Interview: Kentucky Route Zero's Mountain Of Meanings

Kentucky Fried Chattin', Pt 1

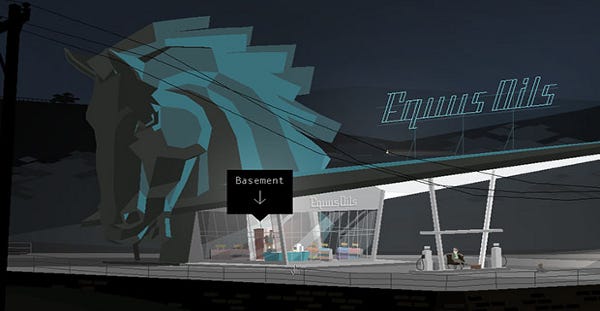

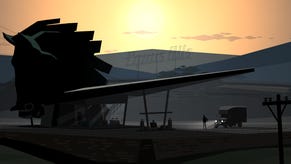

Kentucky Route Zero is a joyously original, heartfelt thing. If you haven't already played it, go do that. If you have, then step on down to the RPS porch, pull up a slightly weather-worn deck chair, and let some soulful bluegrass overwhelm your senses. Easy, easy. The interview will begin soon, but for now, there's certainly no rush. Oh, fair warning: it's pretty SPOILERY. Co-creator Jake Elliott and I discuss Kentucky Route Zero's unique approaches to storytelling, theater's heavy influence on the game, the negative general perception of the American South, talking to animals, ghost stories, economic hardship, and a number of specific in-game scenes. So then, stroll on inside RPS' quaintly rustic hilltop abode whenever you're ready. Or don't. There's always time.

RPS: What influenced Kentucky Route Zero? Especially on a personal level, where did the game come from?

Jake Elliott: My girlfriend’s from Kentucky. We have family there. We go down there quite a lot. I was down there just driving around, thinking about this video game idea that I had that was about. First it was about a giant who would carry people around on his shoulders. I guess it just transformed along with the landscape, looking at trucks shipping stuff around, going to antique stores and stuff. Before that, also, Tamas and I worked on a game with our friend Jon Cates that he concepted out. It was this art game. It was never really released publicly, but it was in a couple of gallery exhibitions. It was more of a gallery installation kind of context. You know this game Colossal Cave Adventure, by Will Crowther?

RPS: Yeah, totally.

Jake Elliott: A text adventure. This was a remix of that game using some source material from the original game and then a bunch of stuff that we wrote. It was kind of a cross between that game and Being John Malkovich. It’s this idea of Will Crowther during the time in his life that he was writing this game. It was this weird, surreal biography game. That game takes place in Mammoth Cave in Kentucky.

Tamas and I got really into thinking about Mammoth Cave and stuff. That colored my trips down to Kentucky. I came up with this thumbnail sketch of the game and brought it back to Tamas. Then, after working on it for about a year, we started feeling out more of what were some other directions we could go with it.

Something that we stumbled across then was this interesting relationship equivalence between set design in theater, like stage theater, and video game work. We were making these little scenes in Unity, these little 3D scenes, and setting up props and stuff with a whole lot of consideration for the angle the player was going to be looking in from. They started to really look like theater sets. Then we started looking at modern American mid-century theater, and looking specifically at set designers. We found a few set designers that we really liked. That theatrical influence started to really transform the game, and moved it away from being what it was originally, which was a kind of exploratory platformer that was not challenge-oriented, but more about climbing around in the caves. That pushed it more towards this dramatic, more theatrical kind of game that was totally character-driven.

RPS: Now that you mention it, that does make a lot of sense. I felt a lot like I was putting on a performance whenever I was playing it. Almost like the bits where I could pick dialogue were improv. I could add a little bit to Conway based on what I wanted to bring to him, but my choices didn't change the overall plot progression.

Jake Elliott: Yeah, totally. We’re thinking of it like the way that an actor chooses… They don’t necessarily choose the dialogue or the plot, but they choose how to inflect it and how to think about, depending on their method of acting, the inner life of the character. There’s a lot of construction that happens, creative construction that happens at the level of the actor in a play. We’re trying to put the player in that role.

RPS: Right. And on the whole, a lot of the games that get made these days are still very influenced primarily by other games - or, failing that, literary greats like Transformers and GI Joe. It seems like you plucked influences from all over.

Jake Elliott: Yeah, I think that’s true. For Tamas and I both, making games is something that… I’ve been doing it for about four or five years, and Tamas for a couple of years. But our background is more in the art world and noise music and performance art and stuff like that. There’s a lot of other influences that we’re drawing from. I think also, a lot of games, especially some of the more big-budget games, draw a lot of their influence from cinema. We’ve been looking at theater as opposed to cinema.

RPS: So I really liked interacting with the dog, Blue. I’ve decided that is her name, because that’s the choice I made, and the other choices are wrong.

Jake Elliott: I’m feeling good about the way that people are responding to that. It was a really late addition, actually. We just added it as a detail, and it started to seem like a really compelling element in the game. I’m glad you felt attached [laughs].

RPS: You’re not going to pull the Fable thing, are you, and kill the dog at the end?

Jake Elliott: Oh god, I haven’t played Fable. Did they kill the dog at the end?

RPS: Yeah, in the second one.

Jake Elliott: That’s terrible.

RPS: It’s kind of brilliant how they do it, though - even if it's kinda emotionally manipulative. They have that happen, and then the final choice at the end has you choose between saving thousands of people or bringing back your dog. There’s maybe one other choice. I was like, “Fuck, man, the dog. Duh. I don’t even know these people.”

Jake Elliott: It’s also in Shadow of the Colossus. You form this relationship with your horse. Or in Red Dead Redemption also. You feel attachment to these horses. People can form attachments to animals in video games really closely.

RPS: Whenever I’m at home alone or something, I’ll totally do that with any animals that are around. I’ll say stuff to them, which is weird to tell people, but everyone does it. And yeah, so I was always really compelled to tell Blue what I had done while I was away.

Jake Elliott: Yeah. It’s an opportunity for a monologue, for him to just speak his mind. In most parts, we’re trying to be really naturalistic about the dialogue. There’s a little bit less exposition there than I might want to insert if I were writing another kind of script. The dog works really well for that, too, to give the player a chance to recap or to exposit some of the inner life of Conway, the character.

RPS: Kentucky Route Zero definitely feels more literary than a lot of games, more focused on things that I think are traditionally the domain of literature. In fact, it struck me as almost poetic, again, insofar as it was just there. Instead of saying, “Here’s this overarching message that I want you to take away from this,” it was more like just, “Experience it and derive your own conclusions.” Is that what you wanted the game to do? Do you have an underlying reading you really want people to agree with? Or are you hoping for more of an open dialogue?

Jake Elliott: It’s somewhere in between. I think for both of us, both in the art and the writing, we have a pretty… I guess I could call it a postmodern, bricolage kind of process, where we’re drawing in a lot of different stuff. There’s a lot of different ideas working in parallel in the game. We’re packing it full of a lot of these different references – literary references or visual references, references to other video games.

We do have what would be a story bible in this case. It has a few thematic threads that we are referring to and trying to work in at different places. It’s organized on that level. But it’s not a unified thing. Maybe it’s all pointing in the same direction in terms of tone, but there are a few ideas in it that are definitely going in different directions.

I guess at the core of it, it’s about different ways that people deal with hard times, and the different ways that economic downturns affect people who live at the margins, who are disempowered, and how they make use of those situations or how they deal with those situations. And also this idea of debt is a really central theme of it. How do people get into debt? What impacts does it have on their life?

RPS: What made you want to engage that subject matter with a game, of all things?

Jake Elliott: I feel totally suffused in it. It’s like the air that I breathe right now. It’s happening for everybody. Everybody that I encounter, all of the time. It’s just part of the world that we’re living in right now.

I think that a game is a good way to engage it, because… One important thing about understanding the effects that things like austerity and economic downturns have on people is understanding that it has different effects on different people. Being able to empathize with different people and hear the effects that it’s having. Games are really good, or can be really good, at provoking empathy or supporting empathy. That made it seem like a good medium, to me, within a character-driven game, to work through that issue a little bit.

RPS: I think that was my favorite thing about the dialogue choices. It was always some variety of characters dealing with a crummy situation. It was just different ways of dealing with it - never anyone suddenly taking superheroic, Commander-Shepard-like action or going totally out of character. I sort of ended up playing Conway as trying to be tough or trying to play things off like they weren't as big of a deal as they actually were.

Jake Elliott: Right, yeah.

RPS: You pose this as a ghost story, which is pretty neat. I think there are a lot of things that bill themselves as ghost stories, but don’t really get the vibe of it. Whenever I was playing Kentucky Route Zero, I never felt overtly threatened by anything, but there was always this vague sense of foreboding and mystery. There was this world that I was not really in control of, which is very different from other games, where it’s all about the player having power.

Jake Elliott: Yeah. It’s not a game about people who are in power. It’s definitely a game about people who have been disempowered by circumstances.

RPS: Yeah, absolutely. Why did you decide to position it as a ghost story, of all things?

Jake Elliott: I don’t want to go too far forward, because there’s still some thematic stuff that needs to come out in the later acts, but there’s this thing about ghosts where they’re trapped, you know? Trapped on earth. There’s a sort of metaphoric thing that we’re going to push down there about people being trapped.

Also, one of the big sources of inspiration we were drawing from is the culture of Kentucky itself. Bluegrass music. Which is mostly based on hymns. It’s mostly these folk arrangements of hymns. Most of the hymns are about death, which is so weird. Death, either the fear of death and the fear of god or death as a relief because you don’t have to work anymore. There’s a lot of death hanging in the culture of Kentucky. Ghosts are a sort of personification of death, or something like that.

RPS: How many Kentuckian things did you specifically research? Was it more just like by being there you picked up these things by osmosis, or were you like, “I want to learn more about this subject and that subject and that subject”?

Jake Elliott: A lot of the stuff that’s on the overworld map is based on real locations. Just twisted in some direction or another. There’s the bait shop in the overworld. That’s a specific bait shop that I photographed somewhere. Tamas goes through there a lot also. He has family in Missouri and in Kansas. He goes through Louisville a lot. He also looked a lot at the landscape and reproducing the landscape in a specific way. There are certain trees. There are certain kinds of rolling hills and stuff like that. I think those are the two places that it comes up, the original research in Kentucky.

Also, I did the sound design. We have a composer who we work with, Ben Babbitt, but the environmental sounds were mostly me and Tamas. We tried to keep that stuff, the sounds of the birds and crickets. We tried to keep that to being real wildlife from the region. It wasn’t always. There are a few of those environmental backing tracks of owls and stuff that are from, like, Holland [laughs]. But mostly we tried to keep them in that area, Kentucky and Tennessee.

RPS: Another thing I noticed that made me feel like I was in Kentucky or a place like it was the way that a lot of characters were really open and jovial in their speech. In a lot of games, it doesn’t really make sense to me. I’ll go up to a character in an RPG and they’ll tell me their life story for no apparent reason. But in KRZ, it feels like kind of a Southern thing, I think, to be that way. “Hey, welcome to my home. Come on down, ya'll. I’m gonna talk about things now.”

Jake Elliott: Yeah, yeah, definitely. There’s a sense also that it’s nighttime, or it’s evening at first. There’s not a lot of pressing stuff to be done. People are taking their time, you know? It sets a pace for the game, too. There’s not so much urgency. The slow pace was really important to us.

RPS: It’s also interesting, because I think right now there’s a kind of societal tendency to portray the American South as a really backward and awful place - both socially and politically.

Jake Elliott: Yeah, there has been for a long time.

RPS: But I think especially in the wake of the recent elections and whatnot, whenever things are really divided. And it's really easy to demonize people like that based on media coverage and whatnot. But I actually come from Texas, and - for the most part - it's home to some of the nicest, most accepting people I've ever met.

Jake Elliott: Especially in video games, too, there’s a lot of hillbillies. I mean, there’s not a lot of them, but when there’s people from the South, they’re usually hillbillies. We’ve been thinking about that from the start, about these stereotypes and stuff.

Another big source for us, particularly in the writing, has been Southern Gothic fiction, like Tennessee Williams, Flannery O’Connor, and William Faulkner. A lot of that writing is in response to prejudices against people from the South in that era, from the ‘30s to the ‘50s or so. The characters in a Faulkner book are often pretty grotesque. They’re often pretty dark characters. But they’re very complex and well-realized characters. They’re not grotesque because they’re stupid. They’re grotesque because they don’t have the fear of God, or something like that [laughs]. They’re grotesque for other reasons.

RPS: Are you worried at all that a large number of your players might not get those references, though? Or do you think you stand to get more people interested in this kind of literature?

Jake Elliott: One thing about that is that the audience for video games is really growing. The group of people who are making games is really expanding and diversifying. If you look at stuff like the popularity of Twine for making games, you can see that there are all of these new game developers who are not coming from a background of being gamers, and who are not coming from any place anywhere near the game industry. They’re bringing in people who would not have thought they would like a video game, but they know this person from some other context or they know the context that this person is dealing with. I think there’s more people playing games now who might be interested in some of these literary themes and stuff, or who would know where it’s coming from.

RPS: You mentioned Twine, which has been a really cool thing to watch people embrace so much. Kentucky Route Zero had little areas that were small text adventures. How much do you keep up with that whole scene, though? Were those sections in KRZ an intentional homage to that, or was it a more practical concern - like, “Well, I don’t really have the time or money to make full environments for this, so let’s do something smaller-scale.”

Jake Elliott: I follow that scene really closely. It’s probably the part of the spectrum of games that I follow the most closely at this point. It was definitely deliberate. I am excited about these games that people are making in this form. I wanted to play with that form, so that’s where those little side areas come from. I remember hypertext being… Especially in the ‘90s, there were all these interesting hypertext stories, and then it sort of fell out of fashion. It’s cool to see that this tool has reinvigorated people’s interest in that. I like the scale of Twine games a lot, how short most of them are and how free and expressive most of them are.

I really like Merritt Kopas. She has a couple of games, or several games. There’s one called Brace. It’s a two-player Twine game. You and the other player take turns covering your eyes. Then it tells you when to tap the other player to have them move in. It switches perspectives between these two creatures. You’re getting different parts of the story and interacting with each other. It’s really cool.

Check back tomorrow for part two, in which we discuss Kentucky Route Zero Act II, bluegrass music, using Kickstarter before it was cool, The Walking Dead, and a secret from Act I that kind of blew my mind. OK, totally blew my mind.