Wot I Think: John Wick Hex

Wicky Wicky Wild Wild Hex

You don’t play as John Wick in John Wick Hex. Not really. Instead, you play as Keanu Reeves’ choreographer, in close negotiation with the great man’s agent. Want Wick to dash behind cover while throatslamming a goon, then toss them to the floor, grab their gun and shoot a second goon’s ear off before yeeting the empty pistol at a third? That is absolutely within the terms of Keanu’s contract. Want Wick to dodge an incoming blow, then double-handed-clap-slap his attacker on the cheeks? You’re the boss. Want Wick to jump over a very small object? Ok, so he can’t do that. Union stuff. Lots of paperwork, and no-one wants to let him near a pencil.

Refusal to do very basic stunts aside, however, John Wick Hex is a frequently comical, tightly-tuned, hyptonising murder-puzzler which is -- if you’ll excuse the insensitivity -- a doggone blast to play.

First things first, though -- what’s all this ‘Hex’ business about? Well, it’s the name of the sharply-dressed baddie who becomes the Wickster’s primary murder target in the game, after he takes J-Dubs' buds Charon and Winston hostage. This gets right on John’s wick, and when Hex dumps a bucket of goons all over everything in his way, the gun-fu begins.

I only watched a JW film for the first time yesterday, after I’d already finished the game, so franchise fans might get more out of the plot than I did. From what I understand, however, the film’s stories are largely vehicles to ferry Wickiam Blazkowick between shootouts, and it’s the same deal with the game. It works for me.

The plot, a prequel to the movies, is delivered via snappy comic strips between stages, in which Ian McShane sounds Bored McShitless as Winston, but Troy Baker’s seething Hex and Lance Reddick’s suave, foreboding Charon more than make up for it. Keanu Reeves himself is absent, presumably still recovering from the trauma of being selected for temporary deification by the internet.

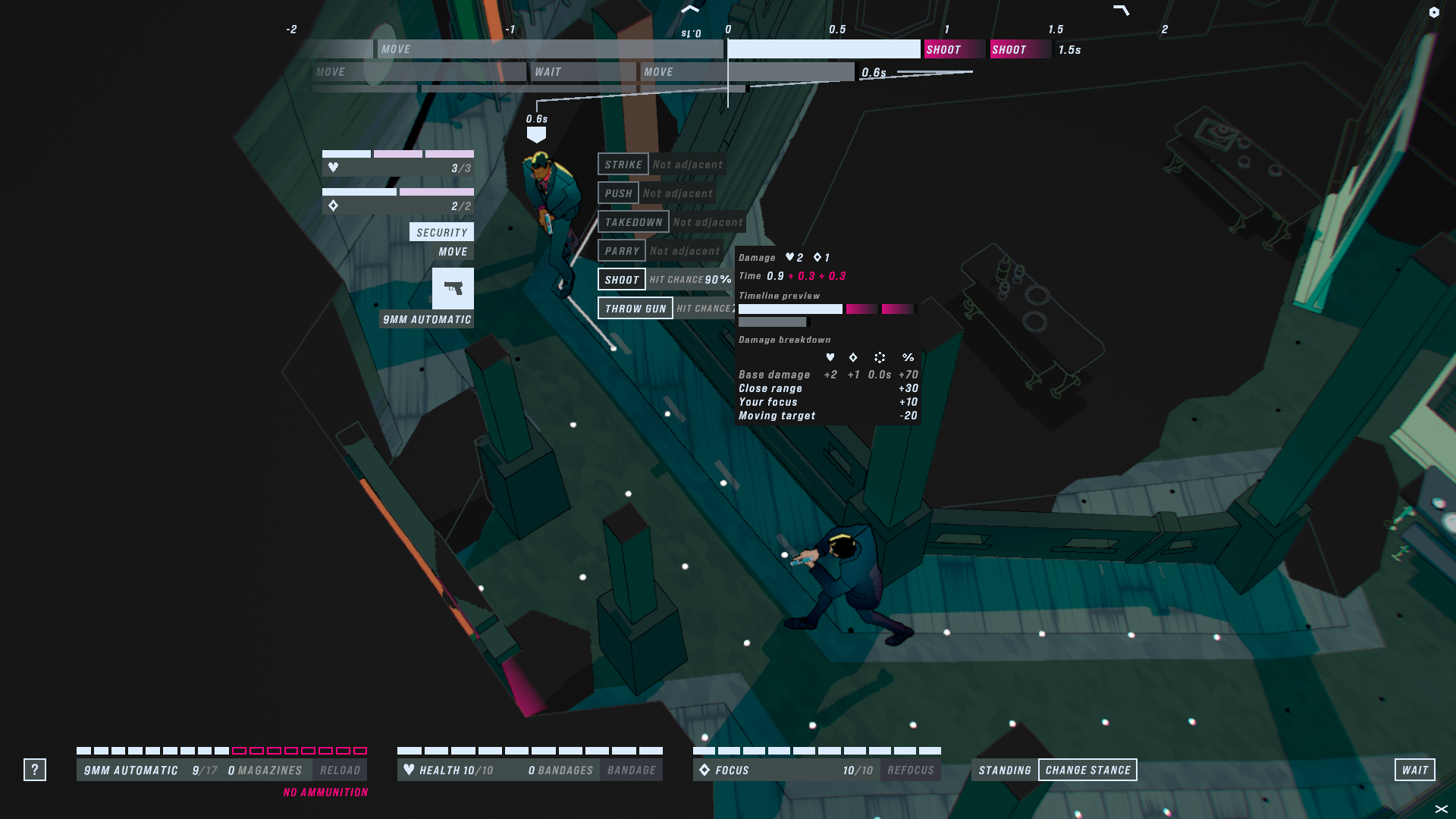

Hex isn’t just the name of a villain, though: it’s also a reference to the near-invisible grid (highlighted by unobtrusive dots), on which Wick dances with goons across the game’s 40+ levels. Rather than the traditional turn-based affair you might expect from this setup, however, all actions are rationed based on time.

Moving to an adjacent space takes 0.4 seconds, for example, while shooting a pistol takes 0.9 seconds of build-up, then 0.3 seconds apiece to fire two shots. Shots fired both by and at Wick have a percentage change to hit, affected by whether the target is moving. Wick can crouch (0.5 seconds), which makes him harder to hit and more accurate, although he’ll have to stand up again (0.5 seconds) afterwards, if he wants to walk instead of roll (0.6 seconds). This might sound complicated, but it’ll all fall into place by the time you’ve finished the concise tutorial stage.

For more complicated actions, J-Wix has a resource called ‘focus’. You can use it to roll, or to dodge an incoming melee attack, but it really starts to define the flow of Hex when it’s used for takedowns, or pushes. Takedowns slam troublesome goons into the floor, and allow you to pick an adjacent hex for John to wick his way into. Pushes let you thrust an enemy back a few tiles (causing damage but also sending John along with them - a great way to avoid bullets), or dash behind cover, or hang around the entrance of a nightclub shouting ‘no trainers’ and punting guards out the doors. Highly recommended, that one.

In each level, you’re attempting to take out screens of goons before they get a shot or a punch off, and weaving around any that do. Throw in rifles and shotguns with different damage and time stats, a few armoured goons, some bosses that require you to melee their focus down before you get a decent hit percentage, and the aforementioned gun yeetability, and that’s you sorted.

There’s a period between getting used to Wick’s repertoire, and the game ramping up in difficulty, where Hex’s toolset can feel quite restrictive. The safest plays aren’t always the most enjoyable, but generally, Hex keeps things challenging and engaging by applying a filmmaker’s lens to enemy placement and environmental layout. Goons emerge from behind stairwells, elevators, and industrial shipping crates. Sure, you’ll be doing the same moves on them, often in the same combinations, but you’ll never perform a spine-shattering Judo throw on a henchmen into the same river twice, as the philosophers say.

So, you’ve got Hex the baddie, and Hex the grid, but perhaps more than either of these though, the titular Hex is the curse inflicted on any simulated mortal foolish enough to step against John Wick.

The internal rhythms of the ready/set/action tactics completely sell the idea of this hitman who has the supernatural ability to storyboard his own reality. Combat is a black magic bullets-and-body-slams-buffet, balletic enough to make Bayonetta blush. Frenetic and elegant, it’s possessed of a self-awareness that stops just short of self-parody.

Austin Wintory’s soundtrack of manic techno and moody, pistols-at-dawn guitar feels integral. So much so that I’d tentatively place John Wick Hex alongside Hotline Miami, Ape Out, Frozen Synapse, and All Walls Must Fall as a work where the player navigates the soundtrack as much as the environments. Melodic, rhythmic, and chemically cerebral, it interprets violence not as a forward hurtle, but a series of call-and-response couplets.

Then there’s the replays, which, as far as I can tell, the trailers have sold as fluid, cinematic coup-de-gras where you sit back and watch your perfectly choreographed action set-piece come to life. They are not this. They’re hilarious and awkward, and I love them for it. Wick jankily shuffles between hexes, sidestepping point-blank shots and crab-walking up stairs, while polite henchmen wait patiently for him to punch them, lie down, get up, and do it again. Audio plays out of sync, Wick lopes around like he’s caught himself in his zipper, and it’s great.

At least the replays allow you a bit more time to admire the levels: labyrinthine clubs, mansions and warehouses that feel like a natural extension of the grid they’re all based on, without giving up a sense of place. One stage has you ducking and weaving behind hexagonal statue plinths. Another has you popping out from behind trees, slapping fools, then disappearing again. A snow-dusted hedge maze and a neon-splashed nightclub are highlights, but there’s a constant effort to change things up. Breaking line of sight is one of the key defensive moves you’ll be relying on, so it’s reassuring that so many architects in the game’s universe have got John’s back.

Those same architects could have done with just a bit more allowance for setpieces, though. The closest you’ll come to an environmental hazard is elevators. Press a button. Wait out a timer. Get attacked by some goons while you’re waiting. Nice surprise the first time, but there’s too much of it. Have John Wick set fire to a big pile of money again and give that a timer. Have him defend a dog rescuer for 20 seconds while all the dogs escape through a special dog escape hatch. Whatever.

Another thing that’s fun the first time but gets increasingly dull is what happens when you’re surrounded by two or three goons. It always ends up going like this:

Punch goon one, which stuns them, giving you time to punch goon two, which stuns them, letting you punch goon three, by which time goon one is just waking up again. I’m not sure whether this is some unintentional oddity with the timeline, or completely deliberate. Either way, the game rewards you for finishing levels quickly, so it probably didn’t want me to keep relying on it. Still, if you offer me cheese, Mr Bithell, I will take it. It does make from some great replays.

The weapons aren’t hugely exciting, either. Every gun but the basic pistol and later, a carbine rifle, felt very situational and a tad slow to suit the way I ended up playing. Given I was playing a character who’s supposed to be able to murder a club full of gangsters with a box of crayola, not getting to experiment with anything but guns and MMA was a bit disappointing.

All that said, I had a great time with John Wick Hex. It tiptoes the line between tactics and puzzler in an engaging way, has a ton of character, and feels exactly as minimal as it needs to be: you pick up a working vocabulary of Wickensian tricks, just in time to be tested on them. Its slip-ups tend to just make it more charming, while most repetition can be offset by going for challenges that ask you to play quicker and smarter.

Hexcellent? Hexceptional? Maybe. Certainly, much better than Hexpected.