Wot I Think: Quadrilateral Cowboy

Stylish enough to forgive its flaws

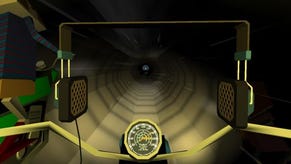

I've lined up my suitcase rifle, sawed open my escape route, and written two lines of code to control a small robot when I blink. Blink once and a set of lasers turn off allowing me to enter through a space station maintenance tunnel without triggering any alarms; blink twice and a second set turn off, allowing me to exit cleanly. It's only a few moments later, as I stand in the vacuum of space, that I realise I left my deck - the computer by which I write scripts to control suitcase rifles, small robots, lasers and more - back in the maintenance corridor.

Quadrilateral Cowboy is a game about breaking into buildings to raid vaults, steal safes and hack coma patients. It's a stylish, retro-futurist love letter to computing, engineering and '90s videogame level design. It also feels like the prelude to a better game.

It starts well. Technically, you are not carrying out heists, but planning them. You and your two partners-in-crime have built detailed 3D worlds of your target buildings, which you then enter to complete your task virtually as practice for the eventual mission, which happens off-screen. This justifies a great many things, including simple greybox level design that removes the visual clutter between you and your goal; patch notes floating in the air containing subtle hints among the changelogs; and the ability to press F1 at any point to switch into 'noclip' mode in order to explore a level fully before you set your plan in motion.

The main affordance of this fictional trick is your deck, the tool by which you interact with the world. Set down this computer on any surface and you can then control its simple DOS-style interface with your keyboard, typing short commands like "door2.open(3)" to open door 2 for 3 seconds. Eventually you start stringing together those short commands like "jump; datajack; datajack 0" in order to, all at once, tell a small robotic dog to jump forward, plug itself into a 'datajack' socket, and perform that datajack's first action - which is, just as often, opening a door for three seconds.

Don't fret if coding isn't your thing. The commands are never more complicated than those above and the game introduces you to new commands at a leisurely pace. In fact, almost every level of the game is designed to introduce you to something new.

After becoming familiar with using the deck to directly interact with the environment, you're introduced to that small robotic dog I keep mentioning. Her size can access areas you can't, so you can direct her using your deck to control machinery from greater distances. After becoming familiar with the dog for a mission or two, she's forgotten. You're introduced to the suitcase rifle, which you aim and fire with the deck. Once you feel comfortable with it, using it to fire bullets into buttons not people, its usefulness diminishes. Instead, here comes the Launcher, which is like a Quake 3 jump-pad where you can control the pitch of where it tosses you.

Next you're given the ability to enter heists as different people with different abilities, and to put those abilities to use simultaneously. You'll enter a level as one person, place a launcher, hop across a large gap, and use a tool to jack open a door for 60 seconds; then you'll hop out and re-enter the level from the beginning as the greaser, who can jump high and squeeze through small spaces. You steer them to follow the ghost of your first character, enter that now open door and clear the next set of obstacles. This feels like the game's ultimate form, where your complete toolset allows for the clockwork precision of an Ocean's Eleven caper.

Which makes it strange that the game then abandons even this concept after two missions, piling all those abilities into a single character. After two further heists that make use of all your tools simultaneously and which, finally, seem to allow for some creativity, the game is over.

It's not that the game feels too short. It's that it feels like a succession of tutorials leading up to a game that then lasts for just a few missions. None of the tools you're introduced to feel as if they're used to their full potential. You're given a chance to get used to them and then the game moves on. This may be because those tools don't have a great deal of potential: whether writing scripts on your deck, steering your robot towards datajacks, or deploying doorjaws, powersaws, or your rifle, all you're ever doing is opening a door.

Unlike other reach-the-door puzzlers such as Portal, there's no moment where the level design combines with your earned understanding of the tools to enable thrilling ingenuity; unlike other similar heist-'em-ups such as Gunpoint, there's no comic consequences to experimentation. My experience was of muddling through the game's four-hour length and never being wholly satisfied by my solutions, but while others may find it compelling to polish performances in order to beat friend's completion times, I don't find that motivating enough to want to play missions a second time.

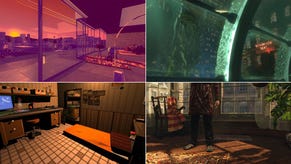

Yet despite my criticisms, I do think it's worth muddling through those missions at least once, simply to bask in its style. Quadrilateral Cowboy is created by Blendo Games, whose previous games include Gravity Bone and Thirty Flights of Loving. Many of those games' flourishes return here, from the full-screen title cards introducing each mission, to between-heist vignettes which wordlessly advance the story via smash cuts and rooftop badminton matches.

There's also an affection for old technology that I find wholly charming. Where background details might be drawn with simple, flat-textured blocks, machinery is often rendered with multiple moving parts. Your first task at your headquarters is to build the computer with which you're going to simulate each heist, individually slotting in first the CPU, then the heatsink, then the memory and so on. At any point during each mission you can put some music on by popping a vinyl record in your portable player. You hack those coma patient's brains with a device that sounds like an old dial-up modem. The books at your base have titles which each convey parts of the compile process for an old-fashioned first-person shooter level, from BSP to VIS to RAD.

Few games are ever truly made by a single person, and there are other names in the credits, but Quadrilateral Cowboy feels like a singular vision. It's what happens when someone is allowed to develop a personal voice, from Quake 2 mods through to (Doom 3 engine powered!) commercial releases. It is delightful enough that I can forgive the hollowness of its core challenge.

Less easy to forgive are its bugs. I experienced six or seven crashes to desktop while playing, and multiple occasions during which my view, controls or deck became stuck and required a mission restart. I rarely lost much more than a few minutes progress, but when that progress involved fiddly setup and scripting, that was a few minutes too many.

In 2011, when describing why Introversion had abandoned Subversion, their long-in-development heist game, designer Chris Delay described a problem with the genre: "In the end, after all that development and years of work, you still completed the bank heist by walking up to the first door, cracking it with a pin cracker tool, then walking into the vault and stealing the money. There was no other way to complete that level. And this would be the essential method by which you would complete every level after that."

It feels as if Quadrilateral Cowboy never finds a solution to this problem, but it moves through different ideas quickly enough, and does enough with its cool, colourful world and story of silent friendship, that I enjoyed my time with it.

Quadrilateral Cowboy is out now on Windows via Steam and Humble for £15/$20/€20.