What Call Of Cthulhu and The Sinking City could learn from this interactive fiction classic

Tentacles at dawn

Picture Cthulhu and his tentacled cohorts, dark and dreaming beneath the waves. H.P. Lovecraft’s crooked astral vistas - wrought out of cosmic despair, fear of the unknown, and his racism - have saturated games for better and worse. As hypnotic as his nightmare visions are, the same tropes regurgitated at face value have become dry and tired. It’s been done, and it’s steeped in its author's bigotry.

Which makes recently re-released text adventure Anchorhead a rare game: one that takes the mantle of Lovecraft and forms it into something more than the sum of its sticky, sprawling parts.

You set out to the village of Anchorhead, seeking your partner’s inevitably cursed family estate. The symbols of Lovecraftiana are wheeled out: the ivy-covered university packing Ye Olde Doom Grimoires, the furtive, fish-eyed natives, and the rising mists that whisper nightmares.

However, unlike anything in Lovecraft, you play a female protagonist. And as the Call of Cthulhu tabletop RPG dictates, you are ordinary. There’s no blasting Cthulhu (or indeed cultists) in the face. For the most part, you wield an umbrella and scraps of paper.

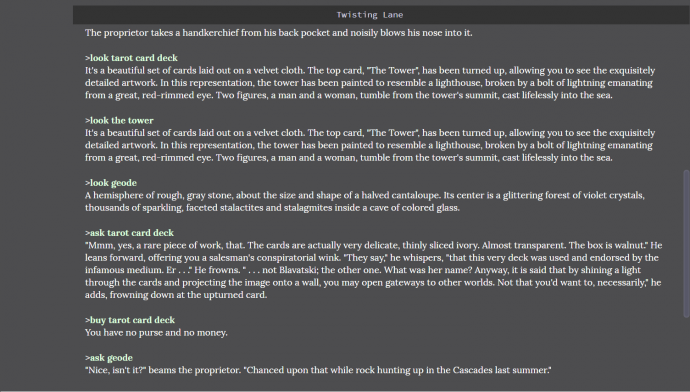

Whereas Cyanide’s recent Call of Cthulhu adaptation game is a railroad jaunt through a Lovecraft funhouse (in which choice is redundant), Anchorhead creates a place that feels real. Through words and surreal monochrome illustrations, it transports you into an open world text adventure where a myriad of fiendish outcomes await.

I drew maps to get around, learning the town’s shape, plotting routes down narrow passages from crooked houses to dirty beaches. Without this improvised map, Anchorhead will leave you adrift in a hell cycle of repeated text walls. It's old fashioned, but drew me deeper in a way that location markers can’t match.

Even better, in Anchorhead you’re not continuously mulling over your arrrrgh-so-dark past, like the predictably traumatised and unspeakably dull protagonist of Cyanide’s Call of Cthulhu. Anchorhead wheels out the usual tropes but presents them with clean, creepy and hugely evocative writing. It’s the same terror, without the reams of gruelling prose and over-the-top theatrics so common in Lovecraftian games.

Even though you go into Anchorhead likely knowing the twist (it’s all cursed and everyone’s doomed), the game still surprises. It horrifies beyond dark chanting, demented cultitsts and the big monster waiting to rise out of the ocean.

Anchorhead carves its horror out through its writing. Subtle descriptions of sound effects like whistling trains and an eerie sea make you uneasy. As time goes on, the protagonist's dreams seep a little further into their everyday reality.

There’s also an abundance of things to read and examine, and each Eldritch artefact or news report contributes to the mounting tension. Like a good dungeon master, Anchorhead reveals just enough to build a realised world, but with plenty of room for you to find your place in it.

Tonally, the game straddles a line between full-tilt and self-aware. Unlike Lovecraft’s prose, the text is not self-indulgent, even when its describing gibbering mad men and whispering obelisks. Anchorhead also has that rarest of things in the expanded Cthulhu games universe: a sense of humour.

The most cursed painting you’ve ever seen reminds you of a macabre Jethro Tull album cover. The magic shop you’ve visited to acquire your Secret Object also sells fancy new age wares, exactly the kind you’d find in a flailing seaside town. A protective necklace reminds you of those little cast pewter pieces from Monopoly. Moments like these ground the cosmic horror of Anchorhead in our reality.

To be fair, it can also be unspeakably frustrating. The puzzles in the 2018 edition were updated to be less hellish, but still operate by old-school adventure logic. Namely, your progress in averting cosmic disaster is made via rolled up newspapers, brollies, and painstaking evaluation of literally everything in the room.

By day three, death is likely. By day four, you might well die because of an item you neglected to pick up on day one. It’s a harsh, unforgiving world, and arguably winning isn't the point, but Anchorhead captures the best parts of Lovecraft through its writing. For all his arduous prose, Lovecraft’s main talent was hypnosis.

You get caught up in the dense atmosphere of his words. You listen to their eerie rhythm; weaving an uncanny dream. “I have seen the dark universe yawning,” he writes in poem Nemesis. “Where the black planets roll without aim; Where they roll in their horror unheeded, without knowledge or lustre or name.”

Like the racist edgelord himself, Anchorhead too sings that bleak siren song with its environmental descriptions, unremitting bleakness and loneliness. It can fill you with awe and longing, in the way some of Lovecraft’s tales of moon-lit towers and forgotten cities do.

It’s aspects like this that games should be adapting from Lovecraft. There is no need to explore the racism any further. Even for his time, Lovecraft’s views were considered extreme. He was fond of Hitler and penned sickening racist poetry. In the darkest recesses of his imagined worlds, dark curses are spread via inter-racial copulating.

Recent adaptations like The Sinking City can't escape this legacy, and seem unsure what to do about it. Alice B explained in her review how that game acknowledge's the original work's racism, but fails to critically engage with it. Instead it replicates them, and in some cases seems to vindicate their character's metaphorical prejudices.

We need to extract the parts of Lovecraft that are interesting, and bin the rest. Learn his spell (and that of his many contemporaries) and do something better. Most importantly, we need to actively fight the legacy of racism in Lovecraft’s work.

Anchorhead is not perfect, but it is better than most games working within Lovecraft's oeuvre. Although tales of cursed natives still feature, there are also depictions of the horror wrought on them by colonialism. Its evils are not so much the foreigner, as the evils of rich men who seek to alter reality. It’s of incest and trauma buried deep, and left to thrive - free, unchecked and swept under a veneer of propeitary.

Anchorhead shows that you can still use the tropes, and create intense horror without the nastiness.

I want more of that cosmic horror hypnosis: the dread without the bloat, as found in the blocky vistas of Doom, and the yawning black sea in Night in the Woods.

I want to see vast Lovecraft-like cosmologies. Dark Souls and Bloodborne have created gorgeous, cursed universes: where unfortunate worlds collide in fiery waltz, and hope is scraped out of a bloody void.

Games need to progress beyond recreating Lovecraft true to form, and instead continue crafting their own cosmic horror creed.