Impressions: Europa Universalis IV

The Least Serene Republic

They say history is written by the victors and they quite often go on to say that Churchill said that, but they don’t appear to have any proof of the latter. I’m here to prove the former wrong as well. This is a Europa Universalis IV tale of betrayal and bellicose bastards, in which the losers have the final word, and that word is an obscenity, bellowed across a field of the dead.

I didn’t choose Venice and nor did Venice choose me, but in many ways I’m glad that I was assigned to the Dogedom of that dogged trade republic. One of the most immediately apparent changes to Europa Universalis IV over its predecessors is an entirely new trading system and Venice is ideally placed to demonstrate those features. That’s the sum total of the pros of being a Venetian in this particular session. It was a learning experience.

The cons will rapidly become apparent as the story unfolds.

Europa Universalis IV was my first experience with a multiplayer session in a Paradox grand strategy game, pre-dating my Ottomanliness in March of the Eagles by one day. March of the Eagles is perfectly suited to multiplayer, with a shorter, focused campaign and predisposition to warmongering and backstabbing. Europa Universalis has always been a more sedate ship of state and I was slightly uncomfortable that my first experience with it would involve other people.

There was no need to worry. Or, rather, there were a thousand reasons to worry, panic, groan, weep, threaten, cajole and grimace, but there was still enough space to become acquainted with some of the changes in between the deceit and lies.

It may be possible to destroy Venice without aid, but I was capably assisted by Fraser Brown, whose account of our downfall has already been chronicled at Destructoid. I think he undersold the blind panic and disarray a little.

The most important thing a leader can have in Europa Universalis is a long-term plan. While the new game has been designed to avoid the terrible troughs into which a nation can fall, allowing for a broader experience and the stronger possibility of recovery from the brink of economic disaster, as soon as advancement begins, the world begins to take shape. Portugal, played by Paul Dean of Shut Up & Sit Down in our game, is geographically suited to exploration, and that’s what Paul concentrated on, mostly avoiding the quagmire of war that overcame the Old World while he sought new lands to conquer.

Venice could follow that route but, as in history so in the game, the republic is suited to a mercantile role, drawing all the wealth of Europe through its ports and using that currency as both an ATM for its mercenary armies and an armour against attack. Screw Venice and you screw yourself, provided enough of the trade that makes Europe turn is diverted through its counting houses.

It’ll take more than a couple of hours with the game to appreciate the full extent of the changes to the trade system, but it is the most obviously altered part of the game. Merchants can now be assigned to trade posts, at which point they act as magnets of a sort, or railroad signals, pushing wealth toward the final destination on that route. Venice is ideally situated because almost anything of worth that passes between East and West can be sucked into its Lagoon and converted into riches.

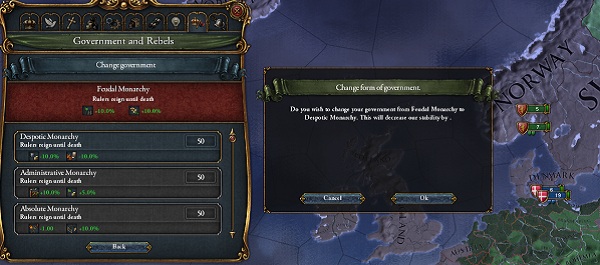

It’s important to keep control of the Aegean isles so as not to be cut off from the wider world, however, and pirates and enemy navies also occasionally become attracted to the Venetian shores, looking for trouble. What, then, would be our long-term plan? Bolster trade by building a navy and expand our holdings on terra firma. The biggest problem and the cause of the majority of our problems is that those two goals weren’t related to one another. We decided to kick Lombardiass because the new ‘goal’ system promised us shiny things if we did.

We could have ignored it, but the entire reason that Venice exists is to host film festivals, murder Donald Sutherland and accrue shiny things. Also to subside romantically (and, when the waste is lapping against the doorsteps, malodorously).

So we declared war on Lombardy and about a month later Venice was sunk. In about five minutes of play-time, we had achieved what centuries of being an entire city propped up on wooden struts in a furiously hungry lagoon couldn’t.

Blame it on the panic of running in real-time in a multiplayer environment without the convenience of pausing every ten seconds. Lombardy had allies and rather than popping a sword into the hands of our gold-laden merchants and sending them to war, we had recruited mercenaries. Lots of them. This meant that even though our trade network was as intricate as Ariadne’s thread, we were spending faster than the ships came in. To make matters worse, the mercenaries were losing, dying in their droves. We figured they were probably Lombardians anyway, so in a way we were winning. Certainly not the moral high ground, but at least no Venetians were dead. Yet.

When every single province to our West declared war, give or take, we had no response. The Venetian people did. They formed rebel bands and set fire to things, protesting the massive loans we’d taken out, the fact that all their hard merchanting was reaping no benefits and the preponderance of angry Milanese folk who were laying siege to their homes. To be fair to our fair citizens, they had a point. They had several points, mostly on the end of the pitchforks that they were bashing against the doors of our Doge-house.

Enter Austria. Joe Robinson has written for RPS before and I considered him to be a man of honour. Turns out he’s a total war-bastard. Offering assistance in the form of gigantic enemies, he drove off the rebels and freed our people from the Lombardian threat. At this point, our holdings in Crete rebelled, demanding independence. We dealt with some rebels by meeting their demands rather than fighting them but we would not surrender Crete – it was the gateway to our trade routes and without it we lost our teller’s window on the sea.

Austria could not be moved to liberate Crete as well so we gathered more mercenaries, took out more loans, watched our coffers empty, wondered briefly what coffers were, and then converted the Grand Canal into a repository for our tears. One province of Lombardy was ours, at least, but the Austrians were sort of hanging about, en masse, almost as if they had killed all the rebels simply to conquer us anew. But our friendship was built on bonds of trust, so we didn’t think too hard on that.

I'm going to talk about Lollards now. I hope you're not a Lollard because, good grief, I can't stand them. As far as I understand it, here's what they are: Lollards are monsters that sprout in the dark of night, like mushrooms in a cellar, and lay waste to all that lies before them. They cannot be bargained with, they can't be reasoned with. They don’t feel pity, or remorse, or fear, and they absolutely will not stop, ever, until Venice has fallen. The excitement of being attacked by actual heretics with demonic banners was soon replaced by despair as the horrible creatures multiplied faster than rabbits in a lazy simile.

As Crete burned and the Lollards just sort of lolled about the place, Joe’s Austria struck. He explained later, over a beer, that he had been given the mission of ‘liberating’ one of our provinces. He claimed our people were oppressed and that they’d be happier under his rule. Looking back, he was probably right, but at the time I just hoped he’d choke on his beer, or at least suffer from a moderately terrible hangover.

The canals were clogged with corpses. The coffers were full of blood. The Republic was repellent, a ruptured colostomy bag of feeble ambition and stinking greed. Multiplayer is harsh, or at least the players can be, even if we didn’t see much of the rest of them. It was a fantastically enjoyable downfall but it is difficult to appreciate everything that has changed without the benefit of time alone with the game.

Trade is more involving but the system doesn’t seem too difficult to understand and small touches such as the missions and ability to communicate with rebels, understanding their unique demands and acceding to them if suitable, lend events a greater immediate sense of personality. Lessons have clearly been taken from Crusader Kings II, most notably in the representation of information. Overload is avoided, but there does seem to be less impact from hidden figures, with data collated in sensible places.

I’d need a few days alone with the single player to see how well the interface is tuned and whether there are any problems apparent in the late game. Or anywhere else really. With a game so broad and deep, some issues won’t necessarily become apparent in the first two hundred hours of play, but what I’ve seen is very solid, not quite a hybrid of CK II and earlier EU games, but something close to that. Importantly, there look to be as many choices in the way that a death throe is enacted as there are in the way that an empire is constructed, and for the whole grand scope to work, that’s absolutely essential.

Europa Universalis IV is out in Q3 2013.