What Lies Ahead For Kentucky Route Zero

Kentucky Fried Chattin', Pt 2

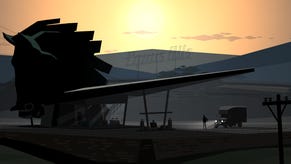

Yesterday, we began our journey down the winding highway that runs through Kentucky Route Zero co-creator Jake Elliott's brain, and today, we'll resume it. But while looking back is all well and good (especially on brain highways, where traffic's fierce and blind spots can hide unspeakable dangers), doing it at the expense of moving forward is unwise. So now it's time to delve into what's next: the release schedule for the rest of KRZ's Acts, how our choices will carry over, The Walking Dead's influence on the process, and a fairly mindblowing portion of Act I you probably missed. Don't worry, though. It wasn't your fault.

RPS: There was a really great bit in Act I where I was in control of both parts of a conversation between Conway and Shannon at once. That was super bizarre and jarring. Where'd it come from? Will we see more of it in later Acts?

Jake Elliott: We’re going to kind of push that in some other directions in the later acts. That was basically Tamas’s idea. It came, actually, from… If you look in the trailer for the game, there’s a different view of when Conway and Shannon meet each other. It’s looking out of this cave and the camera kind of turns. That is not in the game.

That was the original version of that scene. I guess Tamas, based on the way that scene started, with this nice camera turn revealing Conway, he just put the little interaction box above him. It was more of a visual decision than anything. He said, “Oh, maybe that would make sense. We could switch perspectives there for a little bit.” It came from a weird angle, and then we just started pushing it from different directions. Then the dog thing came after that, too. Having a monologue. Then there’s a later conversation that takes it in a different direction.

RPS: Speaking of future episodes, will any of the choices I made come back in a significant way or progression-altering way? Like, there was the phone call Shannon was having when I first met her, and I only saw one side of it? Will I eventually see the other?

Jake Elliott: Yeah, that one will come up again. We store, in the saved game file, a lot of different decisions that the player makes. Our goal is to bring them back up in ways that are more poetic rather than being big branching decisions. We have plans for a few of them to have some kind of weird consequences. Small things that you do that you don’t expect to have large consequences. It’s not supposed to be a place where the player is being strategic. It’s supposed to just be something that’s responding to what the player does. Does that make sense?

RPS: Yeah, absolutely. That sort of tends to be the issue with a lot of choices in games like that. If it’s strategic, then people sort of boil it down to a min-maxing thing. “If I make this choice, my curly mustache of pure evil will swell with new abilities.”

Jake Elliott: Yeah, like in those BioWare games. You always want to push the morality bar to one extreme or another, to get certain powers. You end up saying these things in dialogue where it’s like, "I don’t really feel like saying that, but I gotta push that evil meter."

RPS: In the second episode, could I just suddenly play Conway a very different way? How would that affect the overall flow of the game, especially with it storing up reactions to the different choices I made?

Jake Elliott: I think it’ll be still pretty open. There are a few moments when you have some options about specific things related to his background that act like permanent choices, though. There’s a part where you can talk all about his parents. That locks off other choices later, because now you’ve made a decision about who his parents were.

I think there’s still a lot of flexibility, though. It’s not super permanent or super finely detailed, the characterization, in that way. Although I guess it probably is in the player’s head, which is where it’s important anyway. More important than this XML file where we store this stuff [laughs].

RPS: How much is set in stone for the acts overall? You’re doing them episodically. Now that you have the first one out, are you planning to be a bit more reactive with the other ones based on what people say, or is it more like you have a plan and you’re going to stick to it regardless of feedback?

Jake Elliott: It’s really not so much reactive to people’s responses to it, or reactions to it, as it is to just where Tamas and I are at when we’re working on it. We have a schematic. We have an outline for each act, the code is all there, and the workflows are all there. Whereas a year ago it could have gone in a lot of different directions, now the the code and everything is all pointing to this one set of interactions, which you’ve seen in the first episode. That stuff is not really going to change.

As for the plot, it’s important to us to at least to keep the major plot points the same, so we have the ability to do foreshadowing and keep things thematically consistent as we go. But also, over working on the game for about two years, Tamas and I developed a sort of comfort and confidence in being really organic about it and making big changes. Trusting each other to make big changes and also trusting ourselves to make big changes when they feel right. That’s the nice thing about doing it episodically like this. We can get it to start to be a real thing – to feel real, to be a thing that people really play – but also keep some of the spontaneity of it as we work out the rest of it. Which would have been hard if we had done the whole thing before releasing it at all.

RPS: Was there ever a point when you were making Kentucky Route Zero where you considered taking a more puzzle-heavy, er, route?

Jake Elliott: Yeah. We play a lot of those games, those point-and-click adventure games, so it’s in our heads. Pretty often we find ourselves sketching out [puzzle ideas]. Like the mine sequence. When we first concepted that out it was a big puzzle. It was a big maze and then there were all these things you had to turn off and on to make your way through it.

It’s just a habitual thing. When we find ourselves doing it, we move away from it. “That’s a puzzle. Let’s not do that.” One reason is that I’m not really… Maybe Tamas is better at this than I am, but I’m not very good at designing puzzles. I’m not really clever that way [laughs]. A couple of the first games that I made were puzzle games, and they were not very good. I never really honed that skill or was interested in doing it.

The one puzzle that we did, if you could call it a puzzle, is in the very beginning, when you go down into the basement. That started out even more puzzle-y. We had a lot of alpha testers and beta testers, but nobody could get past it. It was adventure game logic. It was totally opaque. It was originally this really weird thing where you had to go into this one corner of the basement and turn the light on and off three times. There were these cues in the environment to indicate this to you, but it was really esoteric.

That was actually a good reminder to us that we’re not good at designing puzzles. They don’t add much to the game anyway. I think a lot of the time puzzles in adventure games end up just gating content. They slow the speed at which you get to the good stuff, you know? It’s a thing that we do. Climax denial? I don’t know what to call this thing we do. But it’s in all kinds of contexts.

RPS: Certainly. I think one thing Kentucky Route Zero did really well, though, is that it still had a build-up to it. It didn’t just hand everything over right away. But it was more because you slowed the pace. There was the one bit close to the end of the first Act where, after all the mine stuff and Conway’s leg got messed up, I had to walk up the hill again. It’s really slow, which is what you’d expect, because his leg isn’t working right. But that scene… It gave me a lot of time to just take in the environment, where I'd been, and what brought me back to that point.

Jake Elliott: Yeah, I like how that worked out. The first time you go through that scene, you see him running up. The image in your mind of him running up the hill re-emphasizes how slow he is now and how damaged he is. Definitely, the pacing thing is [important]. Although parts of it I think we made a little too slow. The last update that we released speeds up the tram in the mines [laughs]. That was a little too slow.

RPS: You worked with a real, live bluegrass band! Why that one? And how?

Jake Elliott: I went to school with the guy, Ben Babbitt, who’s the composer. He’s a friend of ours. He works with a lot of musicians who are in this sort of folk, weird folk music community. There’s a lot of interchange or exchange between Chicago and Louisville of people doing this kind of weird folk music. [Ben] brought a couple of his friends together to make the band, the Bedquilt Ramblers. It isn’t like a real band, beyond the name. This is the only thing that they’ve done. One of those folks, Emily Cross, is the woman who’s singing and playing guitar sometimes. Her music is really awesome. It’s also on that edge between folk music and weirdo electronic music. It’s really cool. That’s how we hooked up with them.

We had these six bluegrass songs that we picked out from old hymns and bluegrass standards that had themes that were on our minds when we were designing the game. We asked them to record those songs, and then also to write these ambient electronic pieces that were in the same key as the songs, so we could fade back and forth between them. We had this idea that the band was going to be present in a scene. As you approached the band it would turn more to bluegrass, and as you moved away from them it would turn more to this ambient music.

It totally didn’t happen at all. We didn’t do that at all [laughs]. But the songs that they composed are tuned to the bluegrass songs in a weird way. Hopefully that does something to the player’s ear. There’s some remnant of that decision.

RPS: Yeah, there was the one scene where the band was there, present, on the edge of the scene itself. Why did you choose to put them right there? It definitely created a really cool, mood-shifting effect, but what was the purpose behind it?

Jake Elliott: Part of that placement is also about this thing in theater, especially in classic Greek theater, about the chorus, you know? You have this space where they’re up in front of the stage and they address the audience directly. These people in the band kind of function like a chorus in the game. It’s kind of hard to tell in Act One, but they’re actually the same people as are in the basement at the beginning.

RPS: Whoa, really?

Jake Elliott: It’s a little bit hard to tell, but if you look at their outlines closely, you can tell. Also, the instruments are leaning up against the wall in the basement. They’re supposed to be addressing the audience in a way. That’ll probably be easier to read later. That’s one place we might react, to the fact that nobody picked up on that very well. We’ll have to make that clear.

RPS: I think I'm actually legally obligated to discuss The Walking Dead at this point in the interview, given that we're talking about an episodic game series. How much of your decision to do that was about keeping an ongoing, TV-season-style discussion surrounding your game, ala what Walking Dead has done?

Jake Elliott: Not much, actually. We were looking more, as weird as it might seem, at a game like Minecraft or Prison Architect, where they have this rolling alpha release that people can buy in on early and then get updates. We were excited about the possibility of, like I said earlier, getting the game to be a real thing that’s in the real world early on in the process, relatively. Just psychologically, the game is not really real until people are playing it. That can be quite a large psychological weight. It’s also helpful for us to have to have a cutoff point. “We can’t add anything more in Act One right now.”

I think we really did benefit a lot from the timing with The Walking Dead having just wrapped up when we released our game, though. That game opened a lot of people up to episodic gaming, but also to the idea of this character-driven gaming that wasn’t really [challenge-focused]. Walking Dead has puzzles, but they’re not hard.

I think that people are more receptive to that, having seen it play out with a story that they were interested in anyway because they liked The Walking Dead. We used that as a point of reference. When people are like, “So, what’s the game like?” we could say, “It’s kinda like The Walking Dead.” That’s been helpful for us, also, giving us a way to explain ourselves.

RPS: “It’s exactly like The Walking Dead, only we have ghosts instead of zombies.” Speaking of, what's your plan for releasing the rest of the episodes? Do you have a general timeframe for each of them, or is it just going to be when they’re ready?

Jake Elliott: We have a time frame. We’re trying to get the last one out a year after the first one came out, so January 2014. That gives us three months for each Act. We looked back at how long things took us, and that seems like about the right amount of time to get the amount of content that we’re trying to do in there.

We spent the last two years immersed in this workflow, and it’s like the only thing I know how to do right now [laughs]. Making Kentucky Route Zero. It feels good, the timeframe feels good. We’ll probably announce release dates as they get closer, but yeah, roughly three months for each one.

RPS: So March or April for the second one?

Jake Elliott: Yeah, something like that.

RPS: Good. You should release it on my birthday. Thank you for your time.