Gaming Made Me: Quest for Glory IV

In this week's Gaming Made Me, Richard Cobbett reminisces about an old crush. No, not on the sexy vampire villainess of this classic adventure/RPG hybrid, but on one of the first games that taught him to demand better of story in these silly little computer game things.

Quest for Glory IV was the game that told me what I was missing in graphic adventures. It told me what I wanted from RPGs too. It's a story of heroism, of course, and of bravery, even if I do say so myself. But it's more than that. It's one of the first games that really showed me the importance of even the simplest interactions, and which set an early benchmark for characterisation I still feel sorry to see most games fail to even reach for, never mind successfully.

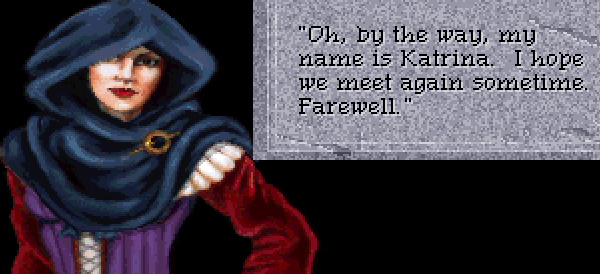

It all started with a woman called Katrina. Let me tell you about her.

Katrina is the first friendly face you see in the land of Mordavia, a sealed off country of dark marshes, forgotten temples, paranoid villagers and persecuted gypsies. She's the only friendly face you're going to see for quite a long time. Nobody else likes you. Nobody else trusts you. In time, they will. For now though, you're simply a stranger, and they resent your presence almost as much as they need you. Only Katrina comes across as anything but jaded, suspicious, and ready to run you out of town if you so much sneeze like an outsider.

It says something about Mordavia that your only friend is also the world's biggest threat. It says something about Quest for Glory that this friendship turns out to be completely genuine.

The Quest for Glory series was never short of friends, in-game or in reality, though it never had a huge impact on the gaming world as a whole. The series, with its mix of adventure style world and RPG stats and character classes, was never really ripped off. The things that drew me to it remain largely untapped ground. I loved that each one took place somewhere brand new - the European village of Spielburg in the first game, subtitled 'So You Want To Be A Hero', giving way to the desert city of Shapeir in the sequel, Trial by Fire, before moving to the African savannah in Wages of War, and finally a fantastical version of Greece in the final part, Dragon Fire. They all shared a few elements in common, like a love of puns and lots of recurring characters, but all had their own unique feel and twists. Spielburg for instance was purely a base of operations, with the action out of in its forests, while most of the action in Trial By Fire took place in the city, with only very occasional trips out into the hostile desert for random acts of heroism.

The Quest for Glory series did many brilliant things that shaped how I saw both adventures and RPGs afterwards. I mostly came to it from the adventure side, which helped the freedom and scope of your actions seemed incredible. It offered Fighter (with the option to be promoted to Paladin), Magic User and Thief classes, all with custom side-quests and their own ways of solving the problems in front of you. Magic User was always my favourite as it came with an ever-increasing bag of tricks to play with, and usually played fair. If you had a spell like 'Fetch' and needed to retrieve an object, casting it would normally work. If you had an attack spell, responses would be coded in for most situations, rather than lumbering you with a boring failure message. You were encouraged to experiment with your abilities, just to see what had been coded in. With low skills for instance, clicking your trusty Thief Kit on your hero would lead to him extracting his door-opening device of choice, and accidentally stabbing himself through the brain. More skilled? Click! Congratulations! You successfully picked your nose!

No, it's okay. Take a minute to finish wincing at that one.

This was the kind of interaction density I always craved in adventures, not to mention the first step down a path that very disappointingly failed to lead anywhere - a switch from traditional puzzles to more freeform problems, which could put more emphasis on how you solved things than whether or not you successfully read the designer's mind. Quest for Glory didn't really offer that many extra options and alternative solutions, more treats like lots of cool deaths and dreadful puns to reward exploration, but it felt like it did, and that's what mattered.

While I like the whole series (with the possible exception of the third, which does nothing for me at all), Quest for Glory IV: Shadows of Darkness is by far the best. It's also the least welcoming. That's part of the charm. Its world, Mordavia, is far and away the RPG world I've most felt like I was making a difference in, not because there are lots of moral decisions to make (there aren't - you're a Hero, and the game will kill you if you try to be anything else), but for how much you affect the characters lives. Here, even the villains are worth trying to save.

The Rusalka is the first you're likely to meet. In Slavic mythology, a Rusalka is a mix of mermaid and succubus, luring unwary men to their deaths. You soon meet one in Mordavia, a naked woman in a lake who pleads with you to join her in the water. Accept, and you're dead. She drags you down. You fool. But this is Quest for Glory IV, the game where you can befriend a number of the monsters, and completely change your perspective. A simple act of kindness, and suddenly the Rusalka is more than just another environmental threat and a sexy way to snuff it. As dangerous as she remains, she now begs you not to enter the water, knowing that if you do, she's cursed to have to drag you down to the depths. If you're a Paladin, you can save her from her fate. If not, at least you took the time to take the edge off it, if only for a few minutes. It's the first real hint that your real job in this miserable land isn't to save the world, but to bring hope and make it worth living in. Not necessarily by kicking green arses until everyone cheers up.

(Unrelated to this, I should probably mention how much I loved this setting. I'm a big mythology buff, so it was great to get to play around with creatures like domovoi and rusalka instead of more bloody goblins, kobolds and so on. Even better, it treated them in a very casual manner, unlike every other fantasy novel or game that feels the need for fifteen thousand pages of lore about what these mysterious 'dwarves' and 'elves' are. In Mordavia, they just Were.)

Katrina is in much the same boat, despite being the instigator of all the game's troubles. She's one of my favourite... what? Villains? Antagonists? Opponents? It's tough to say, and that's why I like her. Quest for Glory IV is one of the few games I've ever played that embraces shades of grey from a positive direction, which is all the more surprising for the sinister setting. It's a world where the villains don't simply have excuses, but often sympathetic ones that almost overshadow the reason a Hero is needed to stop them in the first place.

As far as Katrina specifically goes, she's the kind of character who could very easily be a straight-up villain. She's a vampire mage who lives in a spooky castle, is plotting to blot out the sun by releasing the elder god Avoozl on an unsuspecting world, and has been spoken of since the second game as your previous nemesis' Dark Master. She's self-centred, manipulative, and while the story has plenty of sympathy for her, she herself lacks much real empathy.

Despite this, it's hard not to like her, or feel sorry for her. Almost nobody remembers her in her monstrous form, hair spraying out and fangs stabbing from her mouth. They remember her as Katrina, the loneliest woman in Mordavia, who shows up outside its walled town every now and again for what she seems to consider dates, and whose fatal flaw is not realising the consequences of what she's up to. It's notable that most - though not all - of her 'evil' credentials are implied rather than shown. Her lowest point witnessed in the game itself is that she's kidnapped a little girl, Tanya, from town and turned her into a vampire daughter. It's a genuinely sad, touching sequence, and one which makes a great point of focusing on how the parents are suffering as a result and how important it is that she be cured and returned... but one that also makes a specific point of showing that Tanya is fond of her "Aunt Trina", and that even though Katrina is heartbroken to lose her, she shows no intention of snatching her back or otherwise trying to balance the books. The closest she gets to taking revenge is...

Well, it's an interesting scene. It comes shortly after you discover that she's a vampire, and find yourself standing over her coffin with a very convenient stake and hammer supplied by one of her other enemies - a misogynistic wizard called Ad Avis, who you defeated in QFG2, and is currently chafing at being under her thumb. If you go ahead with that, you remove the one thing standing between him and horribly killing you in revenge. If not, Katrina wakes up to see you standing there, immediately (and let's be honest, not unreasonably...) assumes you were just about to stake her, and goes... ballistic. What follows is one of the most bizarre character tone shifts ever, cutting away to the castle's dungeon where Katrina, who starts out dressed in a modest hooded ensemble, before letting her hair down for a more flattering corset look, suddenly shows up dressed from head to toe in spiked leather, whipping the hero like an undead dominatrix. As silly as this is (I defy anyone not to laugh when the scene cuts to it), it's still true to her character. If getting what she wants by being a friend won't work, then damn it, she's willing to play the villain to regain control of the situation, forget being Miss Nice Dark Mistress, and just force the damn hero to play his part like she could clearly have done right from the beginning.

It's the undertones of this scene that make it more than just a bit of fan-service, particularly the way that it's clear from her reaction that she's not bothered that you tried to kill her per se, more that she's upset at the betrayal. It's probably the only time in RPG history that a hero has ever been chained up in a torture chamber, trying to explain to his nemesis that no, he really wasn't trying to kill them. Admittedly, since the other options available before she woke up included trying to steal a kiss or cop a feel, it's probably a losing argument. (I don't remember if you lose Honor points for trying either of those, though you clearly should.)

In mechanical terms, the relationship between the Hero and Katrina immediately struck a chord with me. It was one of the first games I remember playing that really explored how simply being interactive can turn a relatively simple thing into something more meaningful. In raw screen-time terms, Katrina and the Hero spend very little time together - but it's doled out very carefully, for good effect. Unless you abuse save/reloading for instance, you only ever get a handful of questions every time you meet. By the time she's revealed as the person responsible for the game's ills, it's not a shock because you didn't guess what her deal was, but because it turns out that she really is the lonely, sympathetic character she always seemed to be. She just also happens to be on the verge of starting the Apocalypse. Nobody's perfect.

(In the final game, Dragon Fire, it's possible to rescue her tormented spirit from Hades, at which point she admits she's actually glad her plan didn't work, is a little upset that she's seen as a villain by her people, and directly states that she never really considered the Hero her enemy. They can even end up getting married and ruling a country together.)

As well as simply being a sympathetic character, Katrina also stands out in my mind as a very inspirational one - something that cemented in my head the idea that even in games, heroes and villains could be more than just snarling bags of stats and puzzles blocking the way to the McGuffin. Some people hold up Floyd from Planetfall as their eye-opening example. I use Katrina, who in my mind at least, paved the way for the anti-villains and moral choices and page after page of arguments about which faction in Dragon Age 2 has the high ground that we all expect today. At least for my part, after several hours in her company, I could never even hope to take generic evil overlords seriously again, nor as a writer, ever want to create one without taking at least as much care over what makes them a real person as a threat.

Oh. And I loved the hideous puns too. That's okay too, right?