Wot I Think - Total War: Three Kingdoms

Where Total War meets Crusader Kings

My eldest son died horribly at the Battle of Yangzhou in 198 CE. Cao Ang led a small retinue in General Xiahou Yuan’s army. Xiahou’s army was the best I had: disciplined troops, carefully selected and commanded by heroes. At Yangzhou they were mauled by a massive army of peasant rebels led by the Yellow Turban He Yi. My defeated army escaped, but He Yi challenged Cao Ang to a duel and personally killed my son. Though my son was not a great commander or, obviously, duelist, his death is a tragedy for my whole faction. Cao Ang commanded a third of the defeated army, and without a substitute general his retinue will disband. The only candidate has no military experience and has never left court: Lady Bian, the boy's mother. She assumes command in tragic, desperate circumstances; in 201 CE she will march back to Yangzhou to duel the rebel who killed her son and become my greatest general.

Total War: Three Kingdoms is a historical strategy game set during China's Three Kingdoms period. The campaign is divided into two layers: players build towns, recruit soldiers, declare war and move armies across a map of China each turn. When two opposing armies fight, players command units in real time. You're a warlord in a shattered kingdom, and every campaign begins with the same instruction: China must be united.

Three Kingdoms is the best historical strategy game in a very long series, and certainly the most dramatic and personal.

Family members die, generals defect, courtiers hate one another, and the daughter you married to an allied warlord will reappear in a decade as an enemy general. For those experienced with Total War, the most disorienting changes in Three Kingdoms will be the intense focus on individuals above states or armies. In earlier Total War games you were Rome, France or Oda depending on the game’s time period and geographic span. In Three Kingdoms you’re Cao Cao, Liu Bei, Yuan Shao or another individual in ancient China. You've got armies and generals and territories, but they won't protect you from a cavalry charge.

This shift from the player as a state to the player as an individual character is possible because Three Kingdoms has shifted Total War's focus away from history and towards romance. The game is as much an adaption of the fourteenth century novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms as an attempt to recreate China as it existed in the second and third centuries. The closest comparison might be if a Total War set in sixth century England had King Arthur, Mordred and Excalibur. The individuals in Three Kingdoms are real, but I'm pretty sure Liu Bei couldn't single-handedly kill 90 archers.

Three Kingdoms begins in 190 CE with Han China collapsing and the infant emperor imprisoned by the tyrant Dong Zhou. Dong Zhou is the common enemy of all the playable warlords and the closest Total War has come to introducing a villain. Dong is easily the strongest, richest, largest power and peaceful coexistence with him is all but impossible due to his toxic combination of traits: arrogant, vengeful, tyrant and destructive. A few of the implications of these traits include his inability to join existing alliances, preference for the most destructive option for captured soldiers or settlements, and my favourite, tyrant, which the game describes as: ‘Terrorises others by constant war threats and punishes whoever opposes him.’ The best method for avoiding war with Dong Zhou is to be very far away from him.

In my first campaign as Cao Cao I begin the game at war with Dong Zhou, and my single town is surrounded and facing an army led by Yuan Huan of the Han Empire. Total War battles are initially intimidating: each side fields up to eighteen units (plus reinforcements) and before you can attack you’ve got to deploy your army. This is easier in practice than theory: Three Kingdoms positions troops sensibly by default even when an army is badly composed, and it includes a menu of prebuilt formations along with explanations for when each should be used. I deploy my cavalry on the wings with spearmen beside them, swordsmen in the middle with Cao Cao and missile units in front of the army so they can fire an opening salvo: it turns out some strategies are timeless, or only time-sensitive to the widespread adoption of gunpowder.

Total War is, of course, a long-running series and previous entries have covered periods from ancient Rome to feudal Japan. I beat Yuan Huan with a strategy I have used across literally thousands of years: draw the infantry into mine, swing the cavalry around to beat his archers and then send the cavalry into the back of his infantry line. Perhaps the most surprising thing about Three Kingdoms is that winning battles in China the same way I have won battles in the Mediterranean, Japan and Central America doesn’t feel horrible.

Three Kingdoms’ AI armies are extremely predictable. In most other strategy games they would be infuriating. However, in a series which resembles historical war more closely than most others it’s difficult to say where strategy ends and exploit begins. Commanders really have made stupid decisions about deployment and tactics in our world, and in Three Kingdoms the distinction between the ‘decisions’ of a character like Yuan Huan and the failure of the game are very unclear. For what it’s worth, I was winning evenly matched battles at the hardest difficulty in the game’s custom battle mode, and there was no great difference in the capacity of the battle AI to make good decisions regardless of difficulty. Three Kingdoms can be hard, but its difficulty comes from the campaign, which rightly places you against stronger factions and armies such as Dong Zhou’s.

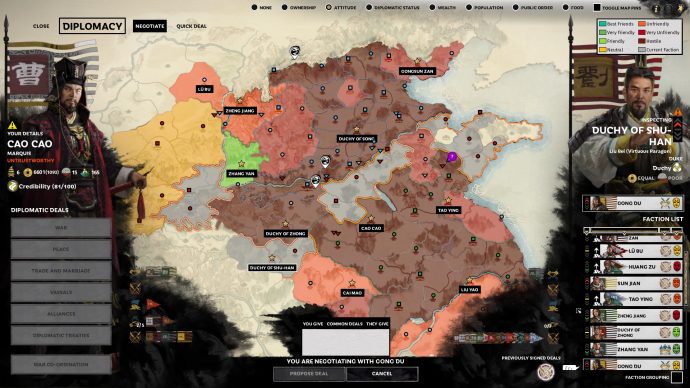

On the diplomacy screen the register of factions Dong Zhou is at war with is a stack of more than fifteen flags. A shared enemy is often the best way to make friends, and in the early years of the game my best friend is my neighbour to the southwest, Kong Zhou. While I conquer Dong’s temporarily weak subjects, Kong stays at home and strikes trade agreements.

Kong is too pure for a series called Total War. Every faction leader in Three Kingdoms has a personality, derived from their traits, which determines their behaviour as an AI. For Cao Cao it’s Strategic Mastermind, for Dong Zhou it’s Cruel Tyrant, and for Kong Zhou it’s Peaceful. Peaceful characters have no wish to expand or maintain armies and always avoid conflict, which is just great in a game about war. It’s surprising his faction lasts eight years and is destroyed by Yellow Turbans rather than Dong Zhou.

Yellow Turbans are rebel armies that roam around the map, often without territory of their own, attacking weak armies and looting weak settlements. Kong Zhou lasts one turn against them when the roaming army crosses Yangzhou, conquers Kong’s territory and destroys his faction. I’m also at war with the Yellow Turbans, who are suddenly on my border and they’re led by the ferocious general He Yi, who is a level above even Cao Cao. Xiahou Yuan, my most successful general that year, races south to stop them capturing my territory too, and to even the odds I add my eldest son to his army.

As I mentioned, Three Kingdoms has an extremely strong focus on individual heroes and their relationships to one another. One way in which this manifests is retinues, which means that though one character commands an army, each character is directly attached to a retinue of up to only six units. Xiahou Yuan leads the army, but his retinue is just two units of cavalry, two units of spearmen and swordsmen and archers. His army also includes Cao Ren, my cousin, whose retinue is composed of axemen, archers and sabre cavalry. Cao Ang joins the army not because he’s personally essential to victory, but because without him an army with a maximum of twelve units would be facing He Yi’s army of eighteen units, since he’s got sub-commanders too.

There isn’t time to recruit units which would take my army to its maximum possible size, nor to wait for Cao Ang’s retinue to be fully reinforced: in any event, it’s not why I lose the battle.

Unlike previous Total War games, generals aren’t joined to a bodyguard unit and they can be commanded as individuals. Heroes like Xiahou Yuan, Cao Ang and, obviously, He Yi can be incredibly strong in battle. When they engage enemies at the right time in the right way they can be terrifying: in one battle Cao Ang’s successor Lady Bian will personally kill 176 enemy troops, which makes her either a legend or a monster. He Yi is the strongest hero I’d faced so far, and I was cautious of his potentially devastating impact on my troops, so I make a fatal mistake and have Cao Ang challenge him to a duel.

Duels are a wonderful addition to Three Kingdoms, and to the Total War series. They complement the thematic shift towards individual heroes over anonymous armies, they create interesting decisions and, obviously, they look amazing. Cao Ang and He Yi ride across the battlefield, attempting to knock one another off horseback. It’s difficult to overstate how great it looks when the armies are slowly advancing towards each other and two horsemen shoot out of their respective lines, battling with arrows flying overhead, cavalry charging passed and fleeing units breaking apart around the duel. Total War games have been beautiful for some time, but its focus has always been on battles at the scale of armies, and it’s baffling how good one-on-one combat looks, particularly since the inventory of each general - the type of weapon they use, the horse they ride and the armour they wear - is visually represented. Characters occasionally clip through one another, but in screenshots and from a bird’s eye distance it’s flawless. I’m excited to see what better video makers and screenshot-capturers than myself can create.

Though Cao Ang is weaker than He Yi, their relative strength before the duel showed He Yi as ‘negligible,’ possibly because Cao Ang’s class, Champion, specialises in duelling.

This is no comfort when Cao Ang is swiftly killed before he can even retreat and admit defeat. The participants in duels have health bars visible across the map, but because there’s so much to manage in Three Kingdoms’ battles, it’s possible to miss your general’s own diminishing health until he’s been knocked from his horse and died among his men. I’m still unsure if the estimate of the power balance between the two characters was displayed incorrectly, or if Cao Ang got very, very unlucky. In any event, his death ended a battle which was already trending towards defeat. All units in Three Kingdoms have morale, which when broken makes them flee, and I gravely underestimated the tenacity of peasant militias.

As I mentioned, I replaced the dead Cao Ang with his mother and Cao Cao’s wife, Lady Bian, because she was the only character available. Without a hero to lead them, retinues dissolve. Lady Bian was initially useful to ensure the size of the army didn’t drop by a third. The army had time to rebuild and, in fact, grow greater than its original size because the Yellow Turbans were busy fighting another army which invaded them from the north. We’re all rebels in Three Kingdoms, but the Yellow Turbans are probably the closest to revolutionaries, and they’re hated by almost every faction as a result. It is in 201 CE, after they defeat the northern army, that I attack a severely diminished army of Yellow Turbans. Lady Bian has her first heroic moment when she kills one of the Yellow Turbans sub-commanders: like her son, she’s a Champion and specialises duels with other leaders.

Lady Bian’s career is in many ways the career of my entire faction. Cao Cao commands his own army, of course, but he stays in the north to watch my increasingly scary coalition partner Yuan Shao who, after Dong Zhou is killed by his son, becomes the next threatening thing. Cao Cao fights alongside Yuan Shao against Dong Zhou, but once he vassalizes the tyrant’s son and becomes the terrifyingly powerful Duchy of Song, the alliance is more about beating my ally to enemy settlements and capturing them first than any real cooperation. In the south, Lady Bian fights a shifting collection of factions whose alliances swap turn-by-turn. Tao Ying is my enemy, then he’s the vassal of my ally. Liu Yao is my enemy, only he joins the coalition of Sun Jian and drags them to war with me, then leaves the coalition and makes peace - except I’m still at war with his former friends. I didn’t record the year, but at some point the whole army comes to be led by Lady Bian with Xiahou Yuan and Cao Ren as her sub-commanders. I’m not sure why they swapped, but by then Lady Bian has the best stats and highest level of the three generals thanks to her habit of killing enemy heroes in single combat.

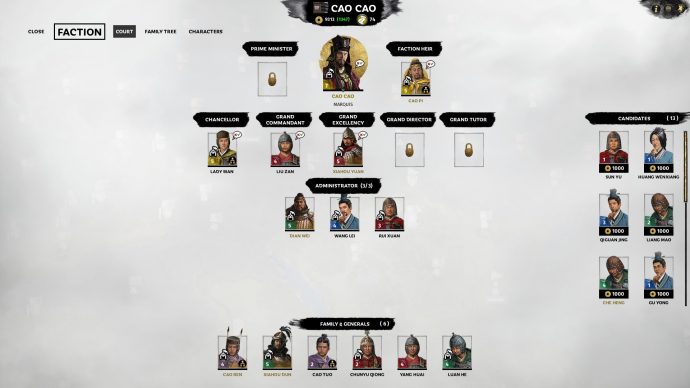

Lady Bian has a tense relationship with her sub-commanders. Every character in Three Kingdoms has an attitude to the others they work with which is determined partially by compatible or incompatible traits and partially by past experience. Bian, Xiahou and Cao have been fighting together for a long time, so they have positive opinions of one another, but only Xiahou and Cao have compatible traits. Lady Bian has many of the same problems at court: among the characters who have a position, she gets along really well with her husband, Cao Cao, and terribly with her second son and the faction heir Cao Pi.

Lady Bian’s army wins so often I’ve never had to break it up, but characters with low opinions of one another can spark civil war if they’re left long enough. I had to break Cao Cao and one of his most capable generals into separate armies for exactly this reason. Lady Bian and Cao Cao are both suspicious, and both have intelligent traits. As factions grow, vacant court positions multiply. When Cao Cao ascends to the rank of duke there are two clear factions in court: Cao Cao, Lady Bian and Grand Commandant Liu Zan tend towards diplomacy and espionage, whereas Xiahou Yuan, who occupies the office of Grand Excellency, gets along with Cao Pi because they share zealous, honourable and dutiful traits. The disagreements never provoke a civil war, but in appointing new ministers I consider their match of traits with each side.

Lady Bian’s greatest victory, in fact, comes as a result of this complex relationship system. Three Kingdoms has limited espionage which allows players to hire their heroes out to other factions. When my ally Yuan Shao’s faction evolves into the Duchy of Song I send an idle hero, Zhao Du, into his court where he is appointed a general. Having spies provides greater intel on your enemies, and I was pretty sure the only way Cao Cao would become emperor was by destroying the Duchy of Song. Except within a few turns I received the extremely troubling report that Zhao Du genuinely swapped sides to the Duchy of Song.

When I eventually fought Yuan Shao, the greatest threat was two massive armies invading from the north east, across the Yellow River. One of those armies employed Zhao Du as a commander. At the Battle of Yangye, Lady Bian fought both armies alongside her own army and reinforcements from a nearby town. Both sides had in excess of 2,900 soldiers, and it was the largest battle of the whole campaign. The game predicted my side would suffer a valiant defeat.

I emerged with a victory - albeit having lost 2,384 men, two more men than my opponent’s 2,382 - and two captured generals, one of whom is Zhao Du. Players have three choices with captured heroes: employ, release or execute. Employ swaps disaffected characters to your side for a price, release lets you demand a ransom, and execute allows you to seize an item from their inventory. The other captured commander is executed because I want his special breastplate, Champion’s Leather, which I give it to Lady Bian. I don’t want Zhao Du’s item - a carved wooden pig - but I execute him anyway. There is something about his dialogue when I hover over the execute option: ‘I served you loyally… You wouldn’t kill me would you?’ Delivered after actually losing a battle to the faction of which he’s supposed to be a member, it’s infuriating enough to warrant the death penalty.

I don’t win the war against Yuan Shao but Lady Bian and Cao Cao combine to make it only a partial loss. Lady Bian’s greatest contribution is actually capturing the emperor alive. Though all the factions in Three Kingdoms compete to become emperor, the Han Empire is still in merely terminal decline in 190 CE. At the beginning of the game it is a vassal of Dong Zhou, who is the Prime Minister of the Han Empire because he holds the infant emperor hostage. Should you take the emperor hostage yourself, by kidnapping him from the faction capital by siege or assault, the Han Empire territories swap sides and become a vassal of yours. Unfortunately by the time Lady Bian does this, the Han Empire - which begins the game rich and with lots of territory - has declined in value.

Cao Cao’s contribution was to bring a third party into the war. Each faction in Three Kingdoms has a unique resource which allows them to take unique actions or gain bonuses. For Cao Cao, that’s Legitimacy which builds at a rate of two per turn to a maximum of 100. At the cost of 75 Legitimacy, I had him initiate a proxy war between Yuan Shao and his hated western neighbour Gong Du. Cao Cao can’t force allies or truly unwilling sides to battle, but Yuan Shao was so ready to go to war with Gong Du he actually paid me to drag him into it. Without this war, I would’ve faced the whole of the Duchy of Song alone and likely been wiped out.

Much of the joy of future games of Three Kingdoms will come from experimenting with the unique resources of other factions. I briefly tried the Bandit Queen Zheng Jiang, whose unique resource makes her stronger when she causes chaos, encouraging players to sack and withdraw from enemy cities rather than occupy them. There is, obviously, a lot more to do.

If you haven’t played a Total War game before, I should also say that Three Kingdoms is the best possible start. It’s great, but it’s also the clearest game in the series. Both the campaign and battle layers make what is happening on-screen much more apparent than previous Total War games. The need to have a wiki open to remember exactly how food works or which troop should be engaging another has finally been exorcised from a series that desperately needed a refresh of this scale. When you select a unit in battle, dangerous enemy units are marked with an alert, and when you select an enemy unit you can see at a glance which of your units can beat them. On the campaign map the tooltips are the best they’ve ever been and the map itself is visually much clearer than its predecessors, owing to its more abstract, watercolour style.

I have found very little to complain about in Three Kingdoms itself, least of all the amount of content. The differences between the factions is far more significant than in previous Total War games (excluding Total War: Warhammer) and it’s easy to imagine my campaign playing very differently if Cao Cao had died in 198, or if the tensions between my generals ever erupted into civil war. I have had no technical issues with Three Kingdoms either, but given the released state of previous games in the series people will be rightly cautious about buying Three Kingdoms as soon as it’s available. It is, however, a shame that playing as the fascinating Yellow Turbans requires pre-ordering the game or buying it in its first week. I doubly hate that you can view their three leaders in their own tab on the faction select screen even if you don’t own the DLC: please just show me the content I can actually use, Three Kingdoms.

Three Kingdoms is an absolutely massive game, but it has a very clear thematic focus on the Three Kingdoms period - specifically the Romance of the Three Kingdoms - and a very clear mechanical focus on individual heroes. The shift bears an obvious resemblance to Crusader Kings II, which uses the lives of individual characters to liven up a game which might otherwise be stuffy. Indeed, Three Kingdoms defuses the impersonal, often boring expansion of empire which has plagued previous games in the series like Rome II with a riveting web of friendships, rivalries and grudge matches. Despite the resemblance, there really is no game which has quite the same combination of elements, nor is there any strategy game that looks this good. Defending a town in the evening light, watching your troops wade through shallow water and sending opposing lines crashing together is a spectacle. It’s the best Total War game, the best historical strategy game released so far this year, and its stories are so compelling I’m as excited to read about other people’s anecdotes as I am to create more of my own.