How one of the finest RPGs ever made thinks about money and magic

Roadwarden's creator on the value of specificity

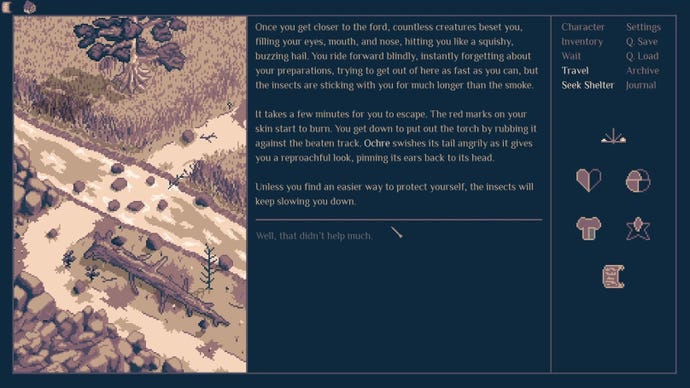

Roadwarden's creator, the Polish writer and designer Aureus of Moral Anxiety Studio, is an enthusiastic and inventive player of table-top games. Many of his ideas for 2022's finest historical fantasy RPG have their twitching, eldritch roots in pen-and-paper sessions with friends. Take questions of money and wealth. Speaking to me over Zoom one rainy October afternoon, Aureus recalls one particular table-top campaign he ran in which, after 10 or so sessions, the player party had sunk into abject poverty. "They reached a collapsed village, [and] they said, 'is there a cart around here?' So I rolled the dice and decided that all right, there is a wagon, that's completely functional with all its wheels and so on. So they just started to walk around and shove on the top of their wagon, whatever of value they could find.

"They had no shame!" Aureus goes on. "Just gathering all the scraps of iron, all the tools, knives, musical instruments, pieces of fabric - anything they could find, they were just taking it all with them on the assumption that whenever they reached a civilised spot, they're just going to sell it all." This was foolhardy behaviour, because all the objects in question were trash with little resale value. "So they at the same time they had more than they could ever need, and they had pretty much nothing. They mainly had a hindrance that was slowing them down - this wagon full of stuff was just difficult to move through the paths."

Then, disaster struck: the covetous adventurers were ambushed by bandits, who made off with their beloved wagon. "I wasn't trying to fuck with them, they just got extremely unlucky," Aureus assures me. But the loss also furnished the group with an objective, which became the basis for an open-ended tale about the perils of unchecked materialism. "For another, like, three or four meetings, the entire campaign was circling around the idea that we want to get our wagon back."

Presiding over it all as games master, Aureus was bemused but also inspired. "They never really needed this wagon," he continues. "It's not like they required a specific amount of coins to spend on something, this one specific item is going to just level us all up so much. Instead, they just had this attachment to the idea that 'this is our key, we can use it to overcome all our difficulties', even though this opulence actually brought more obstacles than it solved. And sessions like that made me constantly think, what's money actually worth to the player? It isn't something that's set in stone. Depending on specific circumstances, how specific characters treat you, how they see you as a player, it's something that can be shaped around a specific story thread."

That emphasis on the specificity of money is one of the things I adore about Roadwarden, and one of the key things I wish the creators of other role-playing games would learn from it, and from the table-top games that have inspired it. Role-playing games are heavily invested in the earning of various forms of material wealth, from coins to crafting commodities, but they seldom invest the act itself with much meaning or drama. It's just a thing you do to make progress: a steady osmotic exchange of playtime for credits you can spend on new tools or equipment, allowing you to gradually burrow through obstacles and reach the endgame. There is often minimal sense that money really exists within the world, that it means anything to the residents. It's just a convenient framework for player progression - certainly, not the basis for a story.

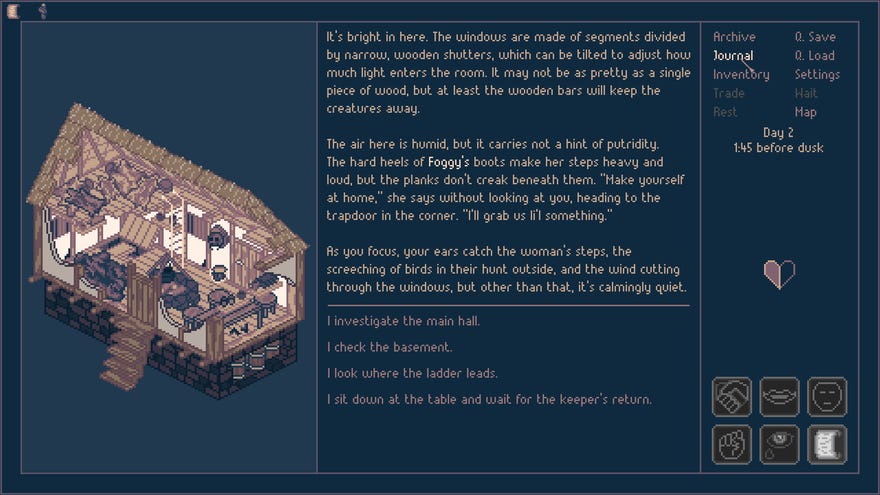

In Roadwarden's medieval wilderness, pretty much every coin you find has a story. It comes from somewhere and someone, whether it plays an explicit role in a quest storyline or not, and it means something different from place to place, and person to person. How people value the game's coins, together with other artefacts that can be traded, depends on a host of factors: what the other party does for a living, who raised them, their religious beliefs and political views, which village they hail from, what social class they fit into and, last but not least, what they think of you. Some people barely acknowledge the world's currency, preferring to barter for food, tools or favours. Others have a pronounced emotional attachment to specific commodities, as with Aureus's table-top gaming group and their lost wagon. There's no generic "merchant" character for whom everything is worth the same.

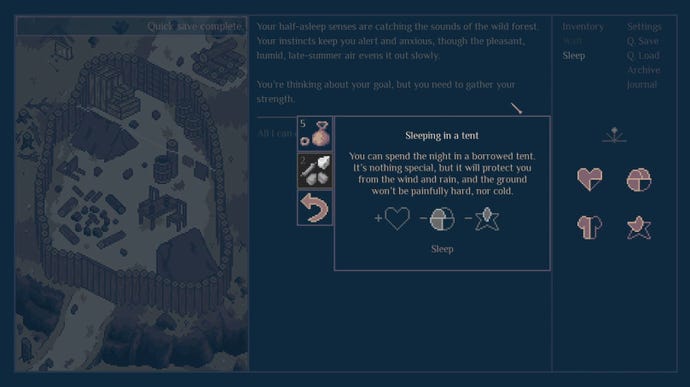

The result is both a more believable, engrossing setting and a setting that works to humanise players who are treated like gold-farming bots by other loot-driven RPGs. It's a world you navigate by paying earnest attention to individual people and communities, rather than grinding away. The absence of any obvious way to earn a livelihood means that every coin in your pocket is the result of a series of careful decisions (and a pinch of good luck). There's also the problem of a time limit - as a newly recruited roadwarden, you only have a few dozen days to explore before winter ends the game, which means that you can't just settle back and mine the setting's few recurring earning opportunities till you're rich enough to make headway.

These are ideas Aureus has been fleshing out since Roadwarden began development in 2018, beginning with the idea that completing a quest wouldn't simply result in a payout. "Very early on, in the first design document, I had this idea that it's not that everyone is going to pay you for completing quests, but rather that completing quests is going to, for example, unlock access to a new shelter," he says. "Or access to shelter that used to cost a coin a night, but now it's free, because people here trust me. And now you have made your mark in this world once again."

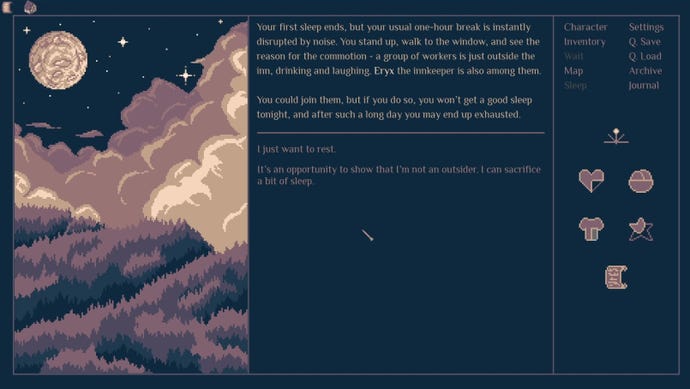

In a wonderful bit of poetry, Roadwarden's sense of the specificity of money also applies to its understanding of magic. Much as the value of coins shifts from village to village, person to person, so the meaning, uses and abuses of sorcery alter as you tramp about the landscape. "For the people who live in this world, magic is fiercely attached to the culture," Aureus notes. "But the culture is not something that's shared by everyone who lives around them.

"For example, some settlements see magic as just another tool that they have at hand," he goes on. "Oh, we have one person that as a kid turned out to have a very great affinity for magic, so she was casting spells that no one in her village knows. We allowed her to break a few pots as she was experimenting. And it turned out that she was actually able to teach a few other kids how to cast spells. Now we use it to, for example, shape the walls around the village - it helps us with mining. But [we didn't send that girl] to the magic university to learn fireballs, lightning bolts and so on. It's just something that helps us with very uninteresting, prosaic activities. It's just another bit of colour that makes that community unique.

"But in another village, magic can be the core part of that community's perspective, of their faith, of their self-identity," he goes on. "For example, having a priest caste that has guided the entire community for generations." One of Roadwarden's more isolated settlements is in thrall to a mage who has exploited the residents' unfamiliarity with sorcery to set himself up as a messenger from god. Elsewhere, a spell is just another tool for doing the chores; you'll meet a woman who's trying to pick up the basics of telekinesis to make life easier as her body ages.

"I don't find anything exciting anymore about fantasy worlds where magic is something like in an isekai anime, where you just have a party and you need a healer, and your healer prays to heal you," Aureus notes. There are, admittedly, traces of the usual class-based RPG magic systems in Roadwarden. Play as a character with sorcerous gifts, as I did during my initial runthrough, and you'll gain a pocketful of scrying stones and a tiny arsenal of offensive and healing spells, which call upon your character's reservoir of pneuma. But the key word is still "specific": the spells are made available to you where it makes sense for the story, and they are choices that alter those stories, rather than being a set of generic abilities.

Again, many of Aureus's ideas about magic spring from his experiences as a table-top player. As captain of the D20s, he seems to have a particular love of unspooling the disturbing implications of supernatural talents. "One of my players currently has a spell that at the start, we just portrayed as amplifying the emotions and feelings other characters in the world have," he says. "And it took only a few sessions before she tried to amplify the bravery of an innkeeper's wife, who was clearly living in a hostile environment, living in the shadow of her husband.

"And the innkeeper's wife became so brave, that yes, she was able to free herself from her husband's influence. But she currently lives without any sort of fear. She wants to follow the party even though she doesn't know how to fight. She believes that they can handle any sort of threat, and with time it became clear that she's pretty much insane, because of what this player did to this character. The same player decides to make it clear that her character doesn't believe she did anything wrong. So instead of staying away from using her powers, she goes all-in - she tries to amplify not just positive emotions, but also the negative ones. She starts to influence animals. She's currently the most murderous character in the entire party, even though she started out very benevolently!"

There are scenarios as outlandish as this in Roadwarden (available on Steam, GOG and Itch) - I won't spoil any more than I already have. But what keeps me thinking about Moral Anxiety's game, a year on, isn't its capacity for Baldur's Gate 3-style eccentricity but its deftness and intimacy, the way it rediscovers and earths concepts other games have elevated into systems, using things as small as coins to express character and setting, while lending a mystique to magic that can be surprisingly lacking in videogames. That delicacy of approach breeds delicacy in turn: it rescues me from the often suffocating role of world-conquering/saving level-up machine bestowed on me by other RPGs, and turns me into a fellow traveller - a friend at the table.