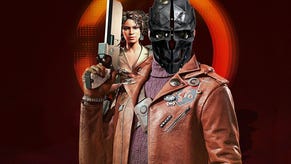

Interview: Unmasking Dishonored's Harvey Smith

Putting It All In Perspective

Dishonored is pretty great. Incredible, even – at least, in places. We've had many wordthinks about it, and odds are, the future will bring many more. Those, however, are for another time. Today, we're giving the angular, Viktor-Antonov-designed spotlight over to one of the main minds behind the whale-powered wonder, Harvey Smith. From System Shock to the original Deus Ex to an ill-fated Area 51 reboot to a canceled RTS and even a brief stint in mobile gaming, he's seen all corners of the gaming industry. But – dare I suggest it – there's far more to life than videogames. So I sat down with Smith to discuss how and why he does what he does, and as it turns out, he may well be just as incredible as the game he played a crucial role in creating – if not more so.

There are some people whose entire life stories come tumbling into view the second you get a good look at them. What they're wearing, the way they move, how they introduce themselves, how they style their hair, where their eyes dart, where they don't. No, it's not generally a good idea to judge a book by its cover, but the cover's there for a reason. It's a window into their world, a shrieking neon sign of history.

Harvey Smith is not one of those people.

Sitting down across from him in a dimly lit corner of an ornate, extremely spacious hotel lobby, it strikes me just how much he stands out – precisely because he shouldn't stand out. He's dressed plainly, clad in a black T-shirt and well-worn blue jeans, and reclining casually in a floral print chair. This is the co-creator of Dishonored and one of the principle minds behind Deus Ex – among many other things – but unless you knew him, I doubt you'd be able to pick him out of a crowd. But then, they say the ones with the least to talk about often speak the loudest. Meanwhile, Smith – after all he's seen, done, and been through – has far more to say than most. So instead of getting a mohawk and a megaphone, he creates.

But where exactly did his drive to spin Dishonored's taut web of brainy, freeform stealth and all-out chaos come from? Well, like a significant number of people, he began life as a child. He always had a playful streak, too, but even back then, he did things his way. “Basically, I took a Robin action figure and put him in gray and black tights,” Smith reminisces. “He had the little domino mask, and I added gray and black tights. I thought the boots from the Tin Man were cool and gray, so I put them on. My grandmother came in the room and looked at the action figures I was playing with, and she said, 'Oh, no, you broke your toys!' I said, 'No, I made a new one.'”

Obviously, Smith was a bright and creative child, so I ask whether or not that carried over into his school work. Turns out, it didn't – but absolutely not for the reasons you'd expect. Plenty of brilliant kids slip past the modern education system's suffocatingly narrow net, but Smith's youth was far from typical. Tragedy struck early, and it was savage in its attack.

“My mom died when I was six,” Smith explains, clutching his arms and breaking eye contact. “She OD'd in front of me. My dad killed himself. Those two things didn't happen in a vacuum. There was a lot of trauma that led up to those things, a lot of chaos. Everything would have been fine. I was just a blue-collar kid in a small Texas town. It probably even would have been fine with the drugs and stuff, and the physical abuse. But when you have a parent die that early, it's shattering. Especially your mother. It's a lot to come back from. I was that kid. It probably led to writing and escapism and all of that stuff.”

“Teachers always said the same thing about me: 'When I talk to this kid, it's amazing. When he's really excited about something, it's amazing. But if he's not, he barely passes. He isn't achieving what he could achieve.' I think sometimes kids in school are dealing with depression and they're checked out. Only when somebody reaches them, or when they're talking about something very exciting, do they light up. That was me. I was not a very good student at all.”

I start to see it. When he gets onto a topic he's really passionate about, his entire demeanor changes. He leans in, he talks much louder, his eyes light up like wild excitement is trying to burst forth from them in laser form. By no means is he a sad or dour person – quite the contrary, in fact. And he's very conscious of that. His youth, he notes, definitely shaped him, but that didn't have to be a completely bad thing.

“Kids are good at figuring out how to survive in their environment,” he says. “If you ever talk to the kids of alcoholics, they generally are very good at understanding a social situation, because they had to read people constantly. There's that. If you talk to kids that are alone a lot, or dealing with something very consuming, very negative, very depressing or whatever, they find a way. People cope. They adapt. So I think fiction and games... I think a lot of people just appreciate those things, and then other people are consumed by them, drawn to them. They use them in some way that helps them.”

That in mind, it only seems natural that Smith eventually went on to craft the very type of thing that gave him such a powerful outlet when his life took a turn for the worst. It was not, however, a direct A-to-B path. His first stop after leaving home was actually the Air Force, of all things. He needed to get away, and the Air Force provided a consistent, reliable way of doing that. “I ended up going to Germany to do this satellite communications work, living in this little village 30 minutes away from the base,” he recalls, now visibly animated. “My ex-wife and I toured Germany, and it was great. I went to university there. I was a lit major and a psych minor. I didn't graduate, but I went to school for several years. I have to say, the whole experience was fantastic.”

“At one point I went to Saudi for a while. Between Desert Storm and Operation Southern Watch. We were enforcing a no-fly parallel or something like that. A line that Saddam Hussein's planes weren't supposed to cross. The stuff was fascinating.”

But after six years of that, it was time to move on, and Smith was once again without a handy golden arrow or a series of invisible walls to guide the way. It was only after a good friend who worked at Origin (the real Origin; not the EA download service) suggested Smith turn his videogame obsession into a career that he decided to set up shop in Austin, Texas and give it the old haven't-quite-graduated-from-college try. What ensued was, well, probably worthy of its own comedic Hollywood montage.

“I tried for six months to get a job there as a designer or a writer,” Smith continues. “I played in a Shadowrun campaign that met in the boardrooms after hours. I played multiplayer games in the QA test lab. I played on their softball team. I went skydiving with Richard Garriott. There was a team skydiving event that I wormed my way into. Jumped out of a plane with those guys in San Marcos. And I still couldn't get a job. Then there was an ad in the paper that said, 'Wanted: Testers. $7 an hour.' I took it.”

It was a humble beginning, to be sure, but Smith was fortunate enough to find himself surrounded on all sides by greatness. Even as a tester, he worked on Wing Commander and System Shock. Not a bad way to start, huh?

“I can't complain,” he replies when I point out that his time at Origin ended with the tumultuous cancellation of an RTS called Technosaur. “I did stuff that was amazing. I worked with Richard Garriott a little bit. I worked with Warren Spector. I got to see every aspect of game development. I worked as an AP. I worked as a designer. I worked as a tester. I worked with the translators for a while. I moved around a lot in there. People really responded well to me. I was given a lot of opportunity based on the work I was doing.”

All this time, I'm continually stricken by Smith's ability to put a positive spin on life's most nauseating ups and downs. It's not denial or anything like that, either. But whether life hands him lemons or a box of live hand grenades, he'll find a way to make lemonade. Even so, Smith won't deny that his early experiences strongly influenced his later works. In a lot of ways, however, that made Deus Ex an ideal project for him to really flex his creative muscles on.

“I still, to this day, love games where I'm in a dark, creepy, scary place, and I'm underpowered, and I'm facing monsters, and I master those monsters by defeating them with trickery, stealth or whatever,” he says, a grin creeping across his face. “I think there's still a component of that, that is... The reason that's soothing or titillating in some way is that it's based on some pattern that a lot of people share. Anybody who's gone through something like that when they're very young, in a formative time.”

Deus Ex, however, also allowed Smith to reconnect with his background head-on – or rather, to express it in a more direct, contemplative way. “One of the missions I worked on in Deus Ex is the mission where Nicolette DuClare goes back to her house, six months after her mother's assassination,” he explains. “It's the first time she's been there, and she's kinda sad about that. So you explore her empty house with her. And by the way, there's no monsters that attack in the house. There's no enemies. It's just an empty house. I had to push for that on the team, because everybody was filling all the rooms with bad guys.”

“It just resonated, right? It's not so much that there was a direct connection to any specific thing [that happened to me]. It's just that when I think about an idea that's appealing to me... You meet this young person and she's tough on the outside, but she's really hiding the fact that six months ago her mom was killed, and it's really affected her. Going back to the house is a big deal. It's where she lived with her mom, and you're exploring this empty house as she roams from room to room making comments with you as she goes. She follows you and comments.”

And while Deus Ex's development wasn't without its moments of drama and disagreement, the finished product went on to become a medium-defining classic. But even that didn't catapult Smith down the road to easy street. Good times, unfortunately, were followed by a pretty lengthy spell of bad.

“I was disappointed with decisions that we made on Deus Ex: Invisible War. Things also went very badly at Midway [with Area 51]... Area 51 was just super-troubled development. It was a very large organization. It was hard to get anything done. Nobody was really empowered, I think. After I was gone - after I got fired, frankly - all of their studios shut down. One thing was not the problem. It was not isolated.”

Smith, however, eventually bounced back. He kept on pushing forward, and ultimately, it led him to a job at Arkane meticulously crafting his dream game alongside co-creative director and good friend Raphael Colantonio. It's been a long road, certainly, but Smith chalks his recent good fortune up to the fact that he never lost sight of what actually mattered.

“You know, I just love games,” he enthuses. “I love talking about games. I love playing games. I love designing games. I've always believed that you should ignore all that [negative stuff] and just keep working. It's a good philosophy. On our worst day in video games, we're doing intellectually and creatively stimulating work.”

“If you've ever had anything bad happen to you for an extended period of time, it relativizes things. From that point forward, you know what a good day and a bad day are. A lot of people have never had much of anything bad happen to them. They don't know what a good day and a bad day are. 'Oh my God, this is terrible, our plane's delayed. We're going to get to Italy later than we thought!' Oh God, your life is terrible. I think that's one of the things that helps you deal with adversity. Keep an idea of the relative scale of adversity and how good you actually have it.”

Similarly, when I point out that Dishonored is an exception to triple-A gaming's sea of same-y, too-safe sequels – a much-needed breath of fresh air in an industry sector choked by stagnation – Smith doesn't even bat an eyelash. Things could be much, much worse, and as far as he's concerned, they're not even all that bad by any standard.

“That's such a trivial negative,” he fires back. “If I got discouraged by that, what would my father's suicide have done to me? That's hardly a blip. I'm getting to do what I am excited about. Raph and I are thrilled about this game. It's just that it's hard to do good things, by definition. There's always going to be a small subset that we consider 'good' or 'interesting,' and the bulk is going to be average.”

“But no, I don't find any of that discouraging. I wish we were all freer to do the things that we want. I wish money fell out of the sky and funded everybody's dream game. But no, it's not discouraging to me. Everywhere I look I see games I want to play. Monaco, Day Z, Red Dead Redemption, BioShock Infinite, Spelunky. In every direction there's a good game. I don't even have time to play all the good games around me right now.”

When we first began talking, I noticed that Smith reclined far back in his chair – almost like he was leaning away and attempting to disengage. But no, that's not the case at all. Smith is comfortable. He's in a good place, and he's not taking it for granted. What's done is done, and what's up next will happen when it happens. And when it does – whether it's good or bad – he'll keep moving forward. Because, after all he's seen, done, and been through, he knows he can handle it.

“People call me an optimist,” he concludes, rising from his seat. “But I do think, at a more true level, it comes from that perspective.”