The Flare Path: Hurls Demo Charges

Simulation & wargame blather

Demos are a digital wargamer's Predator drones and PR Spitfires. They allow us to scout new battlefields safely and smartly. They furnish us with the information reviews, AARs and Let's Plays can't provide. I wouldn't be without them, yet, these days, often am thanks to the questionable policies of sector-dominating militaria-mongers Slitherine/Matrix Games.

Want to know if my Flashpoint Campaigns Wot I Think washes hogs or my Command: Modern Air Naval Operations assessment wallops cod? You could peruse other reviews, seek out Let's Plays, and scour forums for clues. The one thing you can't do is test-drive the software yourself. To discover whether my 'fun' is your 'fun', and my 'frustrating' is your 'frustrating' you'll need cold hard cash and plenty of it.

Slitherine/Matrix, the world's biggest and busiest wargame publisher, routinely fails to trial its most interesting and expensive releases. Command: Modern Air Naval Operations, Flashpoint Campaigns: Red Storm, Civil War 2, España 1936, Commander: The Great War... demo-devoid titles have come thick and fast this past twelve months. In combination with relatively high prices and restrictive distribution deals, the sad shortage of samples has to be scaring off potential punters.

In recent times the company's stance has been justified with various arguments. There's the cost-benefit one:

“[Demos] can serve a good purpose, but only in rare cases. Overall, they are a time sink for the development team with little positive result. I understand why they are popular among customers but we've found that other methods of showing and explaining the game are less costly and do a better job of informing. As always, YMMV and one size does not fit all, so there are gamers for whom a demo is the best way to decide about a game, but this does not seem to apply as a rule to most gamers.” Erik Rutins, Matrix Games

...which, in its most extreme form, implies demos actually damage sales and mislead punters:

“For the majority of our games, demos have no net advantage... They cost a great deal of time, effort, and money - while failing to really give most players the answers they want, and in fact misleading some. There is even new data which suggests that demos actually lower sales (although the statistics are pretty rough and hard to control for) - but even the suggestion does tend to go against the existing wisdom (mine included, in the past) that demos help convince people to buy a game.” Philip Veale, Slitherine

And then there's the 'Gamers are too lazy to grapple with complex trials' one:

“Demos for these huge games don't work well. The reason is that these games take a lot of effort to get you going. You need to put in the time to get something out but when you do you're rewarded with an extremely deep and fulfilling experience. When you pay for something you're willing to invest that time and push through a certain amount of frustration. When you get something for free you are much more likely to give up at the first hurdle or point of frustration as you've lost nothing. Someone who would enjoy the game if they paid for it, does not enjoy it if they get it for free as they never get into it enough." Iain McNeil, Slitherine

Expensive, sometimes damaging, often pointless... listening to Matrix/Slitherine describe demos you can't help wonder why other companies persist in producing them. Are Battlefront, Paradox, Graviteam and the like, all masochistic idiots, or is there another side to the demo debate? I thought I'd attempt to find out.

Having read, heard, and accepted variations of “Demos are costly distractions for devs” countless times over the years, it came as a bit of a surprise to hear diligent demo deliverers Paradox and Battlefront talk about the work that goes into their code canapés. According to Johan Andersson, the power behind the Crusader Kings and Europa Universalis thrones, “For us, it is not very time consuming. Usually, when you make a demo, you cut away code and features, which makes it very cost-effective to do. On average, the actual development time for a demo for our games is between 4 to 8 hours of work, and then we add QA time to that.”

Battlefront were similarly dismissive describing the process as “very inexpensive and quick, and that's even though we 'manually' produce demos. What I mean by that is that we compile special subsets of code to create a demo with specific features, and rip out what isn't needed. There are even easier ways to do demos nowadays, as many companies offer full versions packaged as trials that run for a limited time only, so they don't even need to recompile (and retest).”

Are BF and Paradox just reaping the rewards of years of demo design experience? Possibly. Novice demo-ists 2x2 offer a different perspective. Fashioning a Unity of Command tempter was, according to Tomislav Uzelac, "definitely non-trivial which is why it took us a few months to create one.”

Graviteam's Vladimir Zayarniy also admits there was toil at the beginning. “Once upon a time, it was a long, hard process but over time we have automated the assembly process and now it takes only a few hours. Testing and downloading to the site takes longer!”.

Whether they take weeks, days, or hours to fashion, the fact is demos are developmental distractions. Why bother making them when one of the industry's most experienced operators claims they usually have “little positive result” and might “actually lower sales”?

Well, maybe because not everyone agrees with Matrix's extremely pessimistic market analysis. Johan again: “A demo is one of the single most effective things we can do to promote our games... When we release a demo, pre-orders increase. We can see sales statistics live on Steam and we can definitely see the connection. Demos drive sales”.

The Combat Missionaries also claim a direct correlation between demo releases and sales spikes. “Historically there is no doubt that the very first Combat Mission Beyond Overlord beta demo has been the most successful for us (It was the right time and the right place, and it has provided the base for Battlefront's success in the years since.). However, the demo for our most recent Combat Mission Battle for Normandy series caused a big influx of new players.”

Even when sales stats are hard to come by or less convincing (2x2's Tomislav believes only 14% of the players who installed the UoC demo ended up buying the full game), demos can earn their keep as confidence builders, publicity generators, and problem preventers. Johan described how demos helped restore confidence in the stability of Paradox products after a couple of rough releases, and went on to point out that they can lighten the burden on support teams by ensuring customers don't buy software their systems can't handle.

For Vladimir a trial is a tool for spreading the good news about engine upgrades. "We've updated the demo after every significant change to Graviteam Tactics - after the overhaul of the operational layer to feature more units, after we implemented wired communication simulation and added restrictions on orders frequency in tactical battles... Hopefully players that are not happy with aspects of the original game, will revisit and find something new in the updated demos.”

My correspondents were also keen to justify their trial releases on transparency grounds. “Buying a game without being allowed to try it is like buying a car without test-driving it or a house without seeing it yourself and getting an inspection. Of course, if a game is on sale for a few dollars, it may not be as important, since that amount of money may be trivial. But if you are debating spending 40€ or more on a title you are not 100% sure about, then I know that I´d definitely like a demo, before I spend my money.” Johan's sentiments are echoed by Battlefront. “We use demos to make sure a game runs on a user's computer, and to make sure people know what they are getting before they spend their hard earned cash.”

Whether created for selfless or self-interested reasons (or - more usually - some indecipherable combination of the two) a demo can't help but radiate respect. While some devs and publishers seem to believe we're too lazy or impatient to properly engage with the demos of heavyweight games, others have enough confidence in us and their products to risk rejection.

Graviteam are plainly willing to accept that a portion of the people that install the generous

Graviteam Tactics: Operation Star trial will probably (and tragically) surrender after struggling with night battles and the blizzard of tutorial tips (Both of which can be turned off via Options!) and thus never reach the Tiger-infested Shangri-La beyond.

Paradox are probably aware that the genealogical genius of Crusaders Kings 2 only clicked for some users after hours... days of exposure, but that hasn't stopped them letting the curious investigate investiture and inbreeding.

Combat Mission has got weightier and more intricate with each passing year, but BF are just as confident you'll find yourself hopelessly hooked after spending an afternoon puncturing Panzers and storming sunken lanes.

Slitherine/Matrix, if you're reading this, I urge you to give demos a second chance. There's ample evidence that free fillips don't have to be costly or counter-productive, and, more importantly there's an army of uncertain punters out there eager for the sort of high-class personalised intel that only demos can provide.

The Flare Path Foxer

Last Friday's quizbusting Quarrymen were SpiceTheCat, skink74, Matchstick, FuryLippedOctopusSquid, Showtime, mrpier and Mr-Link. For spotting the Beatles theme, Spice wins a year's supply of semolina-pilchard flavoured Flare Path flair points.

1. Rice (Eleanor Rigby)

2. Krag-Jørgensen 1892 (Norwegian Wood)

3. Diamond Katana (Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds)

4. Upside-down Union Jack (Help)

5. Walrus-class submarine sensors (I am the Walrus)

6. Pepperbox pistol (Sgt. Pepper)

7. Ryde station, Isle of Wight (Ticket to Ride)

8. SR-71 Blackbird (Blackbird)

9. Slingsby Kite (Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite!)

When FP was a lad, he played Top Trumps at the very highest level. The infamous brawl at the 1982 TTIO in Tokyo? FP threw the third punch!

Like many of his peers, his involvement with the sport began in the playground. He specialised in 'Sumps', a game variant where a contestant's card knowledge and mathematical prowess are tested simultaneously, usually for money. On one memorable occasion during the stormy summer of 1979, he won £30 on a single twenty-card, five-pack accumulator. Heady days!

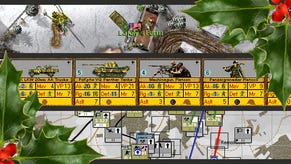

Try Sumps yourself by adding together the seven stats erased from the cards pictured below. Think that tank has a gun calibre of 88, that bomber has a wing span of 32.60, and that loco is a Type 47? Add the stats together (88 + 32.60 + 47 = 167.60) and move on.* The supplier of the first correct total will win a rare vintage Flare Path flair point made from Blakeys, Bazookas and bravado.

*Early Top Trumps packs were littered with factual errors but the stats scrubbed from these cards are all accurate.