That belongs in a (digital) museum

The creators rethinking art exhibitions in cyberspace

When was the last time you went to a museum?

I still do, on occasion. Maybe not as much as when I was a hapless kid trailing around after grandparents, bothering the goldfish in the National Museum of Scotland’s lobby. Twenty years later, I can at least pretend to have more interest in the installations -- but I do miss the fish.

Last year, I visited several on a trip to Berlin, but they weren’t traditional museums (nor were any of them the capital’s gaming-centric Computerspielemuseum). Indie games festival A Maze Berlin had at least four digital galleries gracing its dusty east-German hall last year, from a multiplayer showcase of VR artwork at the Museum of Other Realities to extensive studies of Marcel Duchamp’s infamous Fountain.

We’ve seen these pop up before, and it’s starting to feel like a trend -- building museums out of pixels and polygons rather than white paint and plaster, to compile art, games, studies or simple little curiosities that might not fill out their own release. Whatever it is, something about the ancient museum model has stuck in video games. I reached out to several creators to find out why.

“It's accessible. You can distribute it for free,” explained George Buckenham, one of 37 developers and artists to contribute to the first Zium Museum in 2017. While an active curator of real-world games exhibitions like Wild Rumpus and Now Play This, Buckenham finds one of the biggest strengths of virtual museums to be just how accessible a simple executable file can be.

“A lot of curation comes from the urge to grab people by the shoulders and shake them and say ‘Hey! Look at this! Isn't it great? Isn't it really fascinating?’” they said, “And this is a way of distributing that to people within their homes.”

Likewise, moving away from a physical space means installations like Zium are free from more logistical problems inherent with real-life museums. There’s an entirely separate skillset needed to construct the space, but ongoing maintenance isn’t quite as intense. Where physical events last for a few days or months, Buckenham sees exhibitions in digital space as more durable.

“You have to pay people to stand around and fix things if they break, and you have to pay for space, and all of the other costs with doing something in the real world. And so, after a while, everything gets packed away,” they explained. “There's definitely an appeal to setting up a digital space where you don't have those ongoing costs.”

Some of these museums take a more collaborative approach to installation -- a gallery built around artists working to a brief or theme. Games and digital creations can easily be placed together in bundles or compilations online, but placing them within a three-dimensional space can provide context a straight-up list never could.

“I was thrilled to explore the Zium,” said Edinburgh-based designer and community organiser Vaida Plankyte. Like Buckenham, she was involved with Zium, creating an installation named Apartment: a table with a phone, and a plate with some crumbs on it, in front of a window.

“When you approach the table, a song starts playing and reflects on the objects present,” explained Plankyte. “The song is called Crumbs, and it's about getting better and being grateful for your relationship, and its genre is ‘lo-fi’.”

For Plankyte, the structure of the museum space itself is an essential part of the experience -- heightening the individual works by placing them alongside similar works, their particular placement within the building, and so on.

“It's really interesting how the digital-physical space of the museum made me feel like my work was more... tangible,” continued Plankyte. “Seeing the installation on a floor surrounded with other installations of the same vibe, felt like I was part of a bigger whole in a way that a list of grouped submissions on a page just couldn't provide.”

Plankyte said that she is grateful to have been able to take part, and is already looking forward to what The Zium might inspire in the future. Plankyte is excited about the possibilities of translating physical spaces into a digital version, and “keeping the familiar structure that works well, while complementing it with installations that wouldn't be easily realisable ‘in the real’.”

Other galleries don’t bring together the work of individual artists, but entire communities. Around the end of 2018, independent game studio Crows Crows Crows launched a fan-art museum built of contributions from members of its community discord.

“I’ve never really engaged much with the people who play my games before,” said studio director William Pugh. “Making the museum with them has been interesting, because of the sheer volume that the internet can throw at you. Someone made a miniature figurine, we’ve had 3D models, animated things from Unity. We’ve got a big nose that sneezes and drips snot.”

For Pugh, community curation runs in the family. With his parents creating and curating local festivals in a small north-English town, the game developer sees The Crows Crows Crows Community Museum as carrying that torch.

“Curation’s a pain in the ass -- we’re not going to get everyone’s in there -- but it’s interesting working with a community,” he said. “It’s a group of people with different experiences and interests and different things they consider to be beautiful.”

The communal nature of the project meant Discord members who may not consider themselves artists could find a platform for untested art -- including the creator of the aforementioned miniature figurine.

“I was very proud to be included,” said community member and contributor Phoenix DK, who admitted to having “very little” prior experience in digital art. “Not everyone who contributed something got in and there's such a variety of things to look at & listen to in the museum.”

“There is an ever-increasing number of folks who have now played the ‘game’,” she added, hinting that the museum has kicked off potential plans for similar projects in future. “It's definitely led to a lot of conversations about all sorts of collaborations in the various channels we have.”

These are all things that physical museums and installations can do just as well, though. Where digital exhibitions can differ is in structure. In cyberspace, the laws of space and time aren’t quite as restrictive.

Buckenham explained that the real world has very real restrictions on manipulating the space of your exhibition: “Curation is so much about shaping the physical environment to give rise to experiences. What order do you show things in? What does it say to put this piece next to this piece? Is this room going to be noisy & full & exciting, or is this going to be a calm contemplative space?”

“Within a digital space,” they said, “All of these things become optional. You can have a giant room if you want. You can have teleporters if this bit should connect to this bit, but they're not actually next to each other.”

The established context can even play a part in how the exhibition space is perceived by visitors -- whether it’s a sleek and shiny unreal project, or something a little blockier. “One of my favourite virtual gallery spaces is localhost, which is built in Minecraft,” admitted Buckenham. “There are a lot of expectations set by Minecraft, a lot of texture to rub against.”

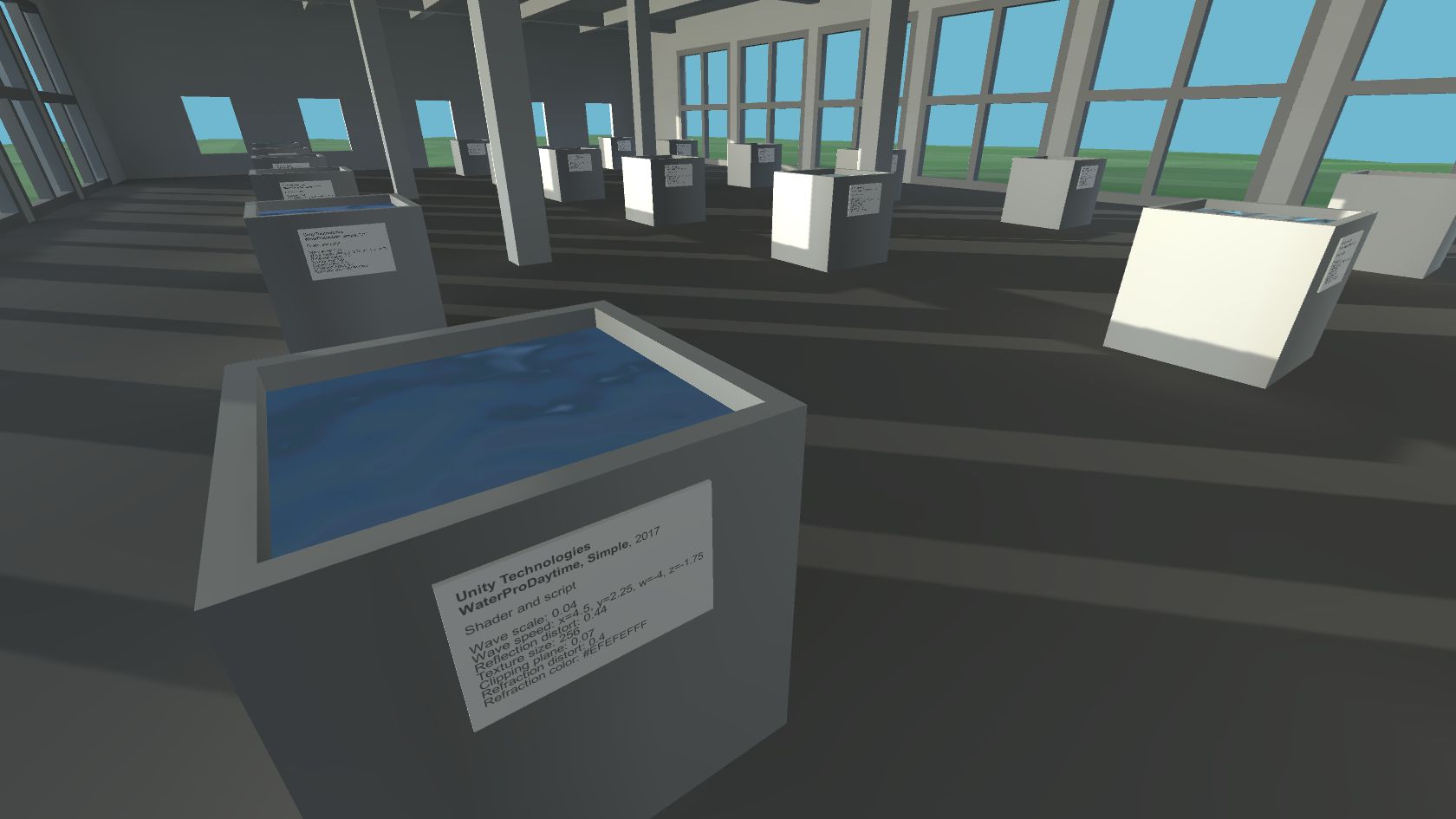

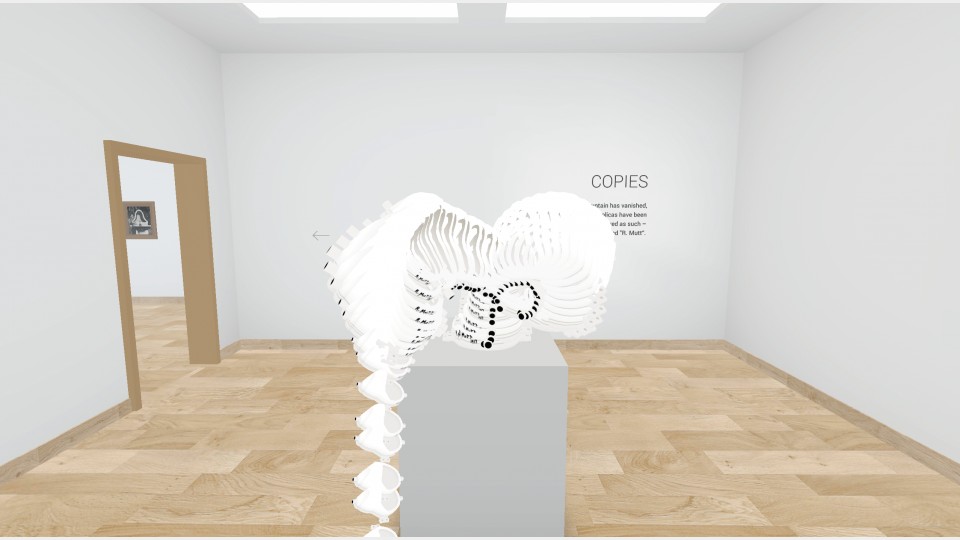

This un-reality has let some game makers go wild with concepts, and it’s this absurdity inherent in virtual spaces that gives power to digital museums. We can explore spaces like Pippin Barr’s v r 3, dedicated to the challenge of trying to represent something as simple as water in a 3D space. Meanwhile, The Museum of Other Realities plays with scale in outrageous fashion, letting you walk up to a miniature diorama of a small cottage and instantly shrink yourself down to size.

Curators and creators shouldn’t go overboard, though. Much like a real installation, space matters as much as what’s nestled within it. Virtual spaces simply give a far more expansive range of tools to work with.

“One thing I think is the same is the sense of pacing and rhythm and carefully selecting things,” Buckenham elaborated. “Especially with a digital space, it's easy to just add more things -- because building a new room is free! -- but art is really exhausting to look at. You still have to, well, curate the selection.

“Sometimes a piece wants to be alone in a room, so it can make the best impact. Everything should add to the whole experience, maybe some thesis you're trying to argue for by the careful arrangement of objects. It's still the same thing, underneath.”

So should National Gallery curators start packing up their desks and going digital, then? Probably not, Buckenham reckons.

“I don't think it is the future of exhibitions,” they admitted. “I think people will always want to go see things in person, there will always be a wider scope of what you can do in person than you can do in a digital space.”

After all, and perhaps most crucially: “It's harder to go on a date to a virtual gallery!”