Of London And The Sunless Sea: Failbetter Interview

London falling, and I wanna shout

"Have you ever been to Córdoba?" It's not the sort of question an interviewee normally asks me but this isn't a normal interview. I'd like to say that I spoke to Paul Arendt and Alexis Kennedy of Failbetter games in a corroded wine cellar by gaslight, but that would be a lie. The creators of Fallen London work in Digital Enterprise Greenwich, overlooking the Thames from on high rather than sifting through its waters in search of stories to tell. I've had a long and fulfilling relationship with Fallen London, and Sunless Sea looks like a marvellous mixture of Elite, roguelike and top notch storytelling, so I was hoping for a fulfilling conversation.

A couple of hours later, we'd talked about everything from Dark Souls to Dickens, and the world felt like a more fascinating place. These are two of the most interesting minds making games and whether you've played Fallen London or not, you would do well to consume their thoughts.

RPS: Fallen London was a revelation when I first started playing it, partly because it’s a free-to-play browser game that I found myself happy to participate in, and partly because it has writing that I enjoy, not just in a narrative sense but in a literary sense. That’s unusual. It’s an unusual game. Where did it all start?

Kennedy: Back in 2009, I was a web developer and I wanted to make a text game rather than a video game per se.

Arendt: And I was a journalist rather than an artist at that point.

Kennedy: The new thing at that time was social games and my plan, almost explicitly, was this. Step one – Mafia Wars has several million players and Mafia Wars is shit. Step two – let’s make a game that isn’t shit. Step three – question mark. Step four – profit. Unfortunately, it turns out that what you need to do is not just put an interesting story in a game but mess about with spammy, viral contacts. Let people really get into the economic details of your free-to-play model. We always had this thing where we wanted to be viral but to be gentle about it.

RPS: You are very polite whenever you contact people through the game.

Kennedy: We were very polite but people didn’t know we were going to be polite until they’d actually given us their contact details. It’s all well and good saying ‘you can trust us, we’re lovely’, but people don’t trust that and rightly so. Anytime we got any press, the third comment would be, ‘Oh, it’s one of those Twitter games’. So we didn’t get many people signing up and we didn’t have the advantage of spamming the hell out of the people who DID sign up, so we had the worst of both worlds. Now we do no viral marketing at all, or sharing at least. The only options for that are the standard Facebook and Reddit links.

Arendt: We just weren’t comfortable with it as much as anything else. When we relaunched as Fallen London, we decided that we’re not a social game, we’re a story game. The line we had at the time, about social gaming, was ‘what’s the point in being Darth Vader if you can’t use your evil Force powers’. We might as well be on the side of the angels because it’s what we want anyway. I’ve felt a lot better since then.

Kennedy: (laughs) Me too!

RPS: Free-to-play is a warning sign for a lot of people still. It is for me. To make it work as well as it does in Fallen London has surely been a case of making the content fit the model. There’s an element of grind but the sentences feel like a reward, and a much stronger one than a +1 belt of encumbrance.

Kennedy: That’s the effect we’re going for.

RPS: It’s refreshing to be rewarded with words for a change. Paul – does your journalistic background play into Failbetter? What did you do?

Arendt: Well, it was back in the day. Film reviews and stuff at The Guardian. I used to draw in my spare time. Alex rang me up one day and said I need ten icons for this little game I’m doing. Ten became two hundred and then we decided to create a business!

Kennedy: Paul wanted to do it for fun at first but I said I wanted to pay him because I wanted this to be a business. He found out what I was doing and said just to give him a percentage instead and I can remember thinking ‘OK, I will, but you have to understand that it’s likely that we’ll never make any money out of this.’ And we haven’t made a lot of money. But we’re still here!

RPS: Did StoryNexus come first, as the basis for Echo Bazaar?

Kennedy: Yes, although because Echo Bazaar was two or three years old by the time we launched StoryNexus, we built that properly afterwards.

Arendt: It was originally called Jonathan. That was its working name for ages.

Kennedy: Then Prisoner’s Honey. Then StoryNexus.

Arendt: The most boring name we could think of. We were trying to think of cool names and ended up with that.

RPS: Failbetter is a direct Beckett reference though, right?

Arendt: Oh yeah.

RPS: It reassured me that you were serious about words as soon as I saw it.

Arendt: It’s gaming as well though, which is why it works. It’s very Dark Souls if nothing else.

RPS: Dark Souls is the ultimate Beckettian game perhaps.

Kennedy: I was talking about calling it Buzzkill Games but we decided, no…Our inspiration was to build interesting worlds, like EVE or Warcraft, with all these elaborate fucking backstories, and you’re kind of limited to how much you explore those actual stories because you’re driving spaceships or hitting stuff. But still, after ten years live, there’s a lot of fascinating stuff there. But there’s no way, especially with my children, to devote myself to raid level content, or to EVE. I loved the idea of something that would allow people to be immersed but would only take a few minutes of their time every day, in order to get a sense of something sprawling and immersive.

RPS: I find many apparently immersive worlds troubling – and I’m picking a recent example, not the worst example by a longshot – they often have the ‘explore down the barrel of a gun’ mentality that Bioshock Infinite falls back on very quickly. It’s an interesting place but I don’t find the means of interacting with the place particularly interesting.

Kennedy: Agreed. I like to keep up to date with developments in narrative and at the point Infinite came out, I bought it on the basis of two 10/10 reviews, and then I got the sense that after people were no longer wowed by it, they had some reservations.

RPS: I think it’s an interesting example to use in relation to Fallen London because Infinite doesn’t work for me as a game about the city – perhaps it works better as a game about games about shooting people. Dishonored’s Dunwall worked as a city. IF you look out of the window here, you can see the Thames, which is a bit of Dunwall. How much of your game is your London?

Kennedy: First of all, I’d say that Infinite works as a city in the first fifteen minutes. At that point you’re a tourist, observing people, learning how things work in this strange environment.

RPS: Being a tourist is one of my favourite things to do in a game.

Kennedy: When we say ‘exploration’, we mean two slightly different things. We mean looking around a corner and finding secrets, ammo and extra coins. And then there’s the sense of tourism, of wanting to take a holiday inside the screen and to poke around. I have a very ambivalent relationship with London. I moved here under protest and I think that probably expresses itself in Fallen London. Paul actually moved OUT of London.

Arendt: I did. It’s probably the opposite path.

Kennedy: I think the people who write and build the most interesting things about a city are those who have an emotional reaction to it that isn’t necessarily entirely positive. I always think Peter Ackroyd probably really hates parts of London.

Arendt: It has extraordinary texture. It’s an entire society in a small area and that it exists is incredible. It’s so grimy, and a gift for artists.

RPS: It’s a great shame that everybody who visits isn’t forced to spend an entire day just walking. It’s a layered city, a sort of palimpsest of urban history. Almost everything that has been co-exists, really badly at times. Think of St. Pauls, hemmed in by offices and cafes.

Kennedy: Have you ever been to Córdoba?

RPS: No.

Kennedy: Do you know the Cathedral-Mosque there?

RPS: Yes. By reputation.

Kennedy: So, they put the cathedral through the roof. Apparently the Hapsburg Emperor at the time told them that they’d destroyed something unique to build something commonplace, and I think he was exactly wrong. They built something unique. And that’s a really good type for the kind of city experience you’re talking about. St Paul’s Square has these contrasts that are forced to exist in a city and they’re so uneasy, they’d have no reason to exist anywhere else. They’re an offshoot of the sustaining pressure of people, histories and cultures having to exist side by side.

RPS: Fallen London, despite and perhaps because of its oddities, feels very British. It’s a very boring thing to say, I know, but it IS very Dickensian. I think Dickens is the great writer of London, still…

Arendt: He’s a huge influence. He’s all over it.

Kennedy: How do you get the sense of Dickens, the smell, the aesthetic, without just mimicking his style? He’s so expansive and that’s precisely what we can’t do, face players with walls of text, so we have to capture something of him without using his methods.

Arendt: A lot of these guys are in the game, disguised, in some form or other. Huffam is Dickens.

RPS: Who else is lurking in there?

Kennedy: Freud.

Arendt: Ah, I’d forgotten about that. (laughs). Doctor Schlomo. Yes, it just tends to be their weird middle name.

Kennedy: Holman Hunt turns up in one of the early ambitions. We have a reference to Wilde, although I can’t remember exactly where that is.

Arendt: We’re a bit more sniffy about using fictional characters because there’s always a danger that we’ll turn into the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. But the historical stuff is all part of the fun.

RPS: Do you bring in anything more modern? Or do the references have to be period-specific. I quite like the idea of bumping into a Will Self analogue.

Kennedy: I was really a fascist about this…

Arendt: (laughs) You certainly were.

Kennedy: You play an MMO and every fifth quest title is a rip-off of a Who episode or a Mario gag. I absolutely wanted to avoid that although I was quite rude about Batman in one joke quite early on. But everytime I saw a modern pop culture reference inserted by somebody, I’d stamp on it. Somebody managed to get a Star Wars joke in one time.

Arendt: Yeah. There was trouble about that. But you did do a Bladerunner reference!

Kennedy: (laughs) Yes. I know. It was about a city! I’ve relaxed on that though. We’ve got an extremely strong sense of what Fallen London is now, and so many words to shore it up, that it can stand a little bit of erosion through these references. But we had to establish that specific sense of place beforehand.

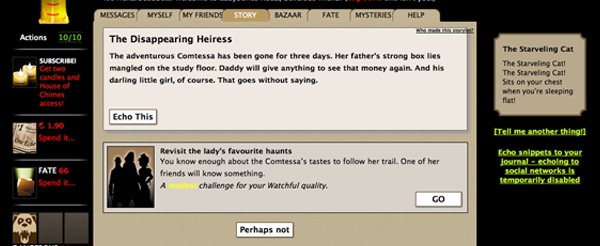

RPS: As allusive as it is, it does have a language that is very much its own. I’m consistently impressed, as a somewhat verbose writer, that you manage to achieve that in such small bursts of text. How much is cut and dropped? Do you have it to a fine art, this short-form expression, or do you write longer and chop away?

Kennedy: These days I’m the only content writer on Fallen London. We were up to four writers at one point but we couldn’t sustain the company at that size and the core content was built. I’ll be added to that, probably for years. I make a point of writing directly into the Story Nexus CMS (content management system). I actually use a slightly less funky version of the main CMS. Writing directly into that constrains me to the system. If I’m writing offline I’ll make notes but I will generally build the structure and then add the text to the structure. I rarely start with the text. It’s so important to provide relevance to the text.

Arendt: There was something we did at the very beginning, which was to import some journalistic practices into games writing, which is something that I don’t think is widely done.

RPS: There’s still not a huge amount of thought in most games writing at all, let alone journalistic practices.

Arendt: (laughs) We had fairly strict back and forth on how to create the best writing we could in the most efficient way.

Kennedy: I can knock out some content in the morning and have it out by lunchtime. Most games just can’t do that. It’s not possible to get content live that quickly. In an MMO, you can’t have a designer think of something in the morning and have it implemented in a couple of weeks even. Of course, that’s because they’re much more substantial and immersive productions. We work almost as if we’re going to press rather than putting things into a game.

RPS: The actual implementation of content and the editing of the words is something that most people probably never think about. Fitting the fiction to the form. You’re probably aware of Twine? I know very good writers who struggle to make their work fit that form. There’s art and craft in fitting within those spaces. Do you call your work interactive fiction?

Kennedy: For lack of a better term, yes. No, fuck it, not ‘for lack of a better term’. We’re loud and proud, we’re interactive fiction. The term often means parser-based text input. Story Nexus was a nominee for an XYZZY award this year and one of the people who read about it said, ‘can we call this interactive fiction? It has too many numbers in it!’ But it is fiction and it is interactive. The term has long since gone past the parser fiction. A lot of the people who originally worked in the form are building very fine work that doesn’t fit the original sense of IF. The term has moved on.

RPS: Do you enjoy playing with the form? You said you don’t like to make too many references to pop culture, but do you enjoy making any sort of gaming meta-commentary?

Kennedy: Occasionally. Have you played the Nadir content?

RPS: No.

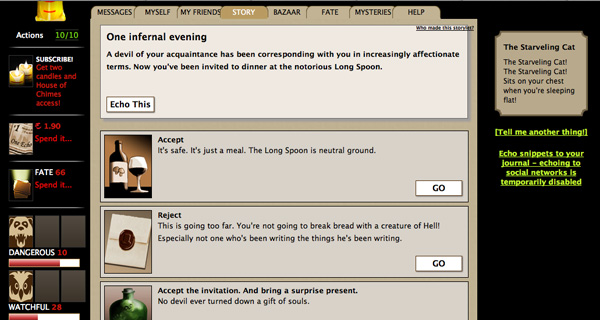

Kennedy: It’s some of the more dream-like, impressionistic content. The Nadir is the place under the Forgotten Quarter and when you go there you draw a load of content cards and then get expelled. There’s a card in there in which you overhear a conversation – somebody is saying that there’s only one choice to make and that choice is to go onward. But, the speaker asks, is that even a choice at all? And there’s only one choice on the card and that is to say, ‘yes! It is a choice.’

But there’s an obscure piece of content that unlocks another option, which is to say, ‘no, that’s not a choice, it’s something else’. That explores some of the ideas about choices in an interactive medium and there are other examples. There are references to other bits of interactive fiction.

Arendt: There’s a grue reference (laughs).

RPS: There’s always a grue reference in these things. I think it’s in the rules.

Kennedy: It was Christmas! We were being silly.

RPS: That is the correct way to be.

Kennedy: We do play with the idea of consent, and of choice and consequence. We’ve done experiments with different narrative voices, going into the past tense. There’s some Easter Egg type stuff that goes into first-person. A lot of conventions in games and interactive fictions are there for good reasons, and a lot of them are there for completely arbitrary reasons. Hitpoints and armour class for example. Wizards not wearing armour. Dungeons that are holes in the ground that you go to that are full of gold.

The reason that we have those is that back in 1976, a bunch of wargamers in America decided that’s how things worked in one particular instance, and everything since then has tended to take on those traits. It’s entirely possible that things could have developed in a completely different direction. Our type of adventure could be the forbidden forest rather than the dungeon, or that your village is under attack and you defend it through generations, building a saga, which is how a lot of myths and folklore tales work.

I suspect that most developments would be combat-focused, for the same reasons that action movies are so popular. But a lot of the traditions for interactive fiction – second-person being used for example – came out of Choose Your Own Adventure books and Colossal Cave, which were both experiments.

RPS: Nobody who creates these things knows that they’re making a long-lasting foundation. Or if they do, it’s possible it doesn’t work as well as the experiment.

Kennedy: One of the lessons from history is that when people have tried to set an example, saying this is how stories should or will be told, it’s almost always of its time rather than for the future.

RPS: Often a footnote that tells us where those ideas were at that time rather than where they would develop in the future. Briefly going back to the non-Failbetter ‘fail better’ game, Dark Souls, one of the things that fascinates me about that game is that it contains an incredible world, but it’s so strange to explore. It has a bizarre verticality – there’s a castle, some ruins, a city, and then a forest beneath all of that, with a lake at the bottom of the world.

Apparently, one of the reasons that world is so strange, according to Miyazaki, is that he had interpreted Western fantasy, as a youth, through the lens of Japanese translations, which made the worlds stranger. It’s not quite as simple as putting Lord of the Rings through Babelfish and discovering Dark Souls at the other side, but there’s a very real element of confusion and an enjoyment of that confusion.

Arendt: It almost feels Lynchian to me. Like it has a direct pipe into my dreams.

RPS: There’s a structural sense to it but it’s not an architecture that I recognise.

Arendt: It does take you back to when you first started playing games.

RPS: Miyamato has said that Zelda was partly inspired by exploring as a child and always feeling that you’d find something magical. Dark Souls feels like what would have happened if he’d been afraid of what he’d find instead of excited. It’s an alternate history of what the fantasy RPG can be, and that, more than the difficulty, is why it’s so fascinating.

Arendt: And to an extent, it’s because it’s a personal game. That’s one of the advantages we have, as a small company. What we create doesn’t have to go through fifteen different iterations and earn approval from different groups of people.

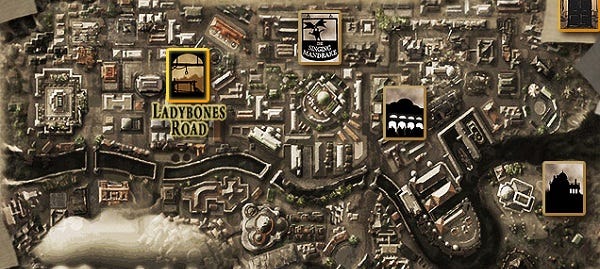

Kennedy: One of the things about Dark Souls - and this is something that both you and Chris, one of our writers, have picked up on – is that you always have a sense of the world around you. You can see other places in the distance, which makes you a part of the location. It’s a distinctive element of fantasy fiction – the map at the beginning of the book. One of the key things about these worlds in games and books is that the reader or player wants to see more of them. Sometimes it’s as simple as showing a map, whether it’s the slow unveiling of Civilization or the hotspots that fill up the map in Baldur’s Gate, there’s a sense of a world that you’re slowly seeing more parts of, building a relationship with it.

It’s one of the reasons that our next project, which is an honest-to-goodness videogame, has a user interface that is an actual map. You are exploring a map. One of the things that grabs peoples’ attention with Fallen London is that you do have that map at the beginning as well – here is London and you can unlock it a bit at a time.

Tomorrow, the conversation continues, with plenty of details about the Elite/roguelike mash-up that is Sunless Sea and thoughts on how to make free-to-play work for both the developer and the player. We also continue our whistlestop tour of gaming history, world-building and London's literature, before eventually deciding that the vast majority of stories are rubbish.