Regulate loot boxes under gambling law, Parliament committee recommends

Little patience for industry deflections

A UK Parliament committee have recommended that the government declare certain types of loot box to be games of chance which must be regulated under gambling laws. That's one of the recommendations the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) Committee published today in their report on "immersive and addictive technologies," the result of months of talking with members of the industry, academia, and public. This report doesn't mandate any changes itself but does lays the groundwork and for possible future changes. I've read a lot of government reports in my career, and this one is actually quite good. They have little patience for the industry's nonsense.

The report touches a lot of issues around gaming, from cyberbullying to the World Health Organisation codifying 'gaming disorder'. Loot boxes are the issue they have the most concrete rulings on and recommendations for.

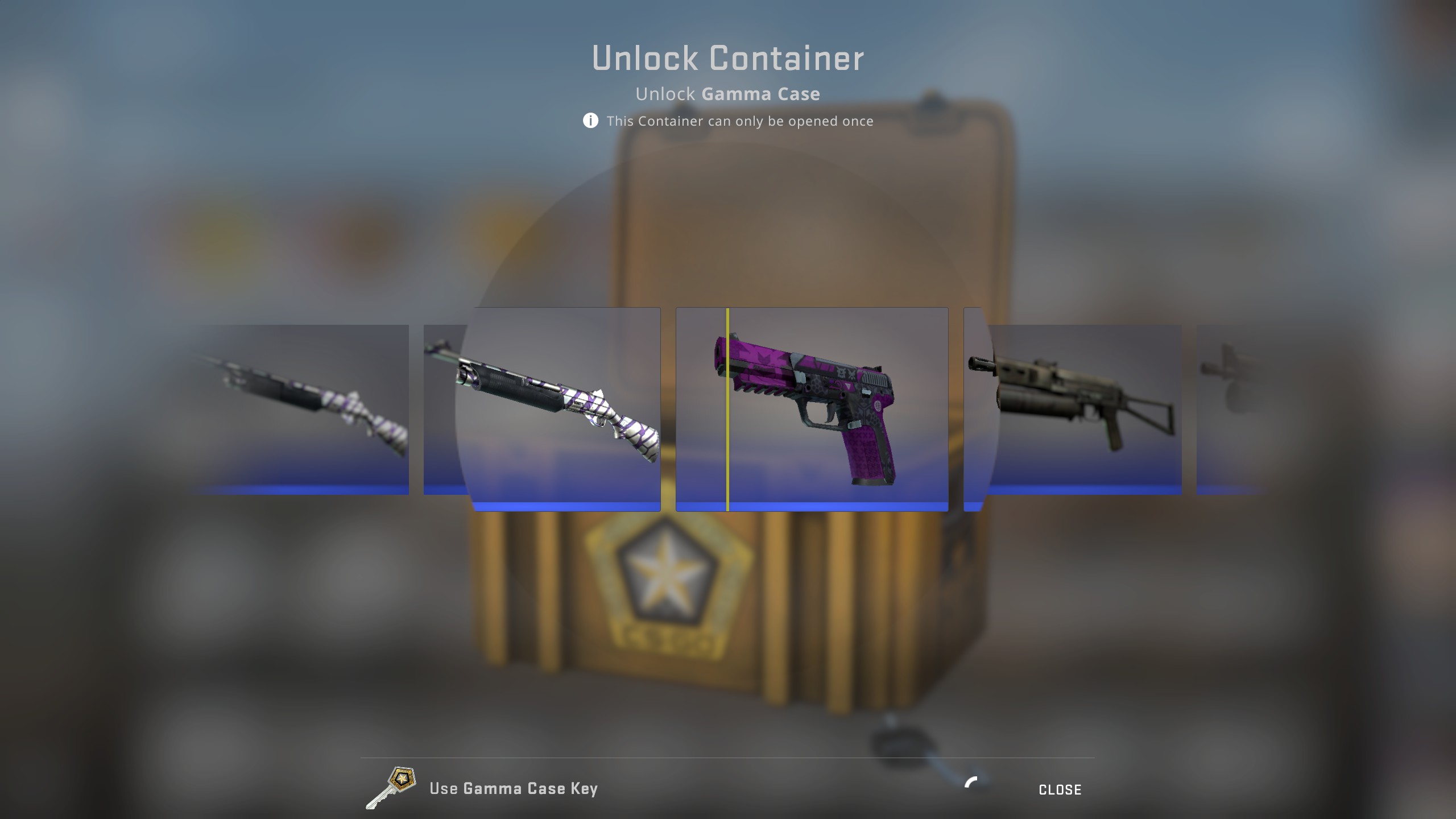

"We consider loot boxes that can be bought with real-world money and do not reveal their contents in advance to be games of chance played for money's worth. The Government should bring forward regulations under section 6 of the Gambling Act 2005 in the next parliamentary session to specify that loot boxes are a game of chance. If it determines not to regulate loot boxes under the Act at this time, the Government should produce a paper clearly stating the reasons why it does not consider loot boxes paid for with real-world currency to be a game of chance played for money's worth."

The Gambling Commission's current stance is that loot boxes can't be gambling because items have no real-world monetary value outside the game. The Commission said in 2018 that loot boxes are not gambling, though using loot box items to gamble ('skin gambling') does count when people can cash out with money or other items having value. To them, value is a real-world, monetary sort of thing. The new DCMS report disagrees, saying "we believe that the existing concept of 'money’s worth' in the context of gambling legislation does not adequately reflect people's real-world experiences of spending in games."

I agree with that assessment. Items have value to players and relative value compared to each other, even if we can't cash them out, and games manipulate us in many ways to invest in that system of value. Big publishers often try to downplay this, using terms like "surprise mechanics" for loot boxes and pointing out they're optional. The DCMS Committee say that's a little disingenuous.

"The games industry's emphasis on player choice does not acknowledge the way in which many games use random reward mechanisms that have been scientifically proven to create repetitive behaviours, and the effect that this might have on the meaningful exercise of choice. Moreover, the reluctance to discuss engagement metrics or to acknowledge the psychological impact of core design principles in evidence to us suggests that highly-skilled designers either do not know the data and psychological studies and strategies that underpin their industry or, what is more likely, do not feel comfortable admitting it in a public forum. For an industry generating such high revenues from so many millions of players worldwide, that lack of transparency is unacceptable."

As the character Sheldon from the CBS television show Young Sheldon might say, bazinga.

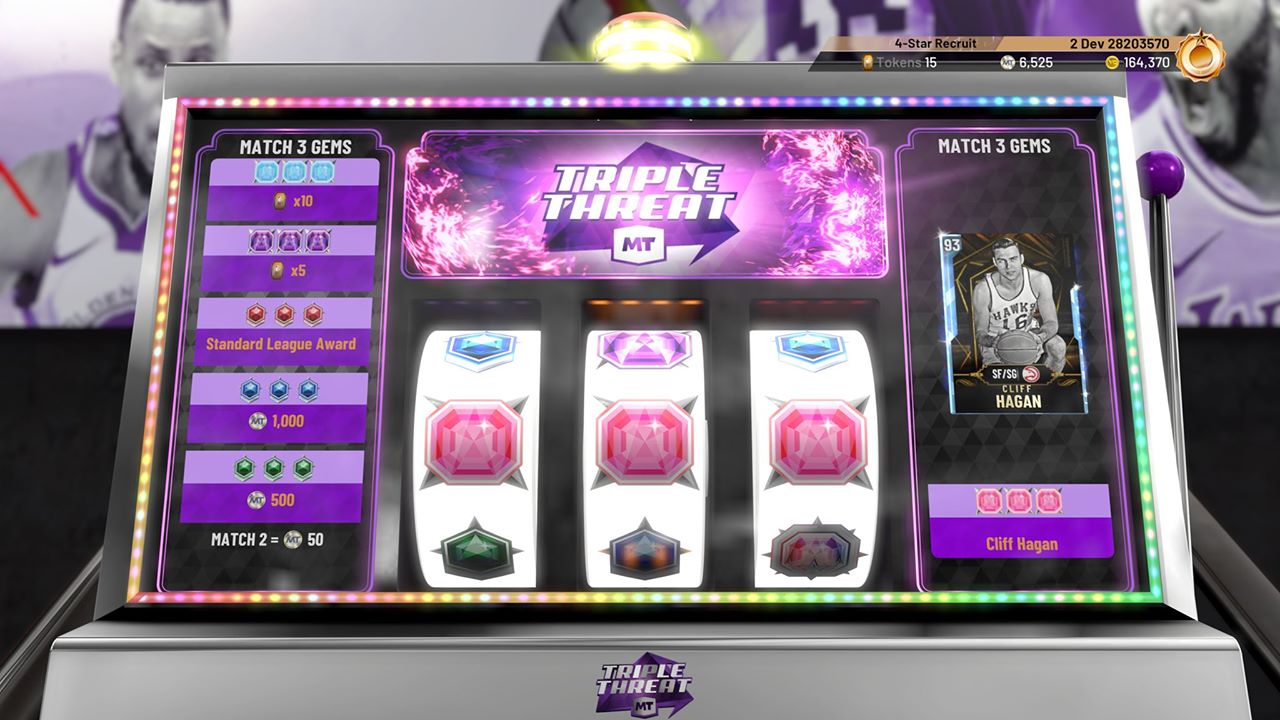

This report, I point out for a casual point of reference, comes days after the launch of NBA 2K20, a game which proudly advertises having crammed its loot box-pushing mode MyTeam with literal casino games including pachinko and slot machines.

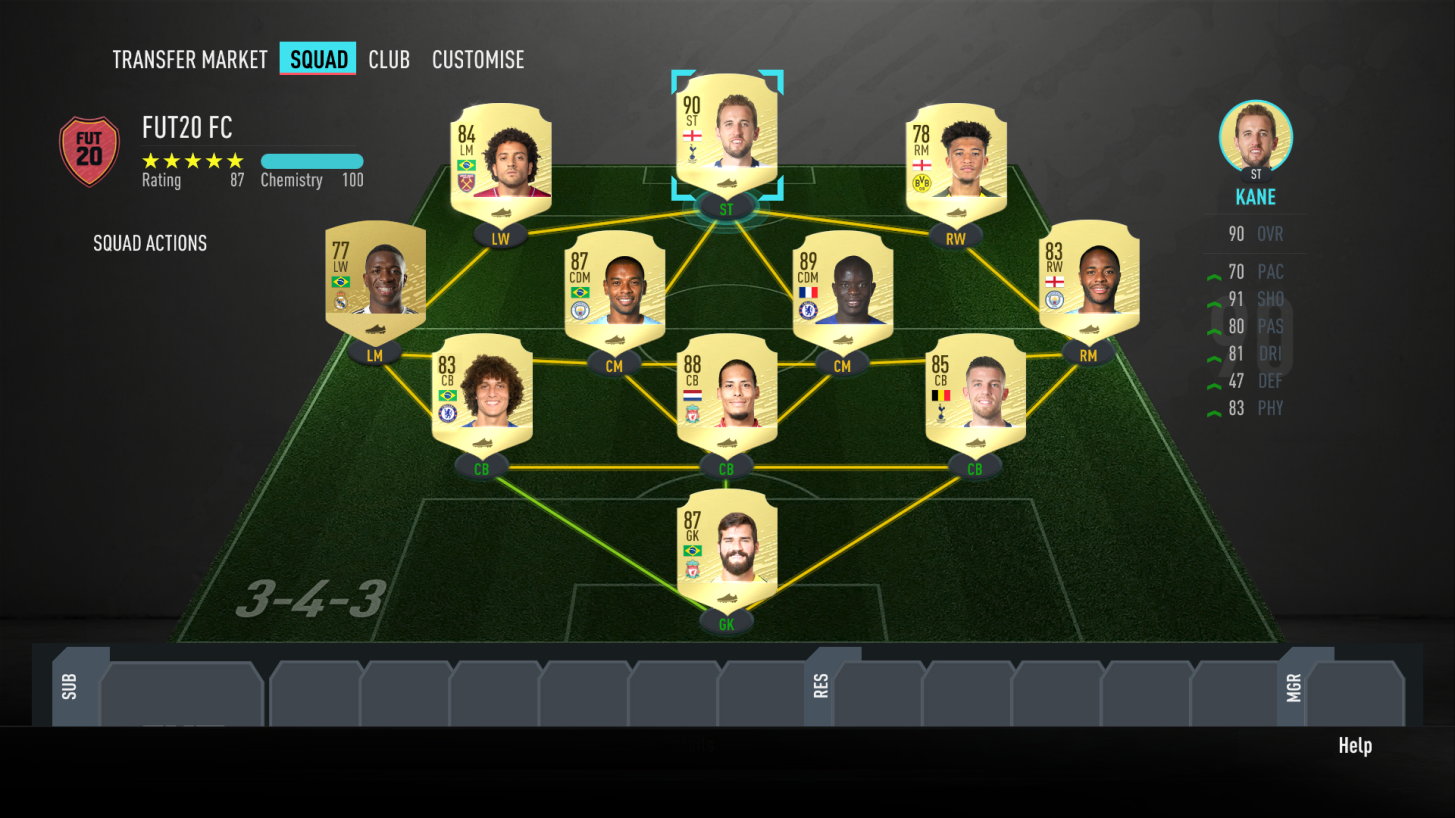

Several countries already have laws regulating loot boxes. Close to home and similar to this report's suggestions, Belgium outright declared certain types of loot boxes to be gambling. Many games have since disabled paid loot boxes for players in Belgium, including Overwatch and NBA 2K. EA tried to fight Belgium over FIFA Ultimate Team card packs and lost. Belgium is small enough of a market that big publishers are removing loot boxes rather than redesigning reward systems, but more countries going against them could prompt actual changes.

Even if loot boxes are not legally gambling, the Committee say children should be protected. They believe it's not adequately been proven that children are unaffected by them, so it's better to be cautious.

"We recommend that loot boxes that contain the element of chance should not be sold to children playing games, and instead in-game credits should be earned through rewards won through playing the games. In the absence of research which proves that no harm is being done by exposing children to gambling through the purchasing of loot boxes, then we believe the precautionary principle should apply and they are not permitted in games played by children until the evidence proves otherwise."

This connects to another big problem the committee point out: age ratings mean little these days. Age ratings and restrictions in the UK only apply to physical games, and more and more are downloadable. That's especially the case with free-to-play games, which are more likely to be supported by loot boxes too. The committee say games are largely uninterested or unable to restrict content by age anyway.

"It is of serious concern that there is simply no effective system in place to keep children off age-restricted platforms and games. The reactive way in which platforms are dealing with this problem further highlights the problems of online industries rolling out products without considering, or mitigating against, their potential adverse effects on users."

Bit wider than games, that problem.

I will be very interested to see what changes might come in the wake of this Parliament report. It cuts through the industry's deflections, though of course governments might disagree when it comes to passing laws.

The Committee also recognise that loot boxes won't be the end of the industry's shenanigans, and games could shift to new exploitative behaviours. They say that "the need for regulation to anticipate future trends in fast-paced immersive technologies is clear."

I do genuinely recommend reading the report. It's interesting, it's insightful, and it calls the industry on its nonsense.

"Data on how long people play games for is essential to understand what normal and healthy--and, conversely, abnormal and potentially unhealthy--engagement with gaming looks like. Games companies collect this information for their own marketing and design purposes; however, in evidence to us, representatives from the games industry were wilfully obtuse in answering our questions about typical patterns of play."

You can read the full report in this here PDF and even read and watch the testimonies and evidence they collected.

UK Interactive Entertainment (Ukie), our local industry body, have issued a response which broadly says don't sweat it, thanks for the notes but they're already working on things, it'll be fine.

Self-policing is very much the industry's preferred solution, and big publishers have already demonstrated a willingness to change to avoid government regulation. After previously insisting that loot boxes aren't gambling and "can enhance the experience that video games offer," America's Entertainment Software Association spearheaded a campaign for publishers to disclose loot box odds once the Federal Trade Commission got interested. They might not care about Belgium or even the UK, but the USA is a big enough market to demand changes.