What Is The Truth About Gaming Addiction?

In response to tonight's episode of Panorama, and the accompanying discussion of the subject at the moment, I'm reprinting an article I wrote in 2007 about the subject of gaming addiction. Originally written for PC Gamer, my intention was to explore the subject from an investigative angle, rather than as an attempt to prove an agenda of either side. Sadly, I've yet to see another piece approaching the subject in the same way in the years since. In the hope of throwing out a little evidence at this time, I'm re-posting it below. Clearly this is three years out of date now. The most crucial change since it was written is Keith Bakker's complete reversal of his beliefs given at the time, now no longer recognising compulsive gaming as addiction, and no longer treating it. This change has a significant impact upon how the piece is read.

"Ready for this?" he asks, his voice speeding up. "I believe gaming is currently the greatest threat to our society."

Keith Bakker is the man behind the Smith & Jones Centre for addiction, the clinic at the centre of the current controversy over gaming addiction. It all began in July last year when the centre caught the attention of the world’s press, opening the first dedicated gaming addiction clinic, both as an out-patient programme, and then later, a residential treatment programme. Having noticed that an increasing number of their chemically addicted clients seemed to be compulsively playing games, the staff began to recognise many of the traits that indicate addiction: an inability to regulate how much time was spent playing them, continuing to play despite the negative effects on their lives, and a progressive worsening of their relationship with games.

They believed it was something very serious, and soon the clinic was taking in clients purely for their gaming habit. “A typical client would be in his late teens, he’s probably from a broken home,” says Bakker. “He doesn’t socialise, and he’s probably stopped going to school. He plays games for around 15 hours a day, and cannot regulate himself.”

So why does Britain's industry representative, ELSPA, say there's no such thing as gaming addiction? And why does Dr Richard Wood of the International Gaming Research Unit at Nottingham Trent University describe it as a "myth"? Is gaming an innocent pastime, or about to bring down civilisation as we know it? What are the responsibilities for the gaming industry? How is gaming affecting us? What is the truth about gaming addiction?

The Argument For

There are tragic stories out there. 21 year old Shawn Woolley killed himself in 2002 after prolonged stints playing EverQuest for 12 hours a day. In 2004, Zhang Xiaoyi threw himself out of a 24th floor window after 36 hours playing World of Warcraft. And the Daily Mail exploded last year with the tales of Leo Barbero, a 17 year old whose muscles had atrophied after spending 18 hours a day, once more, with WoW. These are horrific tales, inextricably linked with playing games, but are they caused by games? Were these people addicted in such a way that their fates were sealed? In other words, could we be in trouble?

"There's a lot of press that would love for me to become the anti-gaming guy," explains Keith Bakker, director of the Dutch Smith & Jones clinic. "But I'm not going to do that. As crazy as it sounds, I'm not even against drugs. I mean, if you can take drugs safely, go ahead. What I am against is addiction."

A former addict himself, Bakker was working in the music industry when he faced his own alcoholism and heroin addiction. Based in the Netherlands, he could find no abstinence-based (Twelve Step) centres in the country, and sought treatment in the UK. Determined to prevent others from having to do the same, he established the Smith & Jones Centre in Holland to offer the services he had required. He is in no doubt that gaming is addictive.

It's about an inability to self-regulate, he claims. "I'm an alcoholic, you might not be," says Bakker. "We could agree to go to a bar for a couple of drinks until 9pm. Come 9pm, you’d go home. I’d go to Mexico." It’s this lack of self-control that he says first shows problem behaviours in the gamer. "A gaming addict may sit down to play for an hour, but they won’t be able to stop. They'll play for sixteen hours, and miss school or work. But then the next time they believe they’ll be able to control themselves, and they repeat it again." He adds Einstein's words, "The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results."

Bakker is of the school of addictionologists who believe that twenty percent of people are born with a genetic predisposition to addiction. The US National Institute of Heath backs this up, their paper, "Drugs, Brains, and Behavior - The Science of Addiction," stating,

"genetic factors account for between 40 and 60 percent of a person’s vulnerability to addiction, including the effects of environment on gene expression and function."

But it shouldn't be forgotten that trauma can lead to addiction as well, points out games researcher, and self-diagnosed gaming addict, Neils Clark. "We can develop an addiction through a severe enough disturbance in our everyday lives," he goes on. "If we play in a healthy manner, and experience something along those lines, it can cause us to let our gaming fall out of balance." It’s striking to talk to Clark. As someone who cannot regulate himself when gaming, and someone who struggles as a consequence of this, it brings the subject home. People seem to be suffering.

"In high school I went to this group therapy," says Neils. "My sister had gone to rehab for heavy drug use, so I went into the therapy in order to see what she was dealing with. A lot of the people there were 50, alcoholics, meth users, previously convicts, you know. When it came time I talk about my problems, I said, 'Gee, I don't know, I think I just play games too much.' They laughed, naturally." Now he is off games, having managed to successfully play sensibly for a couple of months, until a recent collapse with a nineteen hour Civilisation binge. Clark wants people to pin down an understanding of gaming addiction. "We do need some baseline, so that we can start to help people who are flipping BMWs and jumping from buildings. We need that right now."

In his essay, Are Games Addictive: The State of Science, Clark explains, "A normal personality usually has a number of activities that they regularly use to feel excited, relaxed, or what have you. Yet people are drawn to some things over others. A huge gambling win is more attractive than cleaning a toilet. For most people. When the soon-to-be addict finds that special activity, they can have [an] 'aha' moment… At its most extreme, such a behavioural addiction dominates a person's life. They need the activity, and they'll sacrifice nearly anything – long term plans, the company of people, even work in order to have it."

The argument goes: someone who continues to play games despite these negative consequences directly affecting their life and relationships, is showing signs of addiction. Bakker, perhaps unsurprisingly, takes it one stage further. He says the addiction is a chemical one.

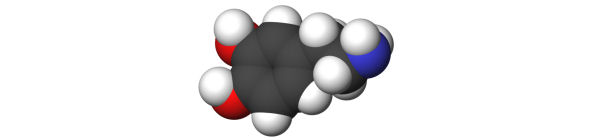

This is thanks to dopamine, the naturally occurring neurohormone released in the brain, used to fire up the pleasure and reward areas. Gaming, as anyone who has hunched over their keyboard, breath held, heart racing, will know, is stimulating. This gets our glands churning out dopamine, our neurons get wired, and we feel that rush of reward and pleasure. The argument made by both Bakker and Clark is that repeating this process enough causes our brain to become accustomed to it, which means we need to work harder to get the same level of stimulation. This, it is claimed, gives us the progressive behaviour needed for addiction. And Clark's essay observes, "When the dopamine producing behaviour is finally stopped, the brain isn't used to the lowered dopamine levels. At this point, craving and addiction enter the picture."

The Argument Against

"There is no such clinical criteria as 'video game addiction'," states Dr Richard Wood. His forthcoming paper, The Myth of Video Game "Addiction" argues, "It has not been acknowledged by any reputable organisation responsible for defining disorders of the mind or body (e.g., The American Psychiatric Association, The World Health Organisation etc.)." (It should be noted that the APA are currently investigating the topic to consider whether they will recognise it).

His analysis of the cases of claimed gaming addiction have lead him to conclude four main considerations necessary for the debate:

1. That some people are being mislabeled "addicts" by concerned parents, partners or others, when they have no problems with their game playing behaviour.

2. That some people who have other underlying problems may choose to play games to avoid dealing with those problems.

3. That some people who are concerned about their own behaviour because of either 1 or 2 above end up labeling themselves as video game "addicts."

4. That some people are not very good at managing how much time they spend playing video games.

It's by these same criteria that ELSPA, the industry representative for British gaming, deny the existence of gaming addiction. Their website, Ask About Games, was set up to answer key questions for a non-gaming audience, and at the top of its FAQ appears, "Is it possible for my child to become addicted to games?" Their answer in full:

"People play games because they enjoy them; and some people enjoy them more than others. A casual book reader will read books as part of their daily activities, and may well exercise or socialise. A person who absolutely loves books may be blinkered to everything else that goes on around them (the same goes for people who watch too many movies, or too much TV). Games playing is simply another daily activity that gives people pleasure. If they don't enjoy the games, they won't play them. If they do, they may play them occasionally, or as much as possible. Playing computer and video games is not a physical addiction."

But how does ELSPA respond to the rapidly increasing belief in gaming addiction? While no one at ELSPA was available for an interview, director general, Paul Jackson, sent us this quote:

"The primary enjoyment of computer and video games is entertainment and engagement. As with any enjoyable pastime there is an argument that you can over indulge, perhaps play too much. However, again with any enjoyable pastime, it goes without saying that those who play computer and video games – and parents who supervise their children's play – need to draw the line between healthy enjoyment and playing too much. Put simply, it is important to play for a sensible amount of time. Games as a part of a healthy lifestyle, if you like."

Once again, it comes down to self control – the very behaviour that those advocating addiction claim to be impossible for the addict. Dr Wood points out a distinction. "A young child may find it hard not to suck their thumb, many people find it difficult not to eat snacks between meals, limit the amount of coffee that they drink or the salt they put on meals." The confusion between simple negative behaviour, and that of an addict, blurs the issue claims Wood. "Some people do not want to limit or stop playing video games, even though friends or relatives are expressing concerns. Some people may also feel personally neglected as a result of a loved one's game playing. Media hype about video game 'addiction' may lead some concerned relatives to define perfectly 'normal' behaviour as problematic."

So what is "perfectly normal behaviour"? Is excessive play simply a result of irresponsibility, or poor time management. Or can it be put down to a more serious factor? While acknowledging that people may turn to excessive play as a means to deal with their problems, Wood believes that this simply a symptom of their problems, and not the cause.

"Of course some people play video games excessively," Clark explains, "but defining the point at which the behaviour becomes problematic is far from clear. If people cannot deal with their problems, and choose instead to immerse themselves in a game, then surely their gaming behaviour is actually a symptom and not the cause of their problem?"

The argument is certainly not that games are bad, from either side. Keith Bakker is quick to stress the positive sides of gaming. He explains that as a part of his programme, clients are taken paintballing. "These gamers just destroy them. We have the kids that are chemically dependent, and we have the gamers, and we put them in two teams. And at the end of the game, the chemically dependent kids – they end up looking like Rembrandt. There's so much to be said about how these kids think, so if you can take that stuff and turn it in a positive direction, you've got incredible young people. It's great fun to see these kids when they get it, when they say, 'OK, the game is killing me. And I’m not going to do it any more.' And all of a sudden they blossom, and that's fun."

Bakker's position is not entirely helped by his lapsing into the hyperbolic. Statements like his claim of gaming's danger to our society don't do anything to get those who disagree with him to listen, or take him seriously. But he's passionately convinced that gaming addiction is only treatable through complete abstinence, via a twelve-step programme; and in amongst his tendency to opt for media hype, he does have a serious point that he believes isn't being heard.

"Gamers have a unique problem. With substance addicts, they tend to develop their addiction in their late teens or early twenties. They have developed socially beforehand. With gamers, their addiction can develop as young as ten or twelve years old, meaning they never develop socially in the real world. When they are freed from their addiction, they're still not ready to reintegrate with society. When we treat them, we need a programme where we teach them new real-world ways to socialise." In other words, they aren't able to develop this self-regulation that Wood, ELSPA and others state we require.

Is this the extreme of the "geek" label? Are we, in fact, quickly dismissing those with a problem, laughingly calling them a name and leaving them to it? Or indeed laughingly calling ourselves a name, and ignoring our own situation?

New Findings

Surveys and papers are appearing increasingly rapidly, attempting to identify common factors among those who excessively game. Part of this is driven by our love of finding something to worry about, and since there's been no indication that games can give us cancer, addiction might be the next best stick to hit them with. Part of it is the fear that we might be damaging ourselves unwittingly. But despite the field being extremely new, at last some research is appearing that takes a balanced and reasoned perspective. If we're to understand where we stand with games, and whether we need to be protecting ourselves, this seems the ideal approach.

Project Massive is one of the biggest studies into online gaming and its social effects to have been carried out. The work of Ph.D. researchers A Fleming Seay and Robert E Kraut, it has followed nearly five thousand gamers over a five years, exploring their play patterns, commitment to their guilds, and changes in their personality traits such as sociability, extraversion and depression. Their [recently] published paper collating the results, Project Massive: Self-Regulation and the Problematic Use of Online Gaming, presents conclusions that, if anything, find the common ground between the opposing sides of the addiction debate.

Choosing to avoid the word "addiction" in order to escape semantic frustrations, the project uses the term "problematic use" to define a player's negative relationship with gaming, and the consequences it may have on their lives. (It is continuing despite these negative consequences that many identify as addiction). The phrase means, "the state of powerlessness a person experiences when, despite attempts to stop or reduce their usage, they are unable to walk away from a game (or substance, or behaviour) even in the face of persistent and deleterious effects on their life." The paper starts off stating their position on online gaming.

"One reason for the popularity of online games is that they meld the fun and challenge of video games with the social rewards of an online community. Participation in online communities allows us to stay in touch with old friends, meet new people, learn, and share information. It also enables self-exploration and discovery as users extend and idealize their existing personalities or try out new ways of relating to one another that can positively affect real life relationships." [Project Massive: Self-Regulation and the Problematic Use of Online Gaming page 1]

These are recognisable reasons why the MMO has become so very popular. The social side is often ignored when counting the numbers of hours people spend within a game. However, this is something else in which Bakker recognises problems. He goes so far as to compare the guilds of MMOs with cults, arguing that they share a number of similar behaviour patterns. Promotion based on increased devotion, and peer pressure to keep playing, and moreso against leaving, ensnare people, argues the maverick. ("Don't drink the Azerothian Koolaid," grins Neils Clark). Seay and Kraut, staying far more moderate than Bakker, note (from the same paper),

"Some fear that virtual communities detract from social activity and involvement in the real world, replacing real social relationships with less robust online substitutes and causing users to turn away from more traditional media."

The team were looking to see what caused problematic use, and who was most prone to struggle with it, believing that an inability to self-regulate would be the most likely indicator of those who would develop further problems. And this proved to be very much the case. People who found that they were bad at controlling the amount they played, or the appropriateness of when they played, showed, "significantly higher levels of future problematic use." From this it was concluded that,

"Clearly, the self-regulatory processes are essential in allowing online gaming to remain a benign and enjoyable pass-time rather than an obstructive pre-occupation. Active self-regulation appears to be a player's best defense."

Seay says of the results, "It is clear from my perspective that online games are intrinsically no more 'dangerous' than any other recreational activity that may require a substantial commitment of resources (e.g. time, money, attention). It is always incumbent upon the individual to manage the resources they direct toward a given pursuit, and this is no more or less true of online gaming than it is of gardening or stamp collecting." However, this doesn't make problematic use go away, and it doesn't remove responsibility from developers, she states.

"Absolutely not. No one is in a better position to help people with problematic usage issues than the developers. Successful self-regulation is based on monitoring one's own behavior and comparing that behavior to internal and external standards. If, in addition to experience points and kill counts, games made a point of reporting usage information to the player in a lightweight, non-invasive, and value neutral way, the players who most need the help would be better able to manage their own behavior. Supplying an arcane and rarely used "/played" command is not enough."

The study's conclusion appears to indicate two things: Firstly, gaming itself is not a likely cause of addiction, but rather that those who are pre-disposed to addiction are far more likely to develop problems with gaming. Secondly, that we as gamers need to be a lot more self-aware than we perhaps currently are. But in the end, "It seems safe to say that the data provide no indication that online gaming is a broadly negative activity," the paper reports. "On the contrary, the overwhelming majority of those surveyed indicate no elevation in loneliness, depression, or problematic use. This seems to indicate that, for most, online gaming is an adaptive and enjoyable, or at least benign, activity."

Conclusion

Project Massive's report finishes by identifying the importance of self-regulation. And it seems that this is the point that all come to from whichever side of the debate they may start.

Gaming, whether it's biologically addictive, a severe catalyst for problematic behaviour, or a pastime capable of inspiring dangerous levels of irresponsibility, is still hurting people. By no means everyone - Bakker notes, "Yes, there are millions of people who could really be in deep shit with this. Most aren’t." – but enough for us to start taking notice. Self-regulation - being in control of ourselves - is something that’s easy to ignore, and yet appears to be something with potentially serious consequences. It's important to remember that being carried away by a game is not the same as being out of control - a game should have us lose track of time if it's doing its job right. But when our lost time begins to hurt us, damage our lives, we owe it to ourselves to take that seriously.

Project Massive's Seay believes that responsibility can lie with those around the compulsive gamer.

"I am often asked for advice by frustrated parents in regard to children who are 'only interested in games' and 'spend hours playing like a zombie'. When asked what they should do I always give them the same answer, 'Pick up the controller.' When a parent plays video games with a child, three important things happen; the activity suddenly becomes a social one, the parent is able to model self-regulating behavior for the child, and finally, the parent is able to monitor the content of the game. All this for the low cost of spending some time with your kid doing something they are interested in."

And the same goes for adults too.

"If more girlfriends and husbands would simply engage in the activity with their loved ones it could become a unifying forum for relational exchange rather than a divisive wedge between them. If you are interested enough in the person playing the game, it seems to me you can overcome your lack of interest in the game itself."

These same ideas are echoed by ELSPA's Paul Jackson. "Parents who supervise their children’s play must do so in a responsible way and act as a modifier, as they would in any other circumstance."

When asked where he thinks responsibility lies within the gaming industry, Keith Bakker simply says, "What I appreciate is people looking at this and saying, what this can be is a problem, and if it is, you'd better get some help. But if it's not, go ahead and enjoy your game recreationally. I believe there is a responsibility to call it what it is." He is, in effect, asking the games industry to complete the first step of the Alcoholics Anonymous Twelve Step programme: admit that it has a problem. And the same responsibility falls to us as gamers. Do you?

Useful Resources

A self-diagnosed games addict himself, Clark researches gaming addiction, and writes a regularly updated blog with articles on gaming addiction written in an accessible way, even to non-gamers. He is currently writing a book on the subject, with interesting insights appearing on the site.

The home of the recently completed Ph.D. project following nearly 5000 gamers over five years, studying the effects online gaming has had on their lives.

On-line Gamers Anonymous is a twelve-step, self-help organisation, for gaming addicts. They offer support to people who believe they have a gaming addiction, or their families and friends.

Dr. Kimberly Young is the founder of the Centre for Net Addiction Recovery, and author of Caught In The Net. Her site contains information that some are using in the study of gaming addiction.

ELSPA's gaming guide for non-gamers, including concerned parents.

Independent research and consultancy services to help understand gaming behaviour.

Smith & Jones Wild Horses Center

Keith Bakker's clinic in Holland that was first to treat in-patients for what they believe to be chronic gaming addiction.