Persistence & Permadeath: progression in Spelunky, Into the Breach and roguelikes

You can take it with you

Progression is so often an illusion. Many games use the idea of permanent progression as a way of tickling our lizard brains with a growing pile of loot or numbers which constantly tick up, so that we feel like we’re achieving something while we sit in front of a computer and repeat the same set of tasks over and over again.

The beauty of permadeath is that it does away with all this. Characters grow and collect things, but then they become permadead, and it’s time for a new explorer to begin their adventure. The only thing that progresses is you, the player, slowly learning a set of systems with each failure. At least, that’s the theory. We spoke to the designers of Spelunky, Into the Breach, Dead Cells and Rogue Legacy to learn more about persistence within a permadeath mould.

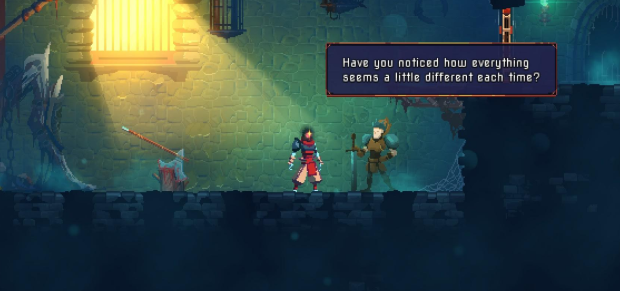

Permadeath isn’t quite as permadeadly as it used to be. There are an increasing number of roguelikes, roguelites and other games with forms of permadeath that kill a character but leave traces of progression behind. Your character might be gone, but some of the updates and unlocks they accessed live on. Exactly how this persistence is implemented, though, varies from game to game.

Take Into the Breach, a recent and brilliant example of the form which not only included persistence between playthroughs but managed to weave it into the game’s story. Losing means the end of an entire timeline, as the last remnants of humanity are claimed by giant bugs. But you can send one of your mech pilots back in time, with their experience and skills intact, to try and save the world all over again.

“We knew from the early stages of working on Into the Breach that we wanted to build the ‘try again and again’ aspect of rogue-lites into the narrative design of the game,” says Justin Ma, co-founder of Subset Games and co-developer of Into the Breach. “Following a band of heroes as they travel back in time over and over lets the player potentially feel like the whole experience of the game is connected rather than being fractured individual attempts.”

Jump back a decade, and you’ll find these persistent elements in the game which first introduced many of us – or at least me – to the concept of permadeath: Spelunky. It’s structurally a classic roguelike, with your spelunker descending deeper and deeper below the surface until they die, at which point you have to start again from the shallowest levels of a freshly-generated world. Until, that is, you meet the Tunnel Man.

In exchange for payment – cash in the 2008 freeware original, equipment like bombs and ropes in the 2013 remake – the Tunnel Man will dig you a shortcut that can be used to skip immediately ahead to later levels.

“I think that in games there are two things that can make play feel meaningful. One is a sense that your actions are having a permanent, positive effect on your character and the world around them,” says Spelunky designer Derek Yu. “The other is that your actions have consequences – namely, if you fail, you lose something that has some real value to you within the game. The randomness and permadeath of roguelikes are a great way to add consequences, but the high level of challenge makes it easy for players to hit a wall and lose that positive feeling.”

Spelunky works mostly on the latter principle, but the inclusion of Tunnel Man adds a sprinkling of the former too. The idea, Yu explains, was “to give players something positive that they can work toward even if they feel like their skills aren't progressing. And the home he sets up in the entrance cave offers a sense of comfort as a permanent fixture in this constantly changing world.”

Finding balance between these two principles – let’s call them progression and consequence – is the key to making persistence and permadeath work together. Fail to provide enough of a sense of progression, and players – at least, those who aren’t hardcore roguelikers – can get frustrated.

“It's not mandatory to make death a frustrating or a bad experience in a game with permadeath,” says Motion Twin’s Sébastien Bénard, when I ask him about including persistent elements in his ‘roguevania’ game Dead Cells, currently in early access.

That game gets its name from the balls of energy – ‘cells’, natch – dropped by defeated enemies. Although it also features a traditional gold-based economy, these cells are Dead Cells’ real currency, to be invested in permanent unlocks of new abilities and equipment. When you die, any cells currently on your person are lost forever. But if you can reach the marketplaces at the end of each section you can effectively bank them.

Having to bank your progress in this way, whether it’s by handing money over to the Tunnel Man or investing your cells towards a long-term upgrade, creates a beautiful tension. Namely, ‘can I get to the end of this level before that last bit of health is chipped away?’ It’s a microcosm of what makes roguelikes so satisfying in the first place, successfully balancing consequence – you die at the final hurdle and lose everything – with the thrill of progression when you pull it off, and finally gain access to something you’ve been working towards for hours.

However, it can also encourage you to play the game in ways you otherwise wouldn’t.

Which can be a good thing. As mentioned earlier, Spelunky’s Tunnel Man was tweaked between the two versions of the game, moving away from cash-in-hand payments, and towards a bomb-and-shotgun barter system. This change was intended to be “instructive to the player, since it suggests conserving items and using (or robbing) shops,” Yu says.

Push too far towards progression, however, and you risk encouraging a playstyle that’s disconnected from any real sense of consequence. 2013’s Rogue Legacy uses a similar unlock system to Dead Cells, but with one vital difference: you get to keep whatever loot you’re holding when you die. The whole stack does have to be spent before you begin your next life, but it’s enough to shift the emphasis of a run. Players might feel encouraged to sacrifice their current character in order to reach a loot chest, knowing the benefits will be inherited by their successor.

“We wanted to reduce punishment,” says Cellar Door Games’ Teddy Lee, co-designer of Rogue Legacy. “By which I mean, having a play session and gaining nothing extrinsic from it. This is one of our more contentious decisions, and a lot of people say this is what makes our game grindy, but removing that artificial punishment opened a lot of avenues to add depth and difficulty that would be harder to offer in other roguelikes.”

This decision makes sense in the context of Rogue Legacy, because it is at its heart a game about breaking the rules of roguelikes. You can even, at a cost, stop the game from generating a new level – ‘heresy!’ cry the genre purists – and instead stick with the same layout between runs. This subversion is all part of the thrill, but it does push the game away from the end of the spectrum we’ve marked ‘consequence’.

This balancing act was on the minds of Subset Games when they created Into the Breach.

“What exactly gets sent back was a tricky thing to balance,” says Ma. “If you can improve the odds of your next run considerably by sending back powerful items or skills, you might feel obligated to use a single playthrough to farm the items you'd like to start with, then abandon the run to start your real attempt at victory. Such a situation didn't sound fun so we opted for the current method of sending pilots, who are certainly helpful but are unlikely to be a primary factor in success or defeat.”

This is the key to making persistence work alongside permadeath. Dying should always be able to squeeze a yelp or curse word out of you – that all-important feeling of consequence – but a little progression can make it easier to swallow the sense of wasted time. As Dead Cells’ Bénard puts it: “Death should be turned into an exciting moment because it's the beginning of a new game before being the conclusion of another one.”