Student games: stealth vomit, injury hell & sandwiches

Free autobiographical games

You may know Robert Yang through his games or his creative Level With Me series of interviews, which ran on this very website, but did you know that he is also a teacher? One of his courses at Parsons is described as "Building Worlds" and yesterday he shared some of his students' mid-term projects. They're "autobiographical" games that you can play in your browser, and the one about stealth vomiting on a crowded train speaks to me, for me and about me.

I've been enjoying a couple of these games this morning, but what I really like about them is that the students have been encouraged to "show their working". Whether that phrase was ever scrawled across my maths homework in red pen or not, I can't honestly say, but I feel like it was. I never showed my working. These are interesting experiments and at least a couple of them have enjoyable systems at their core. More than anything, I'm so pleased to see the thoughts behind the games, and the insights into the process of creating them.

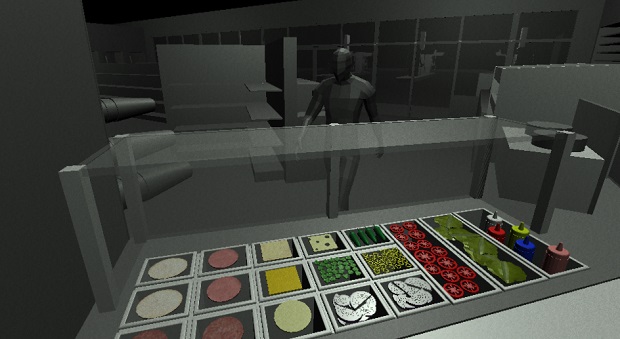

Here, the students have shared stories of theoretical next steps for sandwich-crafting and curt dialogue simulators:

"If I had more time I would add some simple mechanics that forced the user to navigate the store and parking lot. I had intended to have different tasks that the user would have to do like -- get more supplies from the freezer, mop the floor, take out the trash, etc. Additionally I would finish the model. Right now I have the general store and gas station modeled but I would want to fill it with product. I would fix the Sandwich Checking algorithm but as it would have required a pretty large change to how it worked, I did not want to start to change it and have a lot of other things break as a result. Additionally I would do a bit more work on optimizing graphics for WebGL so it looked better."

The difficulties of modelling vomit in a spooky-hilarious stealth game:

"Many of the issues I faced had to do with shooting the vomit. One major problem is that I would encounter an error where the object didn't exist to shoot. To fix this, I learned more about instantiation and how to target the rigidbody specifically if I was going to add force afterwards. I had another issue with the sight functions of the AI script not aligning with the object's rotation. To fix this, I better organized my parents and children, as well as made use of forward vectors to stay updated on where the object would be looking towards. Some other issues I couldn't fix were the flat rotation of vomit splats on everything and the hand. I wanted the hand to rotate downwards when the player shoots vomit, but the look of the hand was distorted in the camera, and my script had it rotating to angles where it wasn't even recognizable."

Failed implementation of insulin infusion mechanics:

"As it is, the game isn't fun and doesn't really do the problem of changing an infusion in public justice. Conceptually the game doesn't do what I set out to do. Which was give players an idea of how uncomfortable and difficult it can be dealing with diabetes. Instead, the game and the menu is just annoying. From a technical standpoint, all the problems I had stemmed from not importing my Maya assets correctly to begin with. This meant I had to completely resized and position all my canvases."

And translating personal pain into a vaguely QWOP-like game:

"This is a game about my experience being injured as a runner and the sort of cyclical hell that comes out of that. The idea behind the mechanic was that the more you run the more your body would fall apart."

It's easy to take this kind of insight for granted. Yes, these are small games, but they're a snapshot of young designers thinking about setting, mechanics, atmosphere, control, UI and storytelling. I remember watching Scorsese's The Big Shave back in the days when I wanted to work in film. It was fascinatingly grim and well-crafted, but how I would have loved to hear a commentary back then, or to see outtakes or more of the earlier experiments that feed into his later work.

The internet, and the generosity of developers, educators and students, gives us a line of sight directly into so many parts of the creative process that were once hidden. Thanks, internet, and people who frequent it. Sometimes - just sometimes - you're swell.