Wot I Think: Ape Out

Current trends say apes are in, actually

Once I went to the zoo in San Diego, and a load of people were banging on the glass at an orangutan and its baby instead of just being appropriately (quietly) awed. One man in particular was hollering at what was a very sad looking ape, and honestly if there was justice in the world the orangutan would have smashed free and liquified that man’s limbs like a bouncer squeezing an uncooked sausage. In Ape Out, there is that justice. And jazz. And it is glorious.

Ape Out is a top down action game and, like an all weather wood sealant, does exactly what it says on the tin. You play an ape (a gorilla, specifically) who has been unjustly confined, and must change your status from ape =/= out to ape = very much out indeed. This is achieved by employing the two biggest, strongest weapons that nature has bestowed on you i.e. these hands.

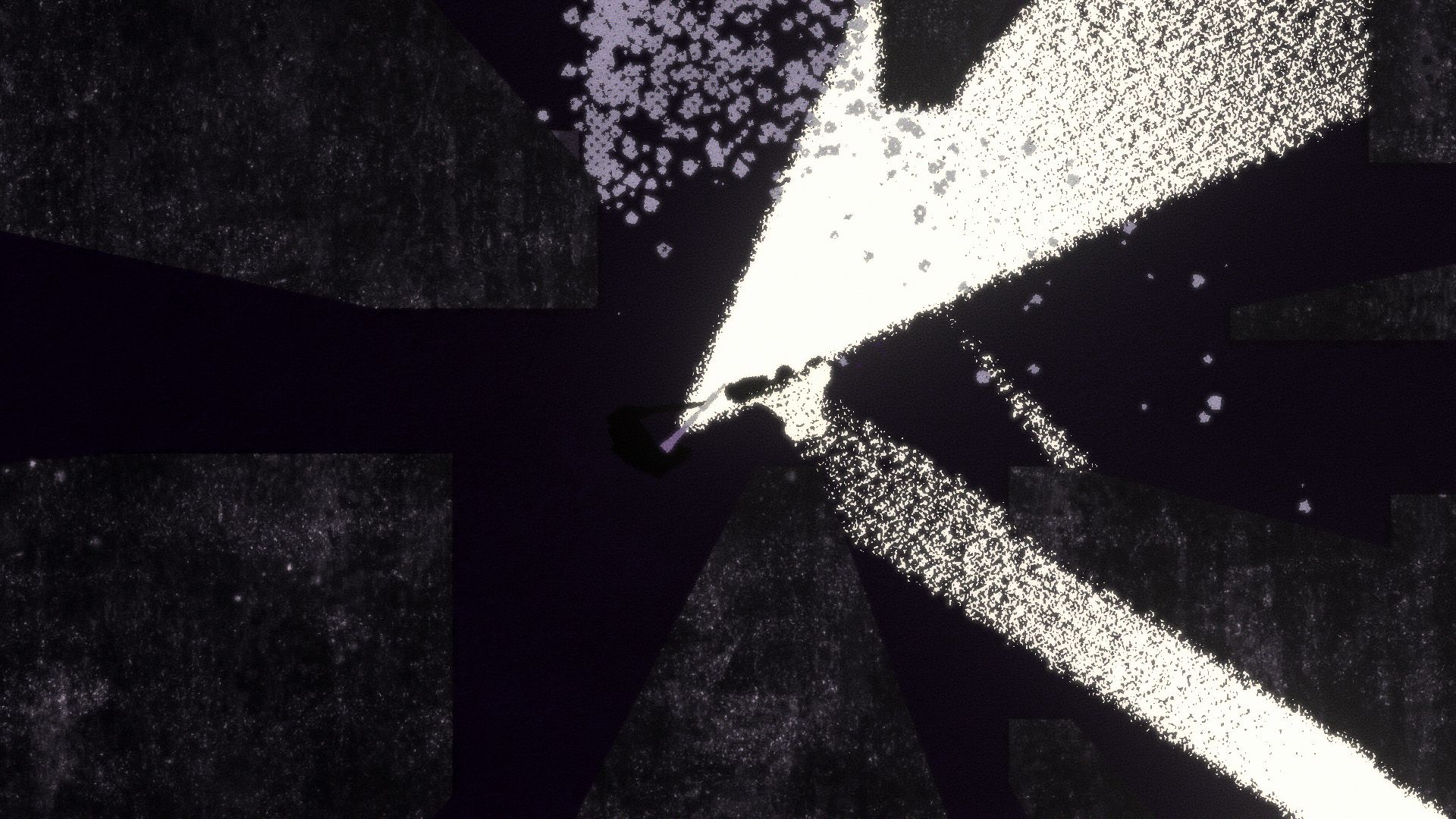

This white hot simplicity burns through the entire game: your purpose is clear, your controls are move, grab and smash, and the awful vignettes of screaming primate exploding human blood balloons are rendered in simple silhouettes and blocks of colour. Every screenshot could be framed and hung on the wall, provided you were the interior decorator of the damned, because Ape Out is extremely, joyously violent. But it’s okay, because these men kidnapped a gorilla and locked it in a confined space, so they brought it on themselves.

To escape the research facility, army base, boat, or office tower block you're in -- we do not waste time considering why an office block is keeping a caged gorilla in the penthouse office under armed guard -- you must frantically knuckle through different procedurally generated levels, travelling from a door on one side to (usually) a door on the other. Armed men patrol the levels with different guns, first rifles, then shotguns, machine guns, explosives… eventually rockets and flamethrowers. All are instantly recognisable, and require slightly different approaches. The lads with explosives, for example, blow up upon being smashed, so you can’t plant them into a wall too near you, or they’ll take you down with ‘em.

You can hurl boys in whichever direction you’re facing. If they hit anything along the way they scatter like meat confetti, leaving body parts and a spray of blood on the carpet. But while you can smash and grab your enemies (and hang on to them, using them as a combined human shield and weapon, aiming their panicked gunfire by bodily hauling them around), your skin is weak. The more damage you soak up, the more you leave a trail of your own blood behind you, and you can only absorb a few direct hits before you drop. On death you respawn almost instantly at the start of the level, but a level with a slightly different layout due to the proc gen of it all.

The speed at which you can have another go, combined with the death screen that shows you how far you got on your last attempt, means you’re eager to smash more chumps rather than frustrated at your failure. It is a salty tube of gorilla-flavoured Pringles. Once you twig that your goal is escape rather than total carnage, that the carnage is in fact merely a pretty side effect, you get sort of tactical. Developer Gabe Cuzzillo told me at GDC that Ape Out started as a stealth game, and once you know that, you realise you can sneak around enemies, or trick them by looping back on yourself, and get them so confused they accidentally shoot each other.

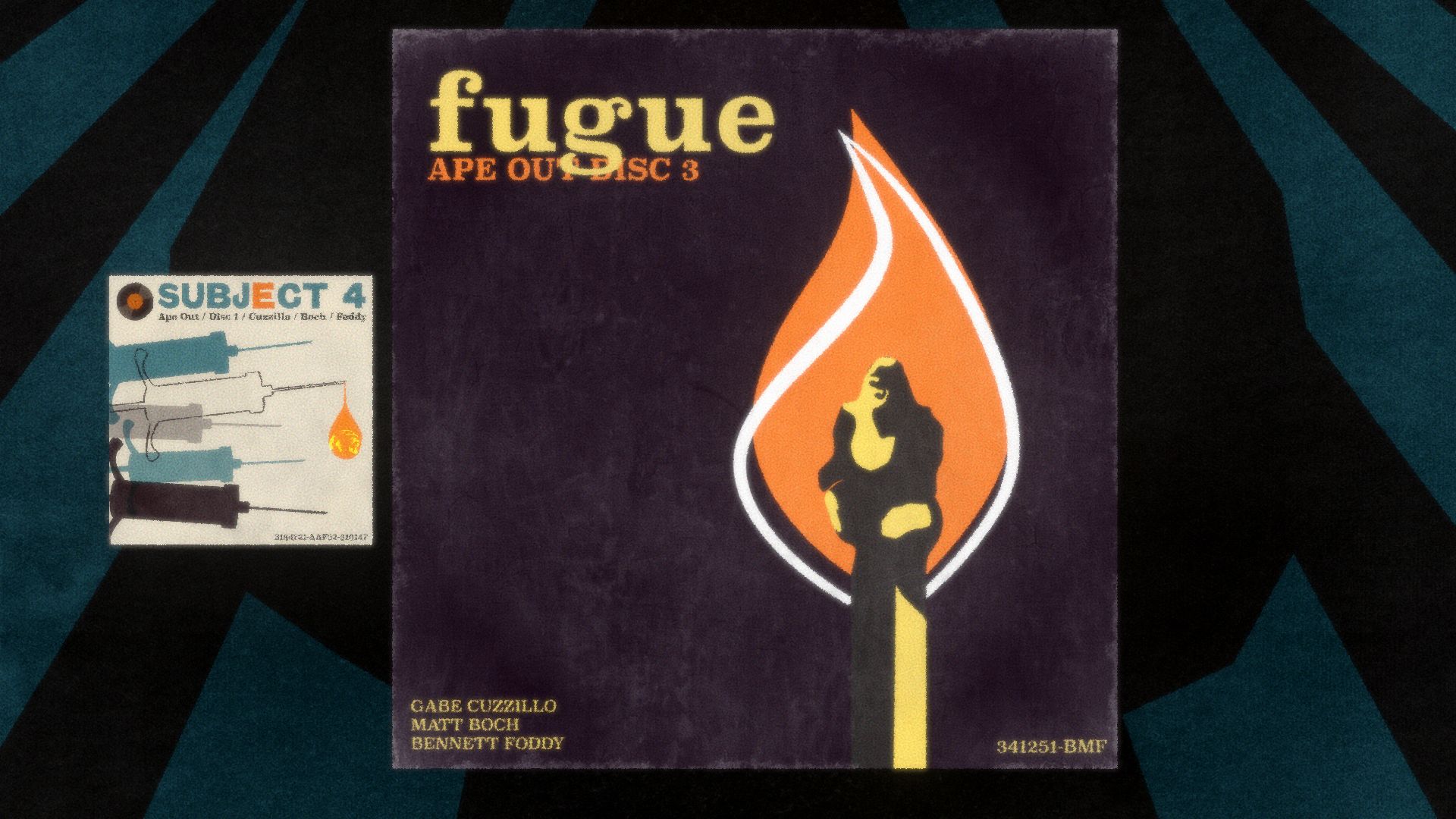

At this point you’re thinking that I haven’t mentioned the jazz yet, and yes, jazz is a big influence on Ape Out. The game is divided into four sections that are styled as jazz albums, with an A and a B side; they have album covers and the levels are track listings (Bennett “Getting Over It With Bennett Foddy” Foddy was brought on for art). The whole game has an algorithmic masterpiece of a score by Matt Boch, frenetic drums that grow louder and faster as the violence increases, or dip into a lull at times of calm. Each death is greeted by a triumphant crash of cymbals, so you feel like a conductor in your own mad orchestra of carnage. You, somehow, feel part of the creative process. The way you smashed three men together, just so, leaving a blush of red over the blue carpet, and adding just a soupçon of orange viscera from your own wounds. “Ah, exquisite,” you think. “Perhaps I was always meant to be a great improvisational artist.” But there is no time to pause and admire your work, for you must knuckle on and create another.

Despite the repetition, after many deaths, it does not feel repetitive, because other variation is added. Some of the levels take place in darkness, and you must avoid the swinging torch beams of the guards. Others have explosive barrels of oil, or bombs falling from the sky, a last ditch effort to subdue your primal rage. One extremely cathartic smash and grab takes place in a zoo. And there are smaller details to admire, too: the music for the stage set in a military base sounds like marching snare drums. Bloodsoaked carpet makes a squishy noise when you walk over it. Trees that are set on fire burn to nothing. It’s a game where it feels like everything has been very carefully thought about, so you don’t have to, except when you pause for a minute and notice something -- perhaps one particular bit of kinetic typography on a level title -- and go: blimey, this is all spectacular, isn’t it? And then you throw a man out of a window and he makes a tiny splat on the road below. Tee hee.

If nothing else, this is a game where you, a gorilla, can punch a man so hard that he crumbles into his constituent parts, and then pick up his arse and hoof it at one of his mates. I don’t know what else to tell you.