Gaming Made Me: Quake

This week, in our Gaming Made Me series, Lewis Denby explains to us how it was that Quake came to make him. In a very personal account, find out how violent videogaming took away a child's loneliness, and even got him to go to school.

Somewhere in the dusty attic of my parents’ house, there will be a box. My parents rarely throw anything away: if there’s excess clutter, the situation is analysed, and the least useful items get taken up into the loft, where they might sit for years, if not decades. Inside the box, there’ll be all manner of child’s drawings. Drawings of cars and of planes, of rollercoasters and wild animals. There’ll be the first three pages of a book called ‘The Mystery of the Lost Pin’, scrawled in a young child’s handwriting and discarded by his attention span. And there’ll be an exercise book, filled from cover to cover with level designs, monster sketches and weapon ideas. They’ll have been there since 1996, when I was eight, and they’ll all have been influenced by a single game: id Software’s seminal 3D shooter, Quake.

Quake wasn’t the first game I ever played, nor is it anywhere close to being my favourite any more. But it was the first game to capture my imagination so absolutely. I was far, far too young to be playing it, probably. I remember my mum being somewhat displeased with my dad’s decision to introduce me to it. He did, though, and the results were - I’m sure - not what either of them had expected.

I feel I should put the whole situation into a bit of context. I was an eight-year-old nerd with glasses on my face and a brace on my teeth. I was having a hard time at school. I had a few acquaintances, who were nice enough to me. I also had a group of “closer friends”, who were not. And I had a teacher so monumentally horrible, so abusive of her power over these tiny tots, that I considered her to be the biggest bully of the lot.

The result was that every morning, at around half past eight, I’d suddenly begin to feel spectacularly ill and inform my parents that I absolutely must stay at home that day. This began to happen so frequently that they were forced, on more than one occasion, to pretty much literally drag me to the door of my classroom. Things were not happy.

At that time, we’d just got our first family computer - no internet connection yet - and with it my dad had been given a copy of Quake. It had a big, fat 15 certificate on the front of the box. To begin with it was a forbidden pleasure, reserved only for the grown-ups. My dad would sneak away for an hour or so every now and then, and we’d hear muffled cursing, or the sound of a grown man jumping a foot into the air at the shock of - say - the walls dropping in Episode 1, Mission 5, revealing a Shambler, all white flesh and lightning, ready to rip his digital nose off.

I began to show an interest. And my dad began to hatch a plan.

A deal was struck. Every morning, I would get up at half past seven, as was normal. But instead of watching television, I would be allowed half an hour on Quake. This was on the agreement that, when it was time to go to school, I would do so with no fuss. I would not pretend to be ill, and I would not throw a tantrum. If there were problems at school, I would calmly tell a member of staff, and tell my parents when I got home, and they would sort it out for me.

And so, with my dad monitoring, presumably at the request of my mum, I began to play Quake. By the end of the first of four episodes, I was absolutely captivated. I had discovered 3D action gaming, and it was wonderful.

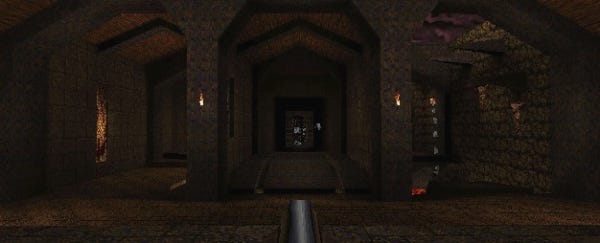

Quake is underrated. Doom gets all the plaudits for being the innovator, even though it wasn’t really, and Quake III is the title that most would point to as the pinnacle of the series, even though the first three Quake games were so different from one another that they defy reasonable comparison. When Quake gets mentioned, most people recall one of two things: that it was brown, or that it had decent multiplayer.

I wasn’t aware at the time of just how important Quake’s multiplayer was. Introducing mouselook, which very few games had implemented before, it allowed deathmatch battles to be fought at a frightening pace and with perfected accuracy. Quake also introduced the concept of the rocket jump, for which it must be commended until the end of time.

But, like I said, we didn’t have the internet. We didn’t have more than one computer to network, either. Multiplayer was a secret thing, an extra option on the menu that could never be touched. My experience of Quake at the time was single-player only. And while criticisms of the solo campaign’s dreary colour palette are kind of understandable, they tend to gloss over one absolutely crucial aspect of Quake’s design: it might have been dominated by one colour, but the variety was simply tremendous.

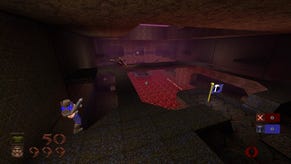

From gloomy, gothic castles to high-tech teleportation complexes, as you battled countless different foes with increasingly ludicrous weapons, Quake absolutely revelled in its refusal to stay still. Its creativity, even within the limited technical resources of the time, is extraordinary. Do you remember Wind Tunnels? The level that was split into several different areas, only accessible by allowing yourself to be sucked up by enormous vaccuum tubes? Or how about Ziggurat Vertigo, the secret level accessible from one of the game’s early areas? In that, gravity was markedly lowered, meaning you could leap around the map at will, carefully looping rockets over to the Ogre on the distant ledge.

It was this level of imagination that astounded me, and got my own creative juices flowing. Before then, my experience of games had been rubbish movie tie-in platformers on whatever the console de jour was at the time. But Quake was the real deal. You could do this stuff in computer games? Until then, I’d had no idea.

It took me several months of those half-hour sessions to complete Quake. During that time, the vague acquaintances became friends as we bonded over a new shared interest. I always assumed my dad had asked their parents’ permission before letting them play a violent videogame with me, but maybe not. Hopefully we didn’t ruin any children’s minds.

I’m reasonably sure we didn’t, though, and somewhere in that dusty attic is the evidence: sketches, idea sheets and design documents for entirely new games based on Quake’s ideas, scrawled down by a group of new-found friends, with a new-found creative hobby, in awe of the new-found imagination of computer games.