme in the Doom forums. So I decided that in every level of Sigil II there’ll be a fireblu texture that you have to find. And if you shoot it, you will open the secret fireblu room. And if you go into that room, there will be one of the lowest-level human zombies to shoot, and an item to pick up. So you can’t get 100% on the level until you find fireblu.”

This kind of playful antagonism has been a characteristic of Romero’s level design since the 90s. Each stage in Doom is the work of a singular creator, a vicious dungeon master presiding over their domain, and that’s been key to its enduring appeal. In a modern games industry where development teams are enormous, that sense of personality and connection with an individual designer is vanishingly rare.

Besides Sigil II, Romero has been working on a much larger FPS, built in Unreal Engine 5 with his colleagues at Empire Of Sin developers Romero Games. But as the title of his autobiography suggests, he’s at peace with the idea of forever being the Doom guy. “Oh hell yeah, it’s amazing,” he says. “People are lucky to have anything like that in their career. If you want to remember and talk about Doom, that is 100% great.”

Over time, Romero has embraced the role of historian-at-large for Doom and early id Software - utilising that remarkable memory to ensure he has a say in how these games are remembered. “I’ve gotten more serious about it since the early 2000s,” he says. “Because I would see things printed, not just about myself but other people's stuff, that’s wrong. They may have been writing about something that was 20 years before, but I was there and I remember it.”

Romero worries about successive generations of wrongness - the new articles based on errors that were allowed to go unchallenged in earlier works. “Correcting them is important,” he says. “Because people will use that information for books and for their theses.” As the events of 30 years ago pass into memory, Romero has taken it upon himself to keep those memories present - allowing the ghosts to live forever, as if time itself were removed from the equation.