Palworld's skin-deep Pokémon parody is part of a bigger horror story

The law is an ass

Dig back far enough into the history of any word and you'll find something sinister. Take "cute". Nowadays it means pretty, lovable or charming, albeit perhaps with an undertone of mistrust or contempt, as in the phrase "that's a cute observation, Edwin". But the word originally evolved from "acute", which very broadly means sharp or intense. "Acute" was once a Middle English word for a short-lived fever - it's related to "ague", a word you've likely come across in a medieval fantasy RPG somewhere, which refers to fits of sweating and shivering. The word "cute", then, is secretly diseased, and so, perhaps, is the experience of cuteness. There's a psychological phenomenon called "cute aggression" which refers to the desire to physically envelop, dominate and even abuse the thing you find cute - "I just want to squeeze you till you pop".

Videogames know all about these queasy, mingled ideas of "cuteness", especially when it comes to portrayals of non-human animals. Among the contradictions that games somehow thrive around is the insistence on representing animals as both things to adore and things to exploit - a tendency epitomised by the mania for petting mechanics in games where players otherwise spend their days flensing the fluffy critters for crafting materials and XP.

Some games put this act of having-it-both-ways under scrutiny. Pupperazzi, for example, pokes fun at how pictures of pets have become a social media currency - indeed, a literal cryptocoinage, building on centuries of "monetising" animals as dynastic symbols and religious icons. We Are The Caretakers looks at animal companions in party-based RPGs through the lens of decolonisation. And then there's Palworld, which is essentially Pokémon portrayed as what Pokémon really is, for all its attempts to tell a kinder story about itself - a game of virtual cockfighting.

Nobody in their right mind would call Palworld a complex parody of Pokémon, or a clever satire of games that both cosy up to and commodify the wildlife. The satire begins and ends with turning the above cute/exploitable disconnect into an openly macabre sales pitch. Rather than emphasising the emotional bond and sense of respect between animal and trainer, as Pokémon typically does, the Steam page boasts of the chance to not only capture, but slaughter the Pals or work them all to death on your factory lines.

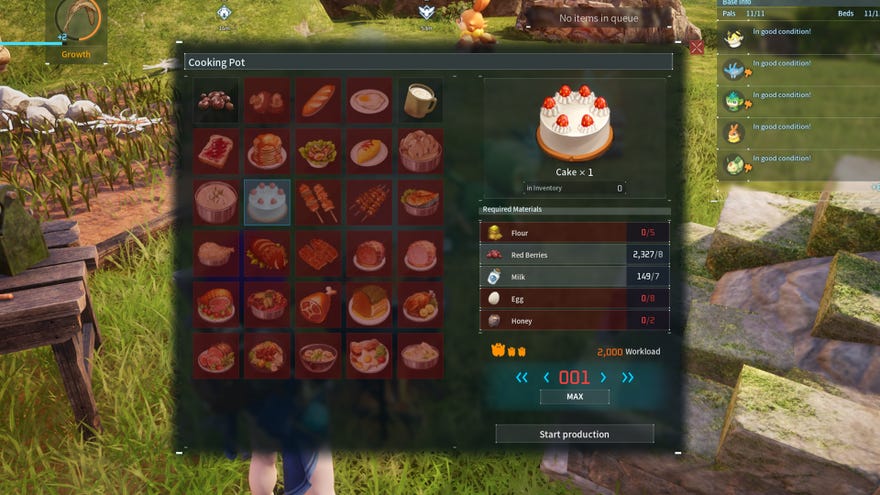

It's not so much a parody as a vindictive pastiche of Pokémon and various other games, one that plays up the "cute aggression" aspect of Pokémon by requiring you to personally clobber the beasties you're hunting, but which is otherwise a perfectly routine survival game defined by base-building and upgrades, with the monsters doing double-duty as labourers. I like Palworld's willingness to belittle Nintendo, one of gaming's greatest sacred cows. But the satire is all edge, without much wind-up or follow-through: cheekily turning the "pet" button into the "butcher" button when you're holding a cleaver, for example. Or censoring the butchering process when there is nothing much to censor beyond some bloodless writhing-around, which makes the whole thing feel like a pisstake of the player for being squeamish.

You don't really need to play Palworld to grasp all this - again, it's right there in the bullet points and gifs on the Steam page. Still, I'm kind of hypnotised by Palworld, and not just because it's not all that dreadful as a work of "pure" mechanics. The clashes over whether it actively infringes on Pokemon's copyright are an inadvertent satire of clashes over whether animals can be "copyrighted" in general.

Human beings have been trying to portray other species as their "intellectual property" for decades, depending on how you write the history of "intellectual property". Selective breeding in modern industrial agriculture is to large degree about stopping other people borrowing your homework. Take US chicken-farming in the early 20th century. Corporate historian Glenn E. Bugos has a paper on the subject that discusses hybridisation, the process of pairing "pure" breeds of chicken to create unique sub-breeds with desirable traits, such as faster growth.

Where purebred chicken species can be "stolen", simply by acquiring their eggs and breeding the chicks, you can't do this with hybrids without re-rolling the DNA dice, and producing unexpected new varieties of chicken. Hybrid chicks "would reflect an almost random expression of all traits," Bugos points out. "From the farmers' perspective, the pedigrees would genetically self-destruct. Bred directly into the hybrid chick was the means to keep them from being illegally reproduced."

These older means of "breeding copyright into" farm animals now go hand-in-glove with genetic engineering technologies, which allow companies to optimise creatures from the cells upwards to suit their goals. Animals brought into the world this way can be portrayed as pieces of futuristic technology, subject to the associated legal protections when they enter the marketplace. There have been attempts to patent genetically engineered breeds of salmon, pigs, beagles, mice, sheep and oysters. Many such patent applications have failed, because views on the legality and ethicality of treating lifeforms like logo designs vary wildly by culture or country. But legal scholar Lena Anna Kuklińska argues nonetheless that, as of 2021, "patenting living organisms is an accepted practice".

I find all this fucking diabolical. But I do love a good horror story, and I'm fascinated by how Pokémon and Palworld are accidentally playing out the question of whether a creature can be copyrighted - both in terms of the debate about whether Pals are actually "stolen" Pokémon designs, and in the shared player objective of pairing monster breeds to spawn the definitive, all-purpose subspecies. Pal breeding is both Palworld's obvious endgame and an ironic counterpoint to claims that it is a copyright-infringing clone of Pokémon. Dip into the game's Steam forums right now, and you'll find threads full of players discussing methods for splicing together the perfect Anubis, even as arguments drag on about whether Anubis is actually Lucario with the serial numbers filed off.

It's a budding cottage industry, the kind most sandbox survival games can only dream of. There's even the makings of a black market, akin to the brutal underground trade in exotic pets: actual Pal poaching between players (as distinguished from representations of poachers in the world) is already a significant issue, as Pocketpair have just indicated by attempting to patch it out. You can expect the dirty tactics to intensify when the developers introduce arena multiplayer to the game and give players a proper competitive incentive to cultivate the most formidable breed of Pal.

Pokémon first released in 1996, almost 30 years ago. Palworld is but a couple of weeks old as a publicly playable experience. If I were going to really flesh out the horror story, here - really strain these parallels to breaking point - I'd say that Palworld reflects how far "creature patenting" practices have come since Pokémon's day, and how much closer we are to treating other beings as fully modular, factory-assembled and yes, copyrightable commodities. Nintendo's original 1990s trademarks for Pokémon mascot Pikachu can be read against the grain as a piece of livestock industry wish-fulfilment. The accompanying list of applicable goods paints the picture of a fully-optimised, legally-insulated beast of slaughter - a miracle organism generated by copyright law, whose bones are lines of merchandising and whose profitable outputs are limitless: sleeping bags, electric staplers, sucrose, candlesticks, leather, fishing tackle, coffee grounds and microchips.

Where Pokémon's various storylines portray Pokémon as a protected companion species, Palworld literalises the fantasy that is "intellectual property" and wallows in the mess. The Pals are the commodification of Pokémon in-game, all of Nintendo's wider revenue streams turned inward upon the simulation that gave them life. They are the Pikachu trademark incarnate. But the Pals are even more bountiful than Pikachu, in practice, because they are both resource and workforce.

The shift from Pokémon's purebred monster-catching to Palworld's mongrel survival game pastiche is a collapsing-together of abbatoir workers with their victims - hence the Steam page's jocular suggestion that Pals could conceivably be subject to labour laws. In addition to being individual sources of food, XP and equipment, the Pals wil help you build and operate the machines you'll use to exhaust their world's riches, over and over. They'll happily participate in the construction of the very machines and weapons you use to entrap, kill and process them, asking little in return beyond a feeding trough and some straw to sleep on. Are these creatures cute? Yes indeed, in every sense of the word.