Premature Evaluation: Layers of Fear

Gone Mad

Each week Marsh Davies lets fly at the blank canvas of Early Access and either returns with a masterpiece or ends up rocking back and forth in a corner eating Unity Asset Store crayons. This week he’s played Layers of Fear, a linear boo-scare walk-em-up set in the reassembling spooOOooky house of a maaAAaad painter.

I’m not sure a household needs more than one reproduction of The Abduction of Ganymede. It’s a fine work, sure, but I don’t want to be staring at a pissing toddler’s dangling bum while I’m having dinner, let alone every time I turn a corner in my home. But then, I’m not really sure of a lot of the other decorative choices that my character appears to have made here - the cupboard of black phlegm, the infinite library, the hell mirror, the Erik Satie levitation cellar, the room of bad chairs. Not even Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen would go so far as to daub “ABANDON HOPE WHILE YOU STILL CAN” above a doorway. It doesn’t even make sense, Laurence!

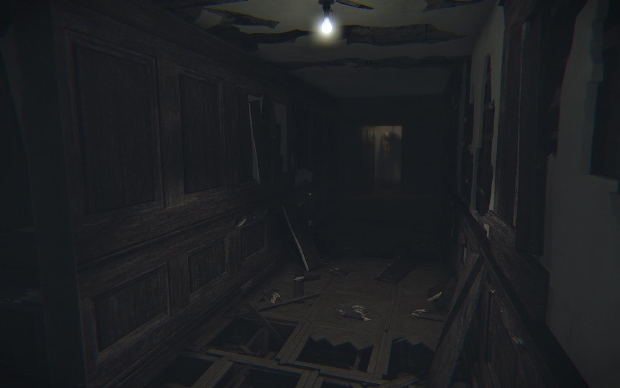

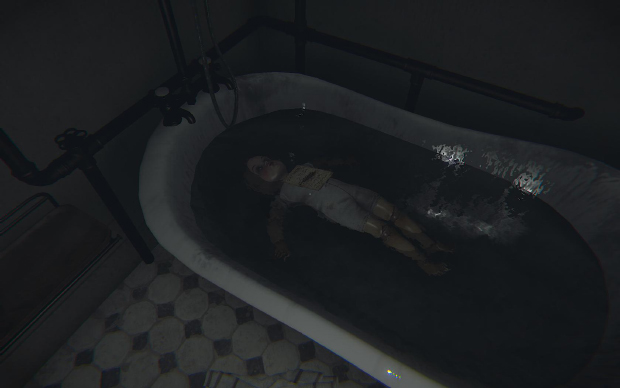

What initially promises to be a freeform exploration of the protagonist’s quaintly demented home turns into a linear ghost train pretty quickly, reassembling the house to provide a nightmare sequence of nicely furnished but spatially impossible rooms. Many contain things designed to assault you unexpectedly - or, failing that, at least loudly and suddenly. Turn around and the corridor behind you will have changed into an entirely different one, sometimes slathered with horrible black ichor, sometimes with a creepy doll in it, doing that wibbly-wobbly-head thing that creepy dolls and paranormal entities have done since Jacob’s Ladder came out. Console gamers will also remember the yucky lady from PT, who turns up here to do pretty much exactly what she does in PT, beat for beat.

When it avoids cliche, however, the game’s tricks and choices are quite effective. Paintings seem to melt and smear as you look at them, and then the entire room along with it. The environments are attentively constructed, seeded with the odd prop that you can pick up and admire in lustrous hi-poly detail - albeit to no particular end. And if it doesn’t quite match the alarming photo-realism of PT, then it achieves enough fidelity to make the disruption of physical space unusually powerful. The various visual distortions and hallucinations you suffer are appropriately disorienting, but it’s the game’s reassembling geometry that steals the show, luring you into rooms which turn out to have no exit; turn around and the one you came through is gone.

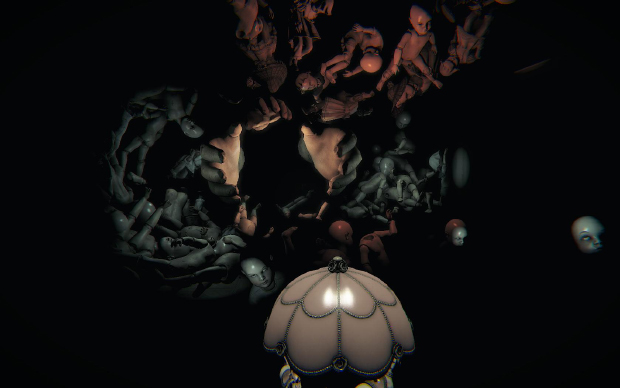

It has to let you out eventually though, and this knowledge becomes something of a problem. I am easily startled and rarely scared by these sorts of games - and yet, not that far into the 90 minute running-time of the Early Access build, I was no longer being startled either. The rhythm of the game becomes too regular: go into room, wait for things to go bang or woo, leave room by the one available door (sometimes the one you came in, though it may now lead somewhere else). There’s nothing wrong with this set-up until it becomes the only set-up you’ve got, and though Layers of Fear does occasionally break up the pace with a trivial puzzle, the reliable frequency of its shock moments prevents them from being exactly that. Yes, yes, giant bleeding baby face, I know you’re going to be there when I turn round. And there goes another mirror. Time for the lights to go out.

The game isn’t always good at directing your gaze to even witness these things: on more than a couple of occasions, a loud bang and dramatic sting of music signalled that I had missed the event entirely while examining a particularly nice chair asset, or rummaging around in drawers (all of which are operable with a pleasingly tactile analogue mouse-movement). Oops! Sorry, ghosts.

But in spite of this, when it’s not knocking off PT, it comes up with a few horrors that are suitably spectacular to be worth the price of admission. Unfortunately, I can hardly say what they are without spoiling them - which is simultaneously a criticism of the game’s other, more derivative efforts, which come pre-spoiled by all the films and games you’ve seen which had them in too. In general, I am confused by the horror genre’s fondness for regurgitating cliche. I guess there’s some associative fear-response to horror film imagery you’ve encountered before, and I guess, too, that a manky thing that’s trying to kill you is fundamentally unsettling regardless of how many times that threat is presented.

But, even so, the most effective horror hinges on its unfamiliarity: Sadako and the xenomorph are terrifying precisely because they are unknown both in their capabilities and their intent. Too many films have since thought Sadako was scary because she has terrible posture and needs a shower - as though by nudging you in the ribs and saying, “Hey! Remember when you saw that other movie that was scary?” you will instantly buy into their superficial reproduction. It’s to mistake mere imagery, mere reference for the richness of imagination required to concoct something truly unknown.

Needless to say, Layers of Fear is at its best when coming at horror from its relatively unusual perspective: that of the artist. Though rarely seen, the protagonist’s own paintings are enjoyably ghastly, and the game punctuates your descent into lunacy with repeated modifications to a single canvas, slowly conjuring an image that lies almost exactly between Francis Bacon and Clive Barker. I can’t really lay out any more of the plot without evaporating some of its intrigue, but I can say that the delivery of it leaves a bit to be desired - voiceover recollections are hammy and the writing is clumsy with modern colloquialisms, contradicting what appears to be an ambiguous period setting. (I wonder if younger players will understand how to work a dial-operated phone.) It’s definitely from the Thematically On-The-Nose Blood Graffiti school of environmental storytelling.

Some visual bugs undermine a few of its hallucinatory reveals, and, being a game you’re likely only going to enjoy once, I’m not sure I’d recommend playing it before the experience is fully polished. A note pinned to a door uses the phrase “if you care so lunch” - all the more peculiar an error given that it appears to be handwritten, rather than a typo. There are lots of other minor mistakes besides, but what I really want from the remaining time in early access is not precise spelling as much as a different pace. The game’s less linear opening, and the objects you can pick up and inspect, suggest the possibility of a more sober structure, perhaps with more involved puzzling or a liberated sense of spatial exploration, which would amp up the contrast of the game’s attempts at alarm. At the moment, the relentless pummelling you receive only goes to prove that, no matter the game’s visual imagination, players can get used to anything - even something as truly horrifying as Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen’s interior design.

Layers of Fear is available from Steam for £6. I played the version with the Build ID 750039 on 31/08/2015.