Wot I Think: Virginia

Twin Piqued

I’m delighted to say that Virginia [official site] was not at all about what I thought it would be, what it seemed to be. Pretty early on, its narrative took a surprising sideways step, a sudden and yet fluid motion that made it feel fresh, exciting and unpredictable. It was the first of a series of such steps the game would take, crabbing its way into increasingly unusual territory until, at the end of its two hour story, I wasn’t quite sure where either of us were left standing. Many of its surprises were pleasant, but others were perplexing.

Ostensibly, Virginia is about two women working for the FBI in the early 1990s, tasked to find a boy who has gone missing in the titular state. However, this missing person case isn’t quite what it seems. Nor is your own objective. Nor even is your character or, it seems, much of what’s going on around you. By its conclusion, I wasn’t entirely sure what Virginia was about and I’m not sure how much of this I could attribute to imperfect storytelling, to elements of very deliberate obfuscation or to my own ignorance. Virginia is strange and fascinating. It definitely isn’t for everyone, but it certainly is remarkable.

It’s unapologetically linear throughout. If there are many opportunities to make choices or control the narrative, I didn’t find them and most of the time, I was exploring static environments or clicking the mouse to advance the action. In an RPS interview two years ago, developer Variable State unabashedly owned the often disparagingly-used term “walking simulator” and that should give you a firm idea of what you can and cannot expect from it. Your role is to watch, to search, to prompt and, occasionally, to discover.

Oh, and to interpret. If you’re anything like me, you’ll frequently be trying to interpret much of what you see. Good luck with that.

If you’ve not caught any of the the previous coverage of the game, then there’s something you need to know: Virginia’s narrative is neither linear nor reliable. Like one of its key inspirations, Thirty Flights of Loving, it skips from scene to scene, from location to location, sometimes without warning, but it also jumps between the past and the present. It also plays coy games with you, bouncing you between the real and the unreal, between dreams, visions and the everyday. Occasionally these scene changes are linked by the same objects, symbols or motifs, other times they might be simple match cuts, at other times they’re an outright surprise.

This all happens in a stylised world that isn’t quite cartoonish but has something of a pastel, sometimes almost watercolour feel to it. It’s populated by a blinking, frowning and scowling cast who emote almost melodramatically at times, yet are also just as likely to remain inscrutable. Nobody in Virginia has anything to say. The game has absolutely no dialogue and only small amounts of text. It spends most of its time talking to you through its extensive and often impressive orchestral score, the emotional anchor of the game and far less ambiguous, rising and falling as it carries you from moment to moment.

And many of those moments are now lodged in my recent memory: the exploration of a deserted observatory; a strange midnight encounter; an apparent out-of-body experience. I want to avoid specifics because there’s so much in Virginia that is very, very easy to spoil and I think that ruining what is coming could dramatically colour your interpretations of what you see. Like the game’s characters, I want to remain mute.

But there are some themes that are blatant. The game’s opening, for example, is an overtly feminine-coded moment, placing you opposite your reflection and directing you, with your very first action, to apply your lipstick. It’s a first scene that’s simultaneously going to be mundane for so many, yet alien to others, and which is so very rarely portrayed in video games. It is a simple, unambiguous opening statement made from the tiniest action: you are a woman.

You are a woman of colour, too, as is the partner that you will soon meet. In the FBI of the early 90s, you are not about to have an easy time. There are many incidents that I couldn’t help but second-guess because of this. Does my identity explain the silent stare of a colleague, the disrespect of a man, the over-familiarity of a stranger? Or am I reading into things that aren’t there? I think these are questions Virginia very much wants me to ask (giving me, a man, the luxury of experiencing my uncertainty in this safe, virtual context for one brief evening), all the while peppering me with subliminal suggestions found in location and character names like Tubman, Sojourner’s Truth and even Halperin. I found myself questioning some of these apparently mundane incidents almost as much as the increasingly bizarre imagery and confusing, fractured narrative.

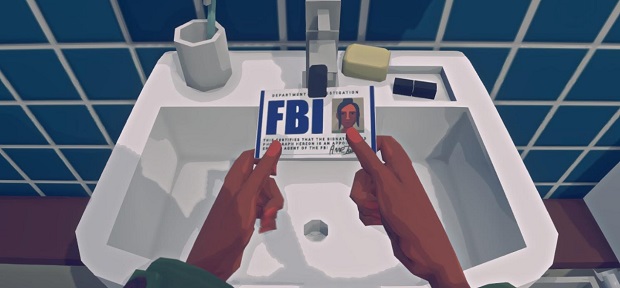

I’m sure you can tell that I frequently found Virginia compelling. But it can also be frustrating or overly simplistic. It’s narrative can be heavy handed, with occasional unnecessary flashbacks reinforcing moments you already knew were significant, and the camera is overly keen on forcibly taking control, repeatedly directing your gaze. At one point, I thought I was waiting for a scene change, not realising I had to click the mouse to perform the relatively impotent, insignificant gesture of showing somebody my FBI badge. It’s not always clear when you should move on and when you should linger, or even sometimes exactly what has caused a plot development.

Similarly, you can wander through areas you might expect to be full of clues or detail, only to find them mostly void or absent of anything to do. Virginia can do a good job of demonstrating how a space tells you about a person, tells a story, or gives up some tiny secret, but it only does this sometimes. Not all of its locations feel as rich or as lived in as those of Gone Home or Firewatch. Alongside its peers, I was reminded most of Dear Esther: I keep moving forward, I’m not supposed to stop, take in the view or smell the flowers. Even when the game does want you to take a moment to search around, there’s usually only one undisguised, plainly telegraphed thing to find.

And like Dear Esther, I think what Variable State are aiming at here is something that connects more emotionally than intellectually. This is a story painted with strong, broad and deliberately incomplete strokes. It most certainly is not for everyone, but it has no such ambition. I think the best thing about Virginia is that it is unashamedly being what it wants to be. It will connect with you best if you’re the kind of person willing to meet it in the middle. Though a Lynch comparison is overly, overly simplistic, if you enjoyed trying to figure out what Mulholland Drive was all about, I think you’ll enjoy this. Conversely, if you didn’t, I’m quite sure you won’t.

I’ve played through Virginia twice. The second time through I found I was still just as frustrated both by unnecessary prompts to move the action forward, as well as by renewed searches of certain locations in the hope I’d missed something. Mostly I hadn’t, save a few cosmetic items to collect for achievements, yet several of those achievements remain locked and I can’t conceive of what else it is I might need to do. Or to see. I suppose that’s yet another part of this mystery still to be solved, though how big or significant a part I have no idea.

It’s not because of these achievements that I feel ever so slightly unfulfilled. It’s because I want just a little more from Virginia and yet, like its characters, it mutely refuses to deliver. I think it’s a strangely touching game, evocative and effusive, but it’s also not as subtle as it may think it is. It’s occasionally plodding. Its cast would benefit from being more naturalistic. Nevertheless, even a second time around, I couldn’t quite decipher its remarkable closing acts, which bewildered and beguiled me. The soundtrack (all courtesy of a real orchestra) is strong, vibrant and expressive. The story and its telling are both quite singular, if sometimes lacking in clarity. At the cost of player agency, it’s the most cinematic game of its sort I’ve played, far more so than Thirty Flights, and the cinema it reminds me of is Lost Highway or, yes, Mulholland Drive. A note from the creators says they hope they have made a game that is “strange and confounding.” That is certainly, definitely, absolutely true.

So, do you want to try a game that is “strange and confounding”? If it was up to me, everyone would play this. Then they would tell me not just what they thought of it, but what a certain item, location or actor signified, because an important part of Virginia may well be what you bring to it. I know many won’t like the idea of traipsing through its scenes or passively watching its unfoldings and, sure, if you think you won’t enjoy any of that, you’re right on the money. But if you’re a little bit curious, or if you enjoyed any of the games with which it shares its DNA, Virginia may be one of the oddest and most fascinating things you’ve played in a long, long time. Vivid Virginia is a hell of a lot more than plain old “walking.”

Virginia is available later today, for Windows and Mac, and can be bought through Steam. The demo is available now.