Wot I Think: Portal 2

Portal 2 has now unlocked. If you've preloaded it, you should be able to start the unlocking process now. I played the game all the way through last week, both single-player and co-op, and am very pleased to tell you, without a single spoiler, Wot I Think.

Here’s a thing I feel safe to say: Portal 2 is Valve’s first full-length single-player game since Half-Life 2 in 2004.

For everything else, I’m in a pickle. And if you want to enjoy this stunning game properly, you should be concerned too – if you’re planning to read lots of reviews of the game before you play it, I beg you to be careful. The biggest dilemma in front of me now is how to tell you why Portal 2 is quite so magnificent, without robbing you of any of the surprises I received when playing. And the frustration is, you won’t understand why I can’t tell you things until you’ve played it for yourself. After about the first hour, everything in Portal 2 is a spoiler. Even the co-op. I’m going to try to review it for you now without ruining anything.

Um.

It’s really bloody good.

Let me see what else…

So what do you already know? From the comics we know that Chell is once again the protagonist, dragged away from her seeming victory at the end of Portal, imprisoned and once more awakened in a mysterious chamber. We also know, by her all-encompassing presence (if you’re in America, she’s on TV every five minutes, on every bus, on every poster) that GLaDOS is, by some means, returning. Despite her quite substantial destruction.

And you’ve probably heard that there’s a new character voiced by Stephen Merchant, Wheatley. You know that Aperture boss Cave Johnson is involved in some way. You’ve seen that alongside the portal gun there’s now paint-like gel with special properties, and t-beams which can carry objects. Have you seen the bridges? There are bridges too.

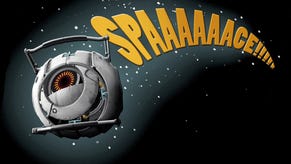

Test subjects are woken from their enforced comas every few years, medical reasons, and so it is that Chell is awoken in a run-down, faded, eroding room by the frantic knocking on the door. It’s Wheatley, one of GLaDOS’s former personality cores, desperate to get your attention. He’s to be your guide, an occasional companion as you explore the derelict remains of the testing facilities, now overgrown with plants.

Things begin in a familiar way, reintroducing the basics of portal dissemination, first with only one portal, then two, in puzzles that are different but reminiscent of the opening of the first game. It’s of course necessary, because that special place your mind goes into to be able to “think with portals”, as Valve so aptly describe it, needs to be reawakened.

But it’s far more involved than just that. Aperture is in a terrible state, ruined, after hundreds of years of neglect. Wheatley’s guidance is peculiar, with his mostly being stuck on rails, and means your path is an unusual one. The elevators aren’t all working, so you’ll be sneaking through panels and dropping in to familiar but disheveled rooms from new entrances.

And all the way you’re being entertained by a breathtakingly good performance from Stephen Merchant as Wheatley. Ricky Gervais’s frequent comedy partner firmly establishes himself independently here, offering a naturalistic delivery that hits every beat with exquisitely effortless timing. It’s often hard to follow his instructions, because you know that if you wait Wheatley will make another joke about it. Merchant has recorded so many alternative lines that it takes far longer than most will be willing to hang around before you’ll hear him repeat.

Along the way you re-encounter GLaDOS. How – I’m not going to say, because it’s a wonderful moment. What happens as a consequence – I’m not going to say. Where you go next – I’m not going to say. You can see the issue.

In many ways, this opening act feels like a deconstruction of the original Portal. Smart writing and smarter puzzles cunningly reference what you already know, but require more inventiveness. The behind-the-scenes view of familiar-but-derelict test chambers feel like a breaking of the frame from the off, in a way the first game offered in its final third.

The game’s in three acts, and it’s not a fraction of an exaggeration to say that telling you even the most basic details of the second part would absolutely destroy some surprises that brought me much joy. I want you to have them too. So dodging around this, I’ll say that the paints you’ve likely seen in the trailers make their appearance in this second section, and I want to relieve some of the fears you may have about them.

When I first saw that this new element was being included in screenshots I feared this was going to be an example of sequel feature overloading, where a developer becomes afraid their follow-up is too similar to the original, so stuffs it full of new content that removes the previously engaging simplicity. That simply isn’t the case here.

The gel was appropriately inspired by a project by students at DigiPen – the same institute that provided us with the student team that went on to head up the development of Portal. Members of Tag: The Power of Paint’s creative team were hired by Valve, and concepts brought into the new game. But rather than adding a paint gun, or complicating your interaction, instead these new tricks are all intelligently implemented via the portal-based techniques that already make sense.

Blue paint on a surface creates a bouncy pad, that will launch you the same height you fell onto it from. Orange paint lets you move much more quickly, which opens up lots of inventive uses for portal physics, especially in the co-op game. And white paint added to a surface makes it possible to place a portal. The extraordinary liquid physics make it a mad pleasure to splatter paint around levels, and the feeling of adapting your environment can create the sense that you’re being much more inventive in your puzzle solving. Especially when you’re redirecting the paint from its sources using portals.

However, gel also causes my most serious criticism of the game. One of the key pleasures of Portal is that sense that you’re inventing the solution to a puzzle, whether it’s one of many or the only possible route through the level. Occasionally with the paint it becomes too obvious that there’s really only one way to complete a room, and you’re not going to do it until you’ve stumbled upon the logic they used. One level in particular requires the exact placing of paint in heavily prescribed places or it’s simply impossible. I’m certain some of my plans should have worked, but fell fractions short of success in a way that didn’t feel entirely fair. While there’s a sense of satisfaction in eventually realising the solution, it’s preceded by a good degree of frustration that never appeared in the original game, and thankfully only occasionally appears in the sequel.

The mistake, I think, is in having you fall just short of your target platform in these circumstances. It suggests that you mistimed your jump, or didn’t fall into a portal from quite high enough, and you can find yourself repeating the same futile route again and again until you give up and try something else. This, combined with a brief failing of Valve's trademark semi-conscious signposting of what you should be doing next (which is blissfully brilliant elsewhere in the game), leads to a brief sag.

However, that’s not true of so much else. Another sequel fear I had was that it might get too difficult. That’s not realised either. It’s definitely more difficult than Portal, but only in a way that continues the smooth curve established by the first game. Where Portal 1’s most complex challenges tended to involve finding ways to fall a long way into a portal, to fire yourself out of another, Portal 2 seems to knowingly mock you by preventing your doing this. So often you’ll see a gap and a drop and you’ll think, “I know what to do.” But then you’ll see they’ve deliberately made that route unavailable, forcing you to reimagine. GLaDOS is messing with you.

Also new, and absolutely always brilliantly included, are the T-Beams and hard-light bridges. The former are swirling tunnels of energy through which both you an objects can float. The latter are thin sheets of a blue “solid” that can be walked on. And both can pass through portals opening up a kajillion new puzzle solutions. Just think about the possibilities for a beam through which you can float a cube, dropping it from one to another by redirecting an exit portal to elsewhere in a room, then floating yourself along the beam through a portal to reach another area. It requires you open more doors in your brain, to think in even more dimensions.

There’s also a few new blocks, the most significant of which is one that can redirect red laser beams, which again expands the puzzling possibilities. And never more so than in the co-op.

Here again I bang up against the wall of spoilers. I literally cannot tell you the context for the co-op without ruining the end of the single player game. What I can say is make sure you finish the single player before you start the co-op, as it references much that came before, as well as assumes a lot of knowledge about how gel, beams and bridges work.

However, what is safe to say is quite what a significant difference there is when buddying alongside a chum. The first few levels are expertly designed to force your brain into thinking in yet another new way. This time it’s how you approach a level with the availability of two pairs of portals.

Both players can pass through the portals of the other, so here the challenges can be far more elaborate. Where once you were limited to propelling yourself in only one direction, here you can be flung all over in fantastically complex manoeuvres. There’s also some awesome new tricks available, such as one player putting two portals on the floor and ceiling, and then the other player falling through them to reach enormous speeds. At this point the first player can switch the exit portal to somewhere else in the chamber sending their buddy flying incredible distances. Stuff you simply couldn’t do on your own.

Co-op has its own narrative, although not one as compelling as the single-player’s fantastic story. Here it’s much more about mind games between the two players, which is a lovely angle. However, the significance of its ending seems far more loaded than anything else in the game – big consequences. I’d also argue that it could be interpreted as an origin story for Valve Software, although I’m not sure that’s their intention. You’ll see what I mean. We'll write much more about the co-op soon.

Most of all, Portal 2 is funny. It’s so damned funny. It’s funny from the opening scene (“When you hear the buzzer, stare at the art.”) to the very final moment, which made me guffaw. Gags in the opening sequence with your introduction to Wheatley play on how games work, memories of the original game, and whole new running jokes that are surely to become the next wave of memes.

And splendidly, the game does not rely on referencing the original. Cake goes almost entirely unmentioned, and it’s certainly not about being a lie. And your cuboid friend? Well, no way am I going to take anything away from that. But again, just brilliant.

And praising Merchant as I have above cannot stand alone. Ellen McLain returns as GLaDOS, and is pushed so much further this time, hitting every single line with perfection. The volume of incredible jokes is beyond belief, each tinged with a slithery cruelty that makes it almost hurt. J K Simmons is also fantastic as Cave Johnson, really throwing himself into the role with spectacular gusto. It's an all-round remarkable cast, delivering some of the finest writing video gaming has seen.

Improvements to the Source engine are abundantly clear when compared to the original Portal. The titular holes are more beautiful, and the locations so elaborately detailed and animated.

Gosh, the animation. Panels are not just a joke for the trailers. The walls of test chambers being made of hundreds of panels on robot arms is absolutely key to the entire game, both in terms of how it’s approached, and its narrative. Rooms can be adjusted mid-flow, the walls, floors and ceilings seemingly alive.

The detail kept taking my breath away. At one point there’s a walkway to run down, on your way to the next location. You’re running past some machinery that’s used to construct turrets, just backgrounds. But I stopped to watch through one window, crouching to see past a rail, and saw the most extraordinarily elaborate, Pixar-like detailed sequence of about eight robot arms meticulously building a turret from scratch. It must have taken someone days to put this animation together, and it’s completely throwaway, in the corner of your eye, designed to be run straight past. That’s the level of detail going on in this remarkable game.

Wheatley also deserves special mention. Those personality cores you saw gibbering at the end of Portal 1 had some character. But the animation in Wheatley’s is utterly beyond belief – what is essentially an eye somehow manages to communicate shame, fear, guilt, happiness, cheekiness, and so on. It’s an incredible feat.

There’s also a great deal to find for the more careful player. Littered with Easter eggs, they’re often far more involved than the hidden rooms found in the first game. There are at least two entire songs to be discovered by those willing to explore, as well as many more snippets of story if you meddle with objects and the environment beyond the main demands.

Alongside that, there’s an entire other story going on if you’re looking for it. If you’ve seen that episode of Community where Abed has the relationship with the pregnant girl, you’ll know the sort of delivery I mean. A whole other story, separate from that of Chell, Wheatley and GLaDOS, taking place out of focus in the background, with a wonderful pay-off in the closing sequence.

Coulton’s new song is as good as Still Alive – which is no mean feat. The National’s song is so amazingly nonchalantly included that I didn’t even realise I’d found it at first. And most of all, everything is so, so funny. It’s undeniably one of the funniest games of all time. I laughed out loud so often I began to feel self-conscious.

And crucially, when I’d finished the game, both single player and co-op, the first thing I wanted to do was start again. So I did.

There's so much more I want to tell you! I want to tell you about the [REDACTED] turrets that [REDACTED] creates. I want to tell you about the sequences in the [REDACTED] from the [REDACTED]. Gosh, I want to tell you about the bit at the end with the actual [REDACTED]. I want to explain the whole potato thing to you! I think if I did I'd write something that better conveyed the exciting reasons to play. But something that would make playing far less exciting. Apart from that brief saggy moment toward the end of the second act, this is a refined, ludicrously detailed, and wonderfully smart game. At around eight hours long for the single player, it's also nearly three times longer than the original, with another six or so hours for the co-op. Of course you should get it. In fact, you should have been reading this while your pre-load was unlocking.