Ghames with Ghoastus: Nauticrawl

Crawl me maybe

Ave, Citizens! As October sweeps onto the calendar, like a crowd of yokels breaking into a condemned theme park, the barrier between the human world and that of the Romans grows thin. With a rustle of laurel the veil is parted, and I, Ghoastus, manifest among you! Be not afraid, however, for Ghoastus is a friendly spirit. And this month, I aim to be more friendly than ever. My human friend Nate, you see, has been quite unwell, and while he recovers, he has ended up with a backlog of games which he quite liked, but has had no time to write about. Luckily, a Ghost Writer haunts his desk - and I intend to clear it for him!

First on my list of games, we have Nauticrawl. And it’s a hard one to describe. Let us imagine, citizen, that David Lynch, fresh from making Dune in 1984, decided to make a game. And that his premise for said game was a sort of escape room, controlled by a cantankerous virtual reimagining of the Steel Battalion controller. Intrigued, friend? You should be! Nauticrawl is utterly fascinating - and it needs to be, to motivate the player through some of the most gruelling trial-and-error play I’ve seen since Pluto held an athletics contest in Tartarus.

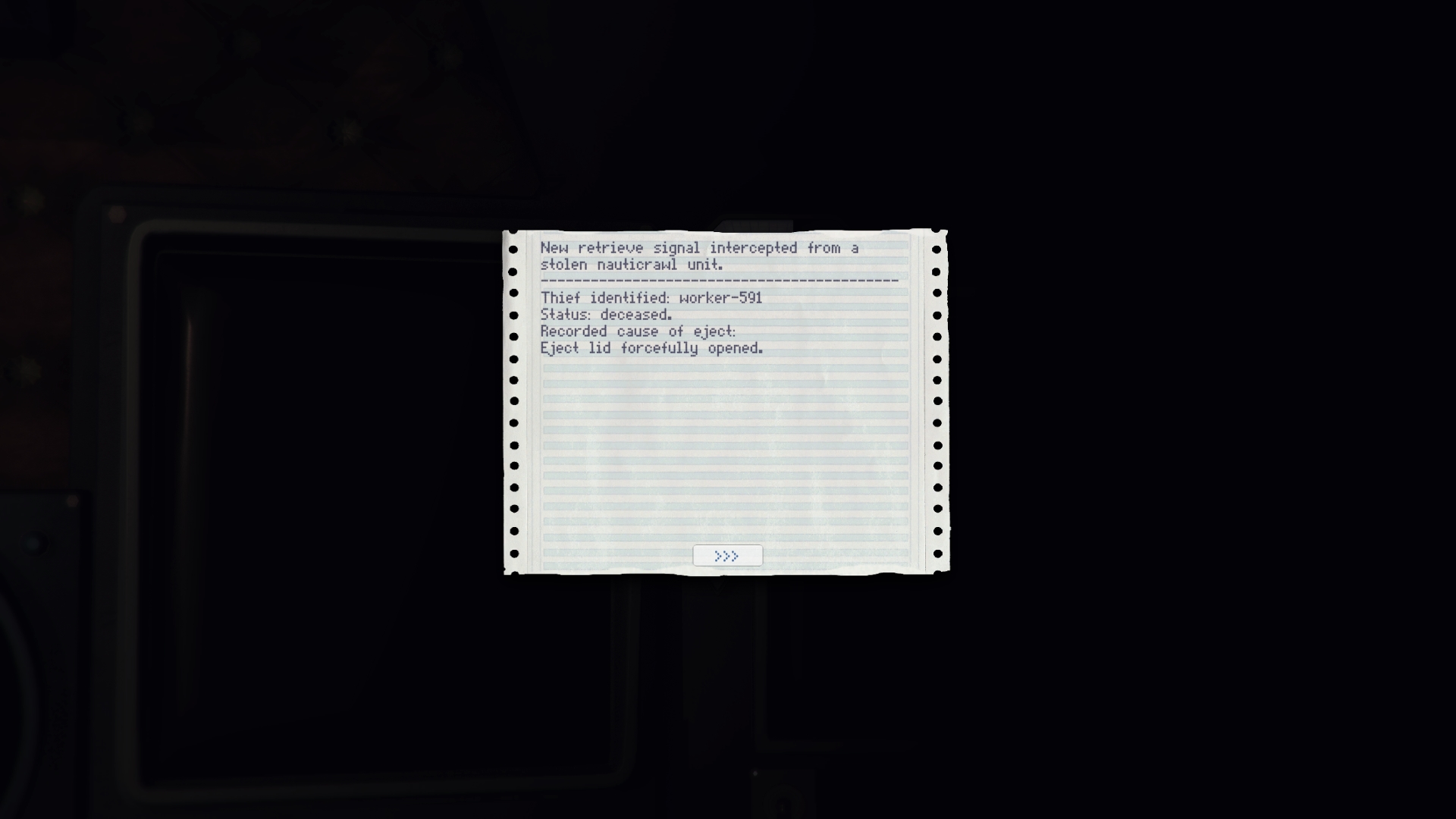

I don’t want to say much about what happens in Nauticrawl, because the drip-feed of information is what drives the game, but suffice to say it’s set in one of those brilliantly baroque science fiction settings where interstellar empires exist, but still use leather upholstery and coats of arms. Whatever society persists here, you are on the blunt end of it, and you’ve managed to steal one of your masters’ vehicles - the titular Nauticrawl.

Outside, the atmosphere is as thick, as hot and as lethal as what one might find in the lower reaches of a gas giant, and the systems keeping you safe from it are as opaque as they are temperamental. You begin in a dark cabin, illuminated only by the yellowish light filtering in through one grime-covered porthole, with absolutely no information on what you’re doing. There’s no clue even as to where an ‘on’ switch might be - there’s just banks of control machinery, waiting in the gloom. When you get the engine going, it’s a thrill.

The controls, as you learn them, are satisfyingly frustrating in the manner of Objects in Space, MirrorMoon EP, or even the majestic Envirobear 2000. You have almost nothing in the way of keyboard shortcuts mapped directly to the actions of your vehicle, so it’s a case of clicking on levers, buttons and dials to carry out your will. It drifts into annoyance occasionally, but there’s enough pleasant visual and audio feedback to keep it feeling rewarding. A little like being a poltergeist, really.

After a little while of clunking, shunting and fiddling, however, you will die - either through violent misadventure, or through something as pedestrian as forgetting to shore up power in the vessel’s battery. But death, as any ghost can tell you, is just a phase. Soon you’ll be back in that stygian cabin, with one more idea of what not to do. I think it was the physicist Niels Bohr who defined an expert as “someone who has made every conceivable mistake in their field”, and this serves as a decent guide for completing Nauticrawl.

Impressively, the game isn’t quite the blank-faced, passionless observer you think it is, either. Contrary to what you might expect, it’s quietly taking notes on how you die, and soon begins offering subtle, elegantly diegetic hints on how not to expire so often. And it does all this without ever seeming like it cares. I’ve never described a game’s interface as Tsundere before, but here is just such a thing. Gaining favour with good old Augustus was much the same: persevere, and you will be rewarded.

Nauticrawl isn’t a long game, and although its complexity expands pleasingly as it goes on, once it’s done it’s done: I can’t imagine finding a reason to replay it. But there’s nothing wrong with that at all - it’s a singular experience, and it does what it does well. Even if you find yourself getting bored after a couple of hours, I’d still make the argument that it’s worth the asking price as a piece of interface design, and as an exercise in creating atmosphere. For creators interested in evoking grand-scale SF without actually showing much visually - admittedly a niche market - it’s a must-buy.

So there you have it - Nauticrawl. Not the most relaxing play in the world, and not one for the impatient (while I have a tolerance born of undeath, Nate’s attention span suffers greatly with puzzles) - but a neat little masterclass in minimalist worldbuilding, and a cracking experience for those who enjoy analogue controls. Go forth, and examine it!