Wot I Think: The Ice-Bound Concordance

"We were collaborators. One of us was a ghost."

Most of Carina Polar Research Station has been buried beneath the ice. It was inevitable, really. Over time, the heat and weight of the base caused it to sink slowly, and rather than digging it back up, the next teams simply built on top of it. It sits like a snowy layer cake, each sunken base becoming increasingly abandoned, aged, as you descend. And that’s what you do in The Ice-Bound Concordance [official site]: starting from the very top, you emerge from a blizzard and make your way down through the past to the very bottom of Carina Station, and the secret that it holds.

Except - hang on, that’s not quite right. That’s not right. Let me try that intro again.

Tethys House, a fictional publishing company, can do something remarkable. Using a combination of various partially disclosed methods, they’re able to resurrect long-dead authors as artificially intelligent “simulacra” capable of writing brand new stories. The author “Charles”, for example, has just finished Little Pip Popplewell, which includes “two custom roles for personalization through our You Pick The Cast program”. This is obviously controversial, with living authors decrying the simulacra as “formula fiction” and calling for a renewed focus on craft. Tethys House have an ace up their sleeve, though. They’ve managed to obtain brain scans of Kristopher Holmquist, an author whose gigantic popularity only emerged following his death.

Tethys have built a simulacrum of him and set it to work finishing his infamous unfinished novel, Ice-Bound, which currently only exists in the form of fragments and notes, each contradicting the other. This is no small task, and so the “KRIS” simulacra has been assigned a human partner to help it compile the pieces of Ice-Bound into a finished and marketable novel. It is unclear whether the “finished” or the “marketable” aspect is more important.

So that’s where you come in. Descending through Carina Station, yes, but not as a scientist or researcher - you’re instead something like a co-writer, trying to make sense of various fragments of plot as their long-dead creator politely talks you through them. “What did you think I was going for here?” he’ll ask, and you’ll have the opportunity to affect the story both directly (“I think the Professor should slip and fall,”) and thematically (“I feel this is a chapter concerned with spiral imagery”.) As you and KRIS mirror the character’s explorations deeper into the station, you gradually refine the story more and more into what you feel it should always have been about.

As you might have noticed, this is a game that defies easy explanation. Part of that comes as a result of its format; the first two chapters of Ice-Bound are free, but to play more you need to purchase a book. An actual, real, hold-it-in-your-hands book, crammed to bursting with journal entries and chat logs and newspaper articles. Many of these don’t make that much sense at first. You’ll find references to characters in Carina Station that you know shouldn’t exist, messages between people you’ve only vaguely heard of. As the game progresses, though, the contents of the book (called The Ice-Bound Compendium) begin to gain more and more meaning. It’s a key, really, and to explain how it works, I’m going to have to -- okay, bear with me here, I’m going to try and describe how this game actually plays.

I should probably start by saying that in a brilliant example of pacing and tutorial design, most of what I’m about to muddle through is communicated very clearly in play. Any time I felt like I was losing a mechanical thread, the game would reinforce it, or outright ask if I was confused and steer me back onto the right track. As the player descends through Carina Station’s layers, they encounter the various fragments of the story Holmquist managed to complete. At first there are three or four fragments per layer, each represented by an object. A pressed rose, for example, might lead to a fragment about romance; a bottle of pills tells a short story about illness.

Not every fragment can make it into the final story, though. That would be a mess. To counter this, the simulacra gives you a set number of “lights”: little whispering, glimmering circles that, when placed over fragments, activates them. In this way, you can only activate a few at once before you run out of lights. These lights aren’t expended, though, only assigned, leaving you free to change your mind about what a layer’s fragments should be until you descend. Here’s a picture. I hope the picture helps. Good grief, this is fairly tricky to explain.

Different combinations of fragments unlock different “events” - the fragments “Felipe is claustrophobic” and “the Professor is ill” might lead to “Felipe becomes trapped in the air vent”, for example. In turn, these events can combine to make endings. One of them might be “Felipe freezes to death in the air vent”. That seems really quite unfair towards Felipe. Let’s re-arrange some lights. Okay, now the Professor’s no longer ill, and she gives Felipe the strength he needs to leave the air vent. They descend together.

Hm. I thought it was interesting that the Professor was ill. It complicated her motivations for joining an arctic expedition. Can I prevent Felipe’s death and still have her be ill? Let’s re-arrange the lights. Ah, no, Felipe’s dead again. And so on.

At any moment, you can read the individual paragraphs described in the fragments, and alter tiny non-mechanical details. Did the Professor comfort Felipe “firmly” or “desperately”? Did the wind outside “howl like an army of wolves” or “whisper maliciously”? Sometimes the prose verges on purple, and this bothered me at first until I remembered that I was reading early portions of a novel, whose author died before he could get them to a place he was entirely happy with. Sure enough, the Compendium makes reference to the variable quality of Holmquist’s fragments.

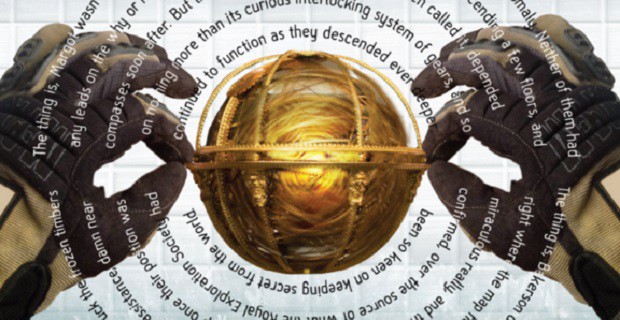

So, the Compendium. The KRIS simulacra might not be a human, but it (he?) is still concerned with finishing the story properly. He (it?) is, in many important ways, a facsimile of the author who left Ice-Bound behind. So rather than just throwing in fragments on a whim, he asks if you can find some proof from the notes contained within the Compendium that you’re guiding the story in a direction he’d previously considered. “It sounds like you’re talking about themes of Trial By Fire,” he says, and sends you off to find evidence of that within the Compendium. You leaf through the pages until you find something that you think matches that, and then, in a brilliant touch, you hold the book up to your webcam and let KRIS see it. In the grainy image on your computer screen, the page of the book comes alive. It’s overlaid with new text, or a message dramatically changes, or an animation splinters across it. Content that the Compendium supports your decisions, KRIS “freezes” the layer, stopping you from enacting changes, and descends to the next. The story begins to take shape.

Early on, as I agonised over the combination of lights, KRIS offhandedly chimed in with something like “you think this is difficult? Think about the amount of permutations there’ll be further down”. He was right. The deeper we travelled, the more the scope of the game impressed me. Tabbing into the paragraph view, you can see a breakdown for the exact reasons sentences have been chosen, altered, modified. The more I pressed for the story to contain elements of the fantastic, the more KRIS seeded fragments with impossible stairways, twisting libraries, figures made from icicles.

A love triangle I’d accidentally wrangled from the light permutations was forgotten about for three layers then re-appeared suddenly further down. When I realised quite the extent to which the story was procedural and responsive, it felt like a dizzying pit had opened up. How was this made, I began to wonder. What needs to be done to make a game like this?

The answer, at least in part, involves compromise. Even at its best moments, the story remains fragmented, crystalline. Plot-lines don’t develop or conclude on a particularly large scale, instead being reflected in repeating themes and motifs. To an extent, this works very well: the game was never about writing a story so much as corralling elements of one, and there’s a certain scattered poetry in the way the game introduces elements only to largely forget about them. I wish, though, that I learned what happened to Felipe in the air-vent, or what was in the box Ethan fished out from the ice. Even as this frustrated me, though, I’d feel some small but significant change ripple through the game from a choice I’d made, and I’d press on deeper into the station.

At the heart of all this is KRIS, and the memories of a man called Kristopher Holmquist. Just as reading any other book begins to tell you about its author, directly or indirectly, elements of Kristopher begin to seep into the story. A visit to an actual polar research station. A shopping list. An answering machine. The author takes shape in front of you, and you begin to reconsider some of your responses to his questions. After learning through the Compendium that the living Kristopher could always have used somebody willing to challenge his ideas, I halted when he suggested I take the story to a place I wasn’t interested in. “I’m not sure if that’s right for this,” I said, and he considered it and capitulated. Later, he grumbled when I suggested something. We were collaborators. One of us was a ghost.

When I’m editing, I’m often overwhelmed. At first, writing is an additive process; there is a blank page, sentences fill it word by word. Ideas stack on top of each other like Jenga pieces. Editing is different. I squint at the Jenga tower I’ve built and realise that the piece two rows from the bottom needs to go on the top. The tower falls down. I put it back together again except this time I realise I’ve forgotten three bricks, so place them haphazardly on top. The tower falls down again. Ice-Bound is a game that, more than anything else, captures this feeling of editing.

I’ll position one of KRIS’s lights and learn about a new character, pull a face. They seem fun, but push the story too far in one direction. I add another light. Oh - what if they’re friends with Bakerson? That might mean that he stops them from opening that frozen door? Maybe the story should have more elements of horror. Is there any way I could remove Bakerson altogether and strand this character in the station?

In two layers time, I’ll realise that I never found out what was behind the frozen door, beyond two sentences describing the character’s face, twisted in fear.

In three layers time, the stranded character’s loneliness will have propagated downward through the story in a way that surprises me.

There’s more, of course, but to talk about it would rob it of its surprises. The story gradually opens itself up, approaches stranger and more difficult themes. And then it ends, with a simultaneous flourish and abruptness that left me feeling very strange. In a few brilliant, awful final moments I realised where I’d made mistakes as a player and an editor, where I hadn’t thought hard enough, worked things through. All stories have to go somewhere, all polar research stations have secrets buried at their base. But the abruptness - it bothered me, kicking me back to the menu screen and flashing the “new game” button. Here, the game’s fragmented procedural nature acts in its favour; who would inhabit the base on my third playthrough? My fourth? I can’t help but feel, though, that in the end, the lack of a particular conclusion is sorely missed.

When I finished the game, I picked up the Compendium and turned to a random page. I recognised the names of some characters, and peered closer. Flipped the page. In a little inset was something I hadn’t read before. I must have missed it earlier, and my eyes widened. It didn’t dramatically change the story or dazzlingly recontextualise something. Instead, it added a tiny fragment that, the more I thought about, added to aspects of what I’d played. A little light had turned on, enacting a change that rippled down through the story. Sitting here in a coffee shop, writing these lines, it’s still rippling. Thawing the ice, down in the depths of the Carina Polar Research Station.

The Ice-Bound Concordance is available now.

Jack de Quidt is a writer currently working at Crows Crows Crows on games like Dr. Langeskov, The Tiger, and The Terribly Cursed Emerald: A Whirlwind Heist.