Wot I Think: Draugen

Don't be a wet blanket, eh?

Draugen has definitely reaffirmed my belief that any era before the present was a more annoying time to be alive. Just, the logistics of it. In this case, the 20s seem to have been an absolute waste. Imagine getting a letter confirming you’re going to stay with someone, sending a letter back, and then travelling for an actual month just to get there.

And then when you turn up the entire village is mysteriously empty, and you have to spend a week sleeping on the sofa downstairs because you’re too polite to go upstairs to the guest room in your hosts’ vacant home without an invite. Jeeze, 1923, be more of a confusing post-war nightmare, why don’t you?

Draugen is partly a first-person investigate-em-up and partly a meditation on loneliness. Serious intellectual artist type Teddy and his 17-year-old tomboy ward Alice (aka Lissie) figure out what the heck is going on, old bean, by exploring, finding letters, and putting together clues. The pair is actually there to try to find Teddy’s sister Betty, an investigative journalist who came to the village for unknown reasons.

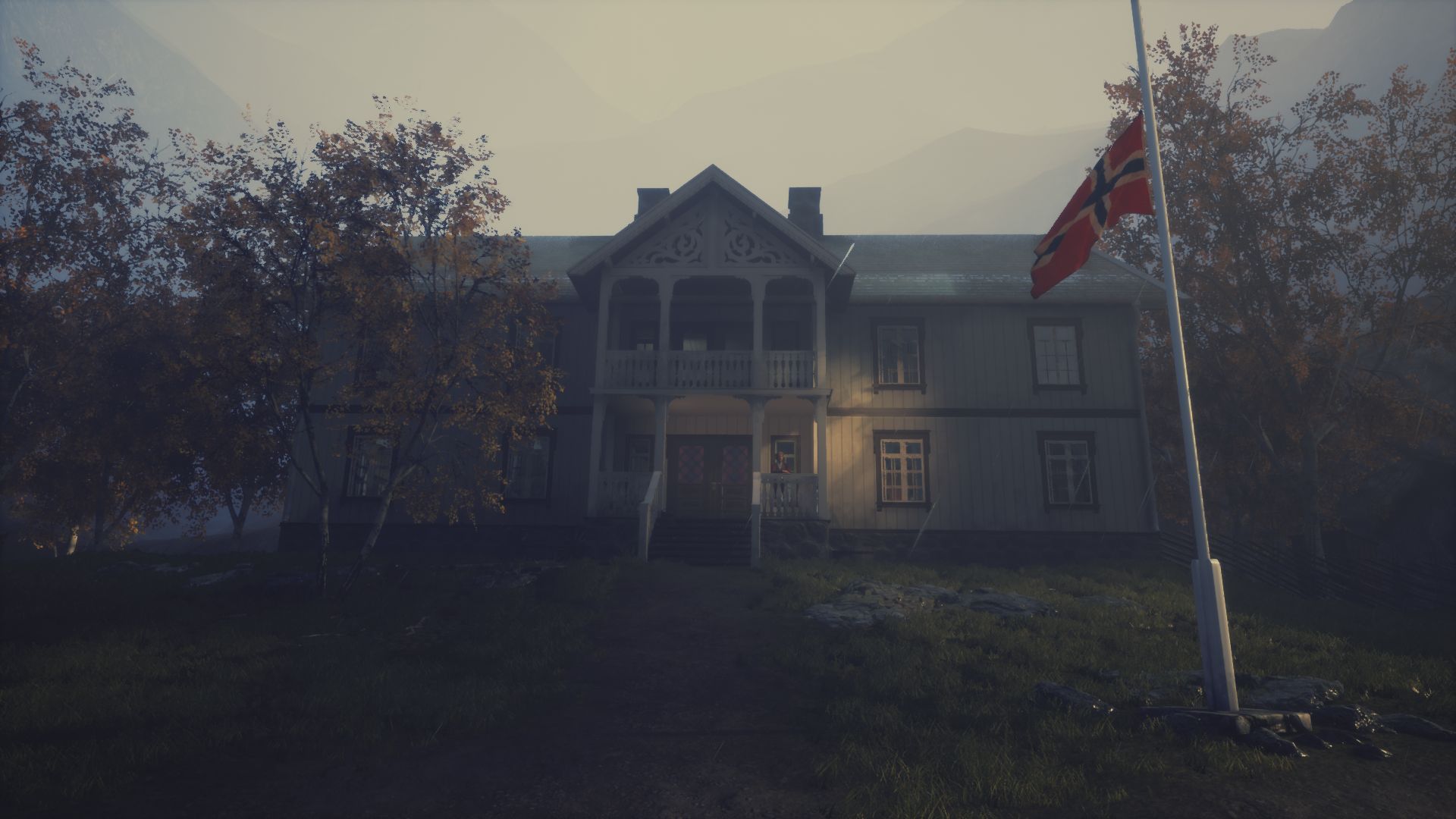

The village in question is Graavik in Norway, tiny and picturesque but nevertheless isolated and creepy, one imagines, even when people were actually living there. A handful of single-story wooden houses with mossy roofs are supplemented by a local store, a church, some fishing huts, and two big farm houses that belong to the two most prosperous families. Everyone chopped their own wood, and walked up and down the lovely beach surrounded by beautiful mountains. And yet the telegraph has been broken for months and the ferry doesn’t come any more, and also now everyone is missing.

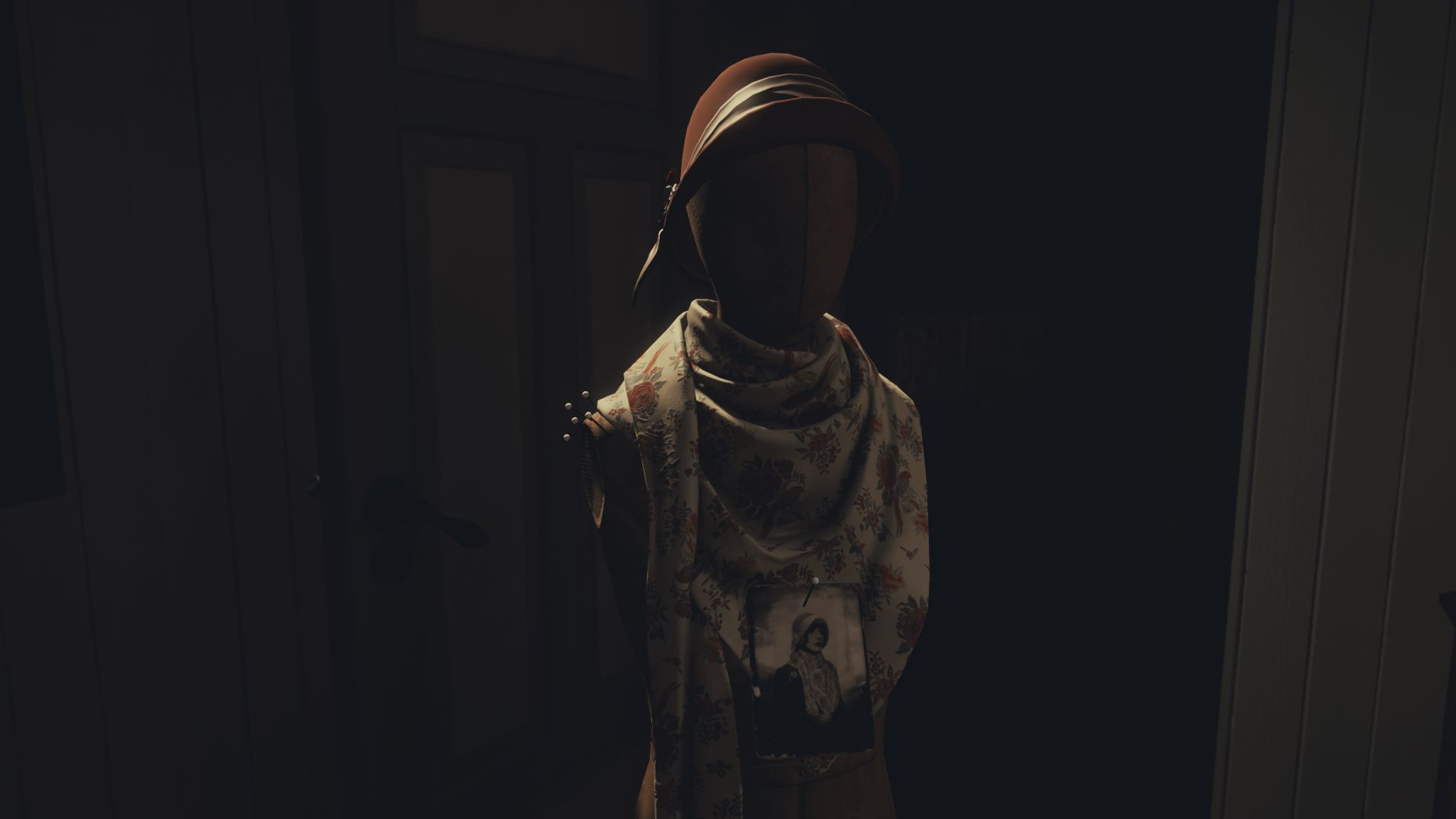

Lissie is remarkably unperturbed by it all. She wakes up early every morning, climbs trees, practises handstands, and chastises Teddy for ever getting scared by, for example, the sudden slam of a door in the wind. She constantly spouts theories on what happened to everyone (maybe they’re invisible, maybe they’re ghosts, maybe they all turned into pebbles) as well as 1920s slang. Tea is “noodle juice”, Teddy is variously “old bean”, “old sport” or “a wet blanket.” It’s sort of like if George from The Famous Five read The Great Gatsby and got super into it, but I really liked Lissie, and the melancholy stuffed shirt that is Teddy.

The relationship between the two is a big tentpole for the game, and it could probably keep the whole tent up by itself. Teddy is constantly worried about breaking the rules, or slippery mud, and behaves in a very grown-up way whilst fighting bouts of nerves and anxiety. Lissie can alternate between being wise and calm or having sudden flares of anger, with a dickhead streak wide enough to drive a Range Rover through.

Teddy will editorialise letters he reads aloud to Lissie, cutting out bits he thinks are boring or she shouldn’t hear; Lissie will shout at him for caring too much about Betty and not enough about anyone else. She will tell him to look at her when she’s talking, and will not continue until you swing around and do so. Their conversations (aside from the opening scene, where the dialogue is the sort of expositional stuff where people say their full names and addresses at each other) are very natural, with throat clearings and slight cross talk, and performed beautifully by Nicholas Boulton and Skye Bennett.

I’ve not yet talked much about the mystery in this “Fjord Noir” because doing so will be a delicate game of not spoiling anything. Draugen reveals itself to you gradually, and though it’s a very small town your progress is gated through the imaginative and honestly pretty funny means of Teddy’s manners. Like the unsexiest kind of vampire, he feels unable to venture anywhere he isn’t invited. Though as the days pass, he becomes more desperate to find traces of Betty, and more at home with the idea that, er, nobody is coming back.

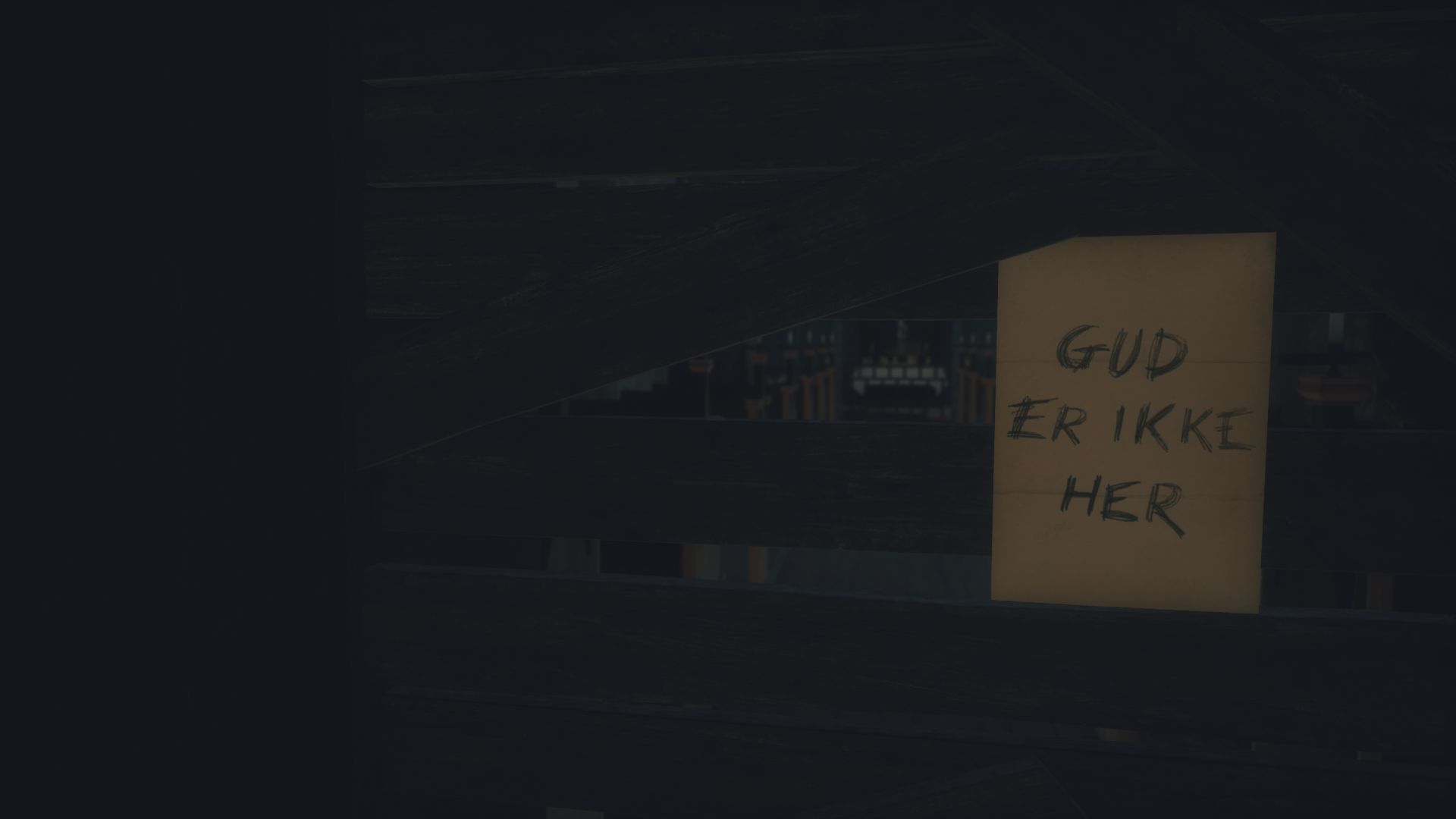

There’s a sense that you have all the time in the world, and the map is small enough that you can approach everything in an unhurried way, though sometimes I did get the spine-tingling feeling that I wanted to run away and find a solid wall to stand up against. You’re never quite sure if something supernatural is going on or not, because Graavik is empty but it feels like it’s stuffed to the creepy gills with ghosts. When you’re upstairs in a house you can hear creaking downstairs. The question, really, is whether you - or any of us - are alone all the time, or none of the time.

Gradually, though, you piece together bits of the Graavik jigsaw, involving two families, a decades-old tragedy, an abandoned mine. A torn photograph here and a half-burned letter there give you an edgy piece, but you never find the full picture, and part of playing as Teddy involves choosing what he thinks about different events or things they find, discussing them with Lissie. This is, as Teddy even remarks in the game, not going to have a neat ending like an Agatha Christie novel. It’s potentially unsatisfying, but Draugen is only a handful of hours long, and I ended up liking the not knowing, because it’s sort of the point that nobody is left who can tell the whole story.

I have some bones to pick with it, but I hesitate to crack them open because the slippery marrow inside is all spoilery. I think I can get away with saying that Draugen does a lot of tropes very well, but it does others in a tired way that garners side eye from me. (If you’re interested and don’t care about the spoilers, there’s already a thoughtful article by Katharine Cross that delves into the subject.)

Teddy and Lissie are still very inviting characters, who obviously have a backstory that is distinct and known to their writers, and are the best reason to play this game. The credits tell me they will return, so that's something to look forward to. Graavik, meanwhile, remains a nice place to visit. But you wouldn’t want to live there.