Play a messy brain in The Quiet Sleep

Defend your sense of self

Brains are squishy, veiny gobbets of flesh filled with squabbling ideas, desires and feelings. They aren’t pretty. And nor is The Quiet Sleep, to be frank. But look past this strategic-narrative game’s programmer-art visuals and you’ll find a life playing out among its icons. And within that life lies a story told through the systems of a game that somehow successfully blends The Settlers with The Sims, via the Zacklike, tower defence, and a touch of Fallen London. I’ve not played a game quite like it.

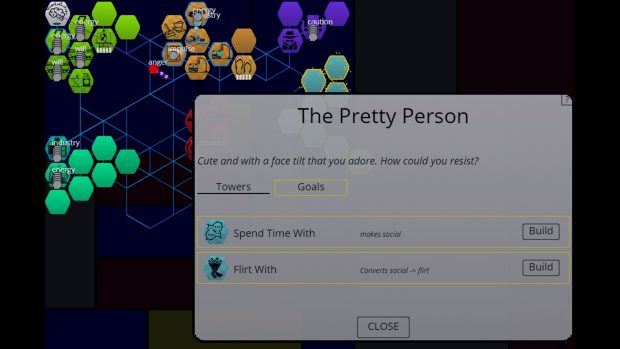

Here’s one story: I failed a date with someone I liked because my life was too much of a mess. Needing to pay my rent, I used my limited ability to travel on taking a job as a cab driver to earn money rather than on investing it into my date. And then anxieties caused by how late I was paying my rent overwhelmed me and the date timer ran out and there I was, alone again in the city.

There are many more stories in the first of The Quiet Sleep’s three scenarios. Most naturally bubble up from the natural flows of resources from one part of your life to another. Some, though, are the result of the specific tale its maker, Why Not Games, aka Nikhil Murthy, wants to tell, which interleaves the business of living with the experience of being a stranger in a strange land.

The scenario, which is eponymously named, begins with Adulthood, the name given to an area of bright green hexes at the top left of the screen. On these hexes you ‘build’ concepts relating to your character's life, first an Energy Spring, which generates a resource called Energy, and a Will Mine, which creates Will. You can then channel your energy and will into building Do Chores, which creates a resource called Chore, whereupon a new set of orange hexes called City appears.

If you read the flavour text for the City hexes, you’ll work out that you’ve moved far from home, and as you direct your will and energy into building hexes there you'll start establishing your place in this new city. On a more abstract level, though, you're kind of playing The Settlers, building structures and watching resources flowing from one to another, unlocking new structures. Perhaps a little Opus Magnum, too.

“This game started because I was thinking about the mechanical overlap between a Settlers-style game and tower defence,” Murthy tells me. “They both have these roads, but in a Settlers game you want those roads to be smooth and in a tower defence game you want them to be windy. So there’s that mechanical tension there, and I took that and thought, what if I put that in your mind?”

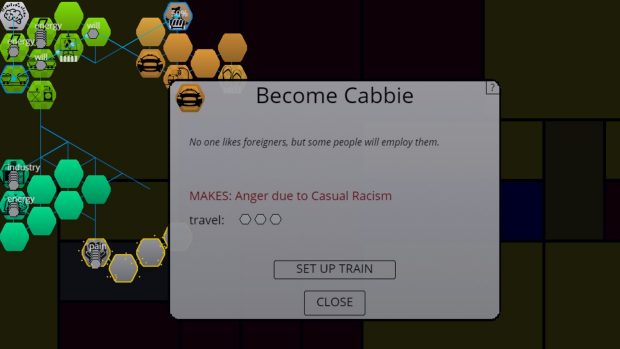

When you start a job to earn money, putting your Chore, Energy and other resources into cleaning or cab driving, new areas of hexes appear, such as Casual Racism, which generates Anger resources, a negative emotion (“No one likes foreigners, but some people will employ them”).

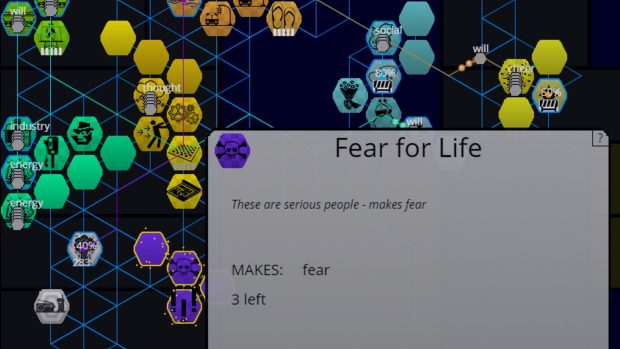

Many activities inadvertently create negative emotions, so cleaning creates frustration, while being away from home makes you sad, and they rapidly make their way towards the top left corner of the screen where a grey Self hex sits. If they reach it you’ll lose control, the game overlaying a simple minigame in which you have to keep a moving icon within a coloured strip while time continues and all your functions are disabled. And then comes a period of feeling ‘overwhelmed’, where you’ll feel no emotions at all.

To combat this, you need to strategically build defences on the hexes through which these emotions travel towards your Self. In the Adulthood area you can build Paint, which holds up to five charges that will absorb those emotions; in the City you can Walk, in the later Intelligent area you can Play Chess and, once you’re in a relationship, you can Vent To them in their area. But you’ll need to remember to keep them topped up, investing Energy in them as you manage an increasingly complex sprawl of other goals, some of which come with timers and many of which cause more emotions to rise.

“The thing I’m proudest of is that it tells you in a very systemic way that sometimes you can bite off more than you can chew, right?” says Murthy. “You’re trying four or five different things that produce tonnes of emotion and overwhelm your defence and cut straight to you. That’s something that’s true, right? People do this, running themselves ragged.”

And then new currents come into the story. New goals and emotions appear which suggest you’re not quite the person you thought you were. You begin spying on someone, which adds guilt and panic hexes. I won’t go any further in describing what happens, but the way it unfolds, revealing your personal reactions to what happens (my attempts often completely unravelled other areas of my life), is fascinating.

Also fascinating is Murthy’s inspiration for the culmination for the story, which is oblique enough that it won’t spoil anything. He was born in the US but grew up in India, and moved back to the US to go to college and take a job at a mobile games studio. He’d prototyped a new multiplayer game which the studio liked, but when the studio decided to push it into production he wasn’t given the role of leading it. Murthy understands; he was 24 and he says he’s not the easiest person to work with in some ways. But as he saw the game go in directions he didn’t like, he decided to leave the company.

“That game had been the biggest part of me for two years,” he says. “There was this hole; I’d walk to the grocery store and think about the game and I had to tell myself that there’s no point in thinking about it any more.” He moved back to India, and The Quiet Sleep is the first game he’s made since. “This game is about that hole.”

The other two stories expand on the ideas explored in the first. Songcraft is based around using the emotions which appear when you carry out activities to add inspiration to music. And in Evocations you conduct a relationship with an AI, attempting to make it feel emotion for you. “It’s a toxic story,” Murthy says.

The Quiet Sleep surprisingly has no sandbox or Rogue-like mode in which you play a life freely; in that sense, the potential of its core design feels undeveloped, just like its visuals. But Murthy never saw the game in that way. He wanted to tell these three stories, and as much as he understands its value, making the art prettier doesn’t creatively appeal to him.

“I wanted to make game that didn't feel like anything else,” he says. “There are bits and pieces of a bunch of other games in it, but I think the whole is very individual. And that meant I wanted to focus on the stuff that feels unique, that I didn’t feel that would be the visuals. This was very much a self-indulgent game.”

And yeah, that feels pretty appropriate for a game that captures messy human experience so vividly.

The Quiet Sleep is out now for Windows and MacOSX via Steam and Itch for £4/$5/€5.