The It's Winter and Routine Feat developer explains Russian sadness and powerful moods

If you're cold, put a coat on

Alexandre Ignatov makes strange, quiet, melancholy worlds to explore. He calls them “sad3d”, also the name he publishes under on itch.io. But Ignatov has a whole back catalogue of these games, and they’ve only been growing larger and more complex with time. If you’ve been reading RPS closely you might know of the most recent ones, It’s Winter and Routine Feat.

Ignatov's games have a depth of interaction you don’t see outside of immersive sims, yet no pressure to really do anything, and a distinctly Russian identity. I found I couldn’t stop thinking about them, so I contacted Ignatov to ask about their origins and inspirations.

Long fascinated by games, Ignatov began using Blender in middle school, and continued doing 3D modelling into university. When he finally showed close friends some of the games he had been making with his models, he was surprised by the positive reaction. Although he began to publish some of his work after this, he remained driven but private, rather than targeting the path to fame and fortune.

Ignatov says making games is primarily his hobby, and how he expresses himself. “I chose games as my art because it is my dream since childhood," he tells me. "I like the way you can create an incredibly powerful mood using space, sound and lighting in games; I hope that one day I will be able to awaken deep and maybe hidden emotions in people with my art.”

Ignatov tries to convey an emotion to the player with each game he makes. With After Midnight, where you awaken in a cosy cabin above the snowline somewhere, it was "comfort and a little intrigue", the dense, spooky forest in Nemus Immensum was "an attempt to find something that does not exist", and there was "a love for one’s place and a fear of the world around" in the lonely little room in Solitude. Much of Ignatov's work is "not meant to be fun, addictive or pleasant" in the conventional way games are supposed to be.

It's Winter was part of a multimedia project inspired by a poem by Ilya Mazo. "It’s Winter is something that [Mazo] and I described as 'Russian sadness'" he explains. "Being unable to do anything in particular; eternal night, snowfall and loneliness in a small apartment.” For Routine Feat, meanwhile, he expresses a desire “to talk about the craving for nature, looking for freedom and at the same time -- the inability to get out of the 'work – home – work' cycle.”

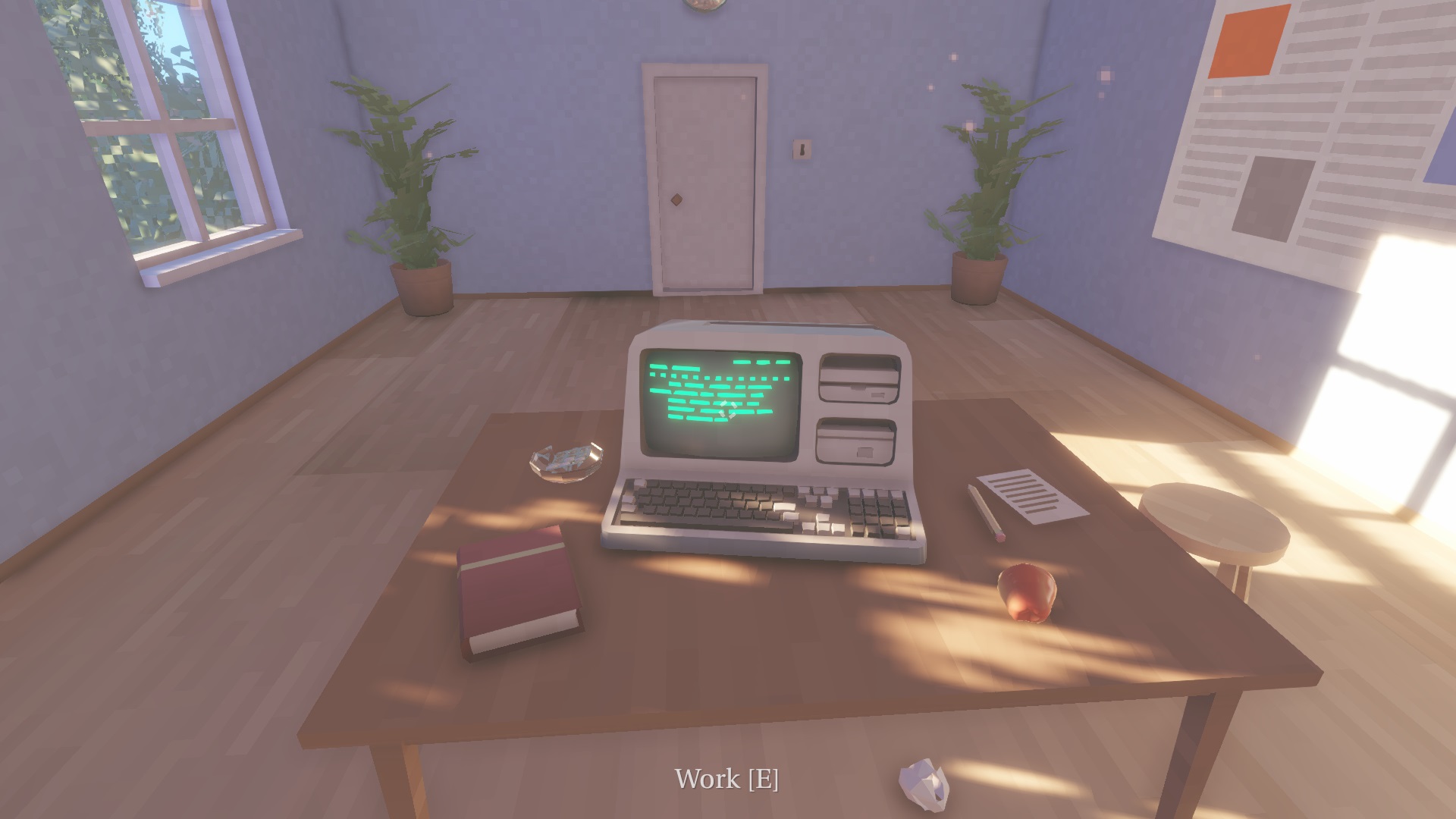

Routine Feat is basically the same stolid blocks of flats as It’s Winter but, well, in summer, and it was using the same map that allowed Ignatov to add all sorts of new elements to the simulation, including a workplace and a series of surreal dreamscapes. But Ignatov tells me that he had actually begun the game that would become Routine Feat first. The group making the Winter multimedia project approached him and liked the idea of what he had, but wanted something gloomier and more oppressive. He shelved the sunnier look and did a wintery re-skin before coming back to it as a solo project. As a player, I really enjoy getting to know this same space intimately and across seasons -- although I still always feel on the verge of getting lost in it.

Ignatov says that he thinks getting lost in this kind of game is a part of the game itself. “A small map, relatively slow movement speed, a need to wait for the bus at the bus stop and the possibility of getting lost, and even to fall through the ground and walls sometimes -- all of this, I think, stress those feelings of the character, [the] feeling of isolation in a small town, boredom and being lost in general.”

Exploring these worlds, and finding all the combinations of possible actions, has become a huge chunk of the enjoyment -- in part, perhaps, because cooking an egg on toast in a silent apartment transfers very well to social media. But not everything does what you think it might, and a lot of things have no actions. Ignatov confesses that he is “no programmer” and says that much of what he wants for the games he finds very hard to implement.

“I would like to learn coding at a higher level and thus get more capable in making desired game mechanics,” he says, adding that he wants to "achieve a smoother and more relaxed exploration in my games", which means he'll have to study his craft more. I am also learning to model more complex objects, rigging and animation. I hope to create more dynamic worlds in the future; I really want to breathe more life into them.”

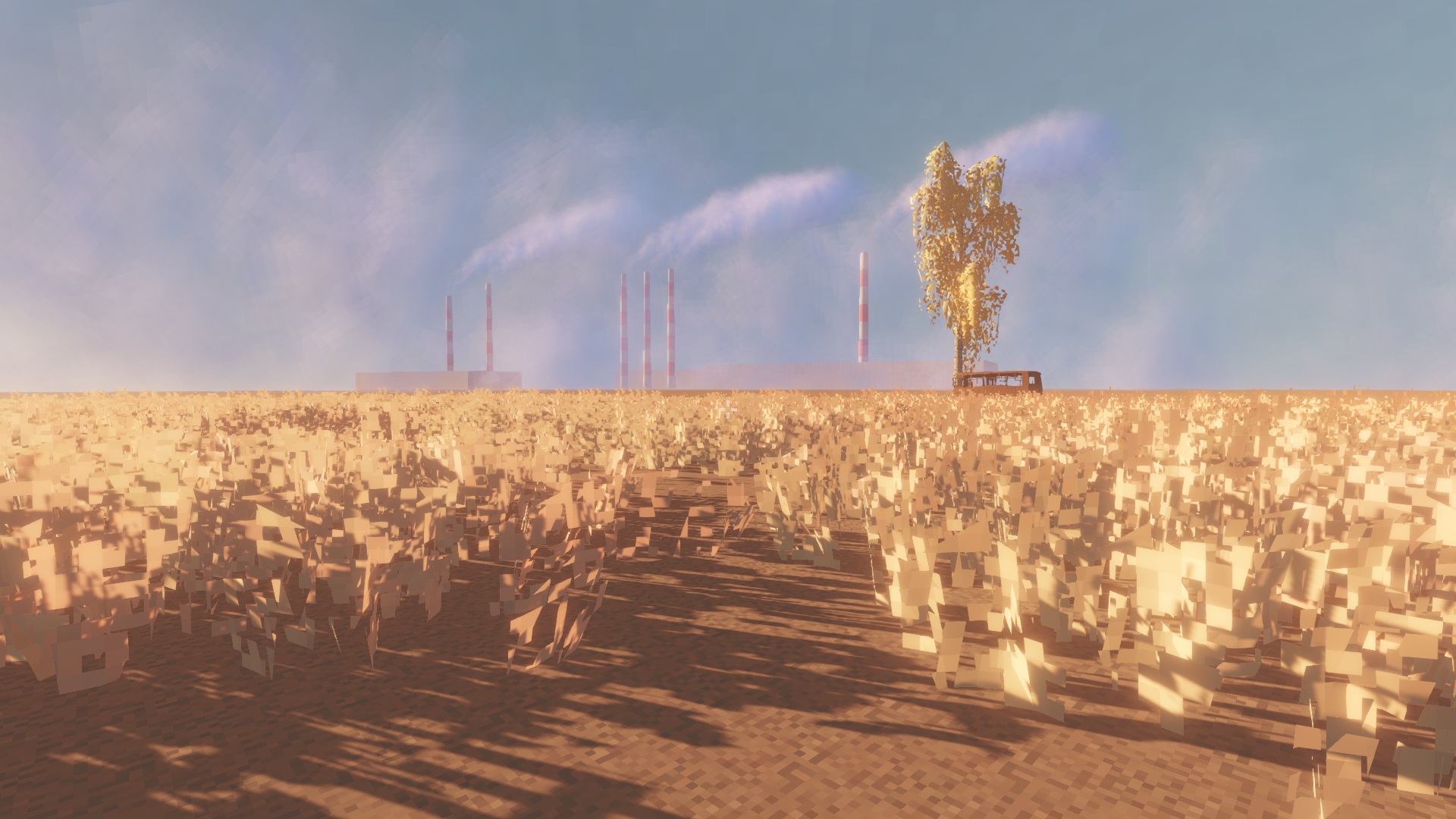

I wouldn't say they're entirely devoid of life as they are. Routine Feat's dream sequences, extremely dramatic and surreal landscapes breaking up the mundane apartment complex, are, to me, the most interesting part. I can’t stop thinking about the dream of fields, where you stand in endless, swaying, fields of grain, everything else around -- the apartment blocks -- has seemingly been levelled. But for one thing. Throughout the game you catch sight of power plant towers in the distance that you can never reach and in the dream, on the horizon beyond the fields, the power plants still tower over you. As you head towards the road, you see the bus you take to work every day crashed into a tree and destroyed, long ago rusted out and with grass growing through it.

“No, neither in dreams nor in reality you can't come close to them," says Ignatov. "In the town in which I live there used to be a factory and it had those towers. But over time they leaned and finally were torn down.”

Ignatov doesn't can't really give much analysis of the dreams because he made them "spontaneously", each one taking roughly two or three evenings from concept to finish. "There is no certain interpretation to them," he says. "Perhaps they have no definite meaning, just mood, and the character simply rests in them from his everyday life among the panel houses.”